Premium Only Content

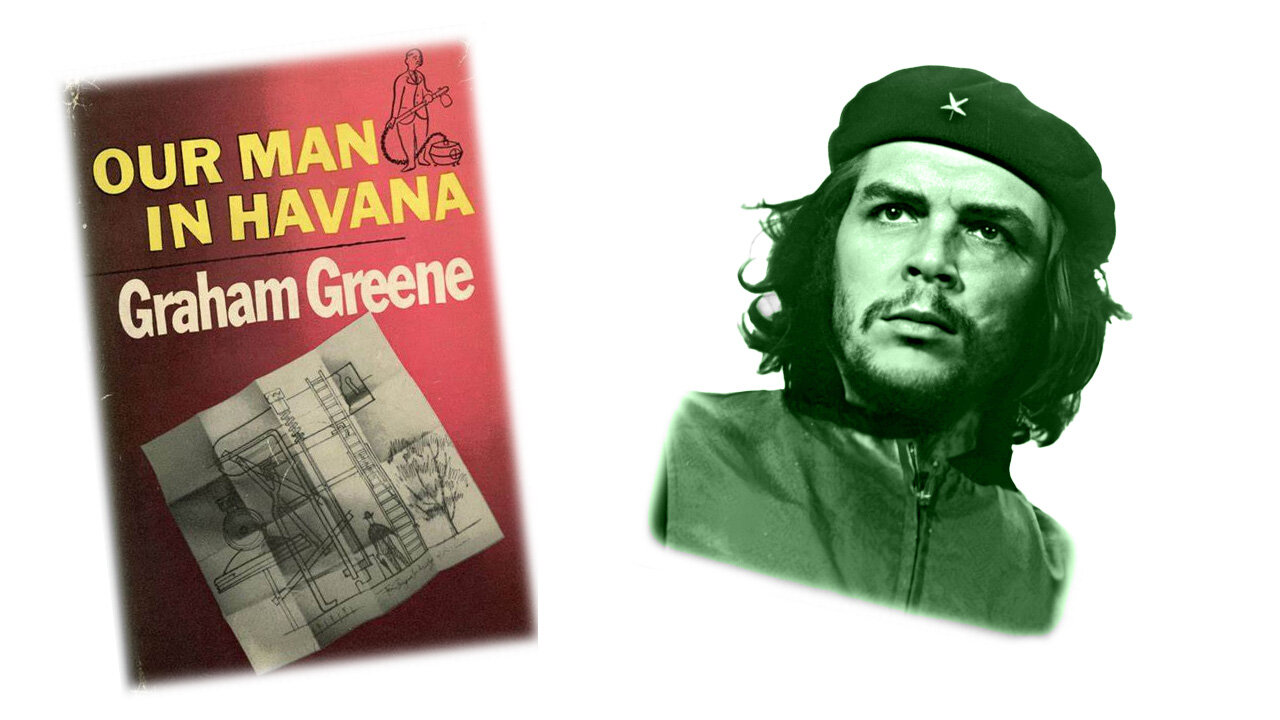

'Our Man in Havana' (1958) by Graham Greene

Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana (1958) is a satirical novel that blends humor with a biting critique of Cold War intelligence practices. Set in 1950s Cuba, just before the revolution, the novel follows James Wormold, a British vacuum cleaner salesman who is reluctantly drawn into the world of espionage. Through Wormold’s accidental career as a secret agent, Greene exposes the absurdity, incompetence, and moral ambiguity of the intelligence services, crafting a narrative that is both darkly comic and deeply reflective.

The story begins with James Wormold living a quiet and uneventful life in Havana, where he runs a small shop selling vacuum cleaners. His primary concern is providing for his teenage daughter, Milly, who has expensive tastes and dreams of owning a horse. Wormold, though a modest man, indulges Milly’s whims despite his financial limitations. His mundane existence is disrupted when he is approached by Hawthorne, a representative of the British Secret Service, who recruits him as their agent in Cuba. Though Wormold is bewildered by the offer, he accepts it not out of patriotism or interest in espionage, but as a practical solution to his financial troubles.

Faced with the challenge of producing intelligence without any real contacts or knowledge, Wormold turns to fabrication. He invents an entire network of imaginary agents and submits false reports to London. To maintain the illusion, he draws detailed blueprints of supposed Cuban military installations—designs which are, in fact, based on vacuum cleaner parts. His fictitious reports are not only accepted but celebrated by his superiors, who view him as a valuable and productive asset. This absurd scenario highlights Greene’s satirical portrayal of intelligence agencies as organizations more concerned with the appearance of efficiency than with the truth.

What begins as a harmless con soon takes on a more dangerous dimension. Wormold’s fabricated intelligence gains the attention of rival intelligence agencies, including Cuban authorities. The consequences of his deception become painfully real as individuals he names as agents begin to suffer mysterious accidents and disappearances. The absurdity of his lies is replaced by genuine peril as Wormold himself becomes a target for assassination. This escalation from comic farce to life-threatening danger underscores one of the novel’s central themes: the fine line between humor and tragedy.

The arrival of Beatrice, a secretary sent from London to assist Wormold, further complicates his deception. Unlike Wormold, Beatrice is idealistic and committed to her work, which forces Wormold to maintain his fabrications even as the consequences spiral beyond his control. When a real enemy agent attempts to kill him, Wormold is forced to confront the moral weight of his actions. Although he ultimately survives and exposes the assassin, the experience forces him to reckon with the ethical implications of his lies.

Despite the chaos and danger caused by his deceptions, Wormold is not punished. Instead, the British intelligence bureaucracy chooses to reward him with a comfortable position and even offers him a place on the Queen’s honors list. This conclusion reinforces Greene’s critique of institutional incompetence and the self-preserving nature of bureaucracies, which prioritize appearances over accountability. By allowing Wormold to escape the consequences of his actions, the system reveals itself to be less concerned with truth than with maintaining its own image.

A central theme of Our Man in Havana is the moral ambiguity inherent in espionage. Wormold’s journey from an ordinary salesman to a reluctant participant in life-and-death situations illustrates how small lies can escalate into profound ethical dilemmas. Initially viewing his role as a harmless way to make money, Wormold comes to realize that his falsehoods have real-world consequences, including the loss of innocent lives. Greene uses Wormold’s moral evolution to question the ethics of intelligence work and the human cost of political gamesmanship.

The novel also functions as a satire of the Cold War intelligence apparatus. Greene