Premium Only Content

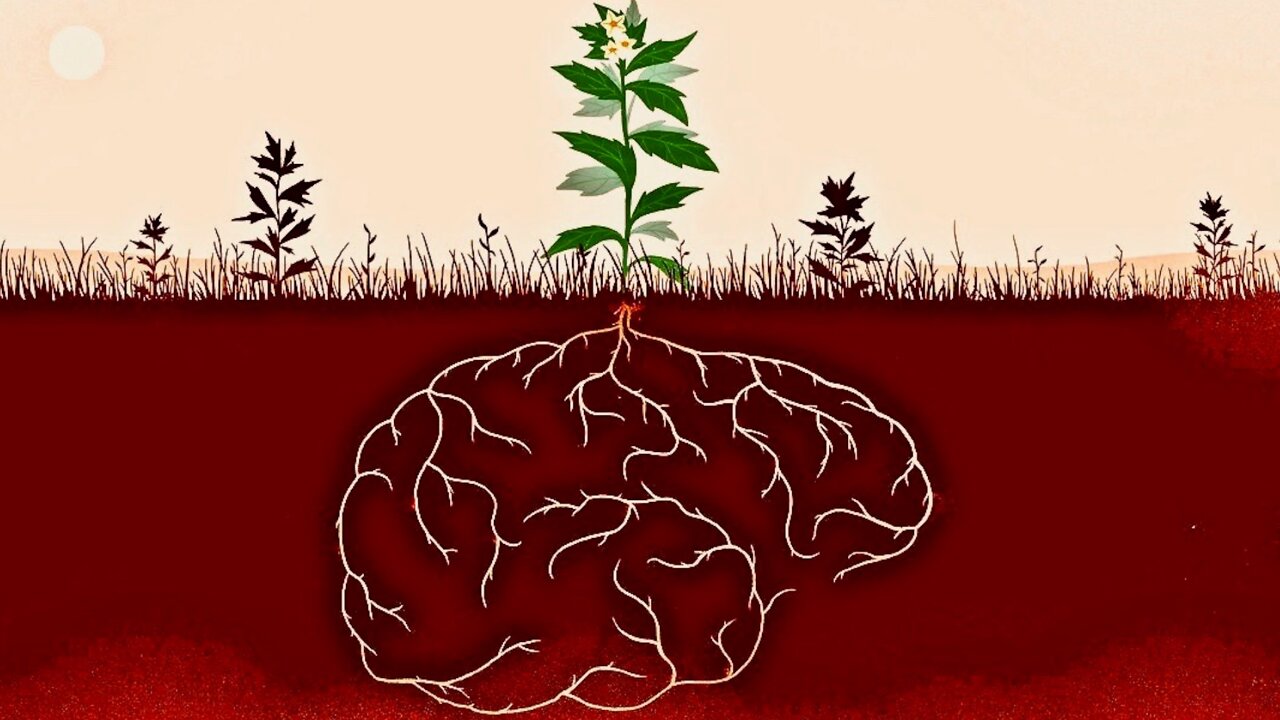

Plants Have Memory - Proven By Researchers

There's an eye-popping paper by Monica Gagliano, associate professor of biology at the University of Western Australia. She’s got a plant that not only “remembered” what happened to it but stored that memory for almost a month. The plant: Mimosa pudica leaves fold in after they are touched. The Sensitive plant, shame plant (Mimosa pudica), flower and leaf, leaves sensitiv, leaflets folded after touching.

Gardeners call Mimosa pudica “the sensitive plant,” because if you touch it even lightly or drop it or disturb it, within seconds it folds its teeny leaves into what looks like a frightened or defensive curl. It’s fun to watch it get all shy.

OK, so it’s highly sensitive. Knowing this, here’s what Gagliano did: She got a bunch of Mimosa pudicas, put them in pots, then loaded each one onto a special plant-dropping device using a sliding steel rail that worked like this:

Each potted plant was dropped roughly six inches, not once, but 60 times in a row at five-second intervals. The plants would glide into a soft, cushiony foam that prevented bouncing. The drop was sufficiently speedy to alarm the plant and cause its teeny leaves to fold into a defensive curl.

To “Eeek!” or Not to “Eeek!”

Six inches, however, is too short a distance to do harm, so what Gagliano wondered was: If she dropped 56 plants 60 times each, would these plants eventually realize nothing terrible was going to happen? Would any of them stop curling?

Or, to put it another way: Could a plant use memory to change its behavior?

To find out, she kept going with her experiment. And, as she writes in her paper, fairly quickly “observed that some individuals did not close their leaves fully when dropped.” In other words, plants seemed to figure out that falling this way wasn’t going to hurt, so more and more of them stopped protecting themselves—until, as she later told a room full of scientists, “By the end, they were completely open … They couldn’t care less anymore.”

Is this evidence of remembering, or is it something else? Maybe, skeptics suggested, all we’re seeing is a bunch of exhausted plants. Curling is work. It takes energy. After 60 drops, these plants may simply be pooped out—that’s why they don’t trigger their defenses. But Gagliano, anticipating this question, took some of those “tired” plants, put them in a shaker, shook them, and instantly they curled up again. “Oh, this is something new,” she imagined them saying, something that hasn’t happened before. That sense of a “before,” she said, is the best explanation for the plants’ change in behavior. They didn’t curl up again because “before” they’d learned there was no need. And they remembered.

A week later—after the shakings—she resumed her drops, and still the plants failed to get alarmed. Their leaves stayed open. She did it again, week after week, and after 28 days, these plants still “remembered” what they’d learned. That’s a long time to store a memory. Bees, she noted, forget what they’ve discovered in a couple of days.

But Without a Brain, How Do They Do It?

“Plants may lack brains,” Gagliano says in her paper, “but they do possess a sophisticated … signaling network.” Could there be some chemical or hormonal “unifying mechanism” that supports memory in plants? It wouldn’t be like an animal brain. It would be radically different, a distributed intelligence, organized in some way we don’t yet understand. But Gagliano thinks Mimosa pudica is challenging us to find out.

Michael Pollan, writing in the New Yorker, hung out with Gagliano last year, went with her to a science meeting, and vividly describes how she was roundly dismissed by many biologists, who bridle at the idea that any plant could be “intelligent.” Plants, they insist, are mainly genetic robots—they can’t learn from experience or change behavior. To say they can “generates strong feelings,” Pollan writes, “perhaps because it smudges the sharp line separating the animal kingdom from the plant kingdom.”

Plants have always been the bronze medalists, one step down from the animals, two steps down from us, the golden ones. By giving plants animal-like talents, Gagliano is mucking up the hierarchies, challenging the order of things.

We like to think because we have such big brains, we’re exceptional. Our trillions of neurons are keys to memory, feelings, consciousness. Brainless creatures by definition can’t do what we do—so of course, plants can’t “remember.”

But Gagliano says maybe they can.

Music: From Scales to Feathers by Dhruva Aliman

Amazon- https://amzn.to/2Mgr7pg

https://music.apple.com/us/artist/dhruva-aliman/363563637

https://dhruvaaliman.bandcamp.com/album/the-wolf-and-the-river

http://www.dhruvaaliman.com/

Spotify - https://open.spotify.com/artist/5XiFCr9iBKE6Cupltgnlet

-

2:05

2:05

Knowledge Land

17 days agoScientists revive dire wolf species from ‘Game of Thrones’ in world’s first known ‘de-extinction’

451 -

2:17

2:17

Groshlawn

3 years agoLandscaping Design Build Hagerstown MD Contractor Proven Winner Plants

39 -

0:53

0:53

KERO

3 years agoResearchers: Social media may have negative influence on healthy eating

101 -

0:37

0:37

Canopy Gardens Greenhouse

3 years agoPollinating Tomato Plants

55 -

1:10:17

1:10:17

Sarah Westall

8 hours agoWorld Leaders Increasingly Display Panic Behavior as Economic Change Accelerates w/ Andy Schectman

72.7K15 -

59:54

59:54

Motherland Casino

5 hours ago $1.55 earnedScar x Ayanna

27.9K5 -

41:57

41:57

BonginoReport

11 hours agoProtecting Kids From WOKE Ideology in School (Ep. 35) - Nightly Scroll with Hayley Caronia -04/25/25

118K50 -

LIVE

LIVE

SpartakusLIVE

8 hours agoFriday Night HYPE w/ #1 All-American Solo NUKE Hero

143 watching -

1:15:07

1:15:07

Kim Iversen

1 day agoThe Left Is Dead — What And Who Will Rise From the Ashes?

103K79 -

2:06:17

2:06:17

Joker Effect

6 hours agoYOU DON'T UNDERSTAND FREEDOM OF SPEECH IF THIS MAKES YOU MAD!

14.6K1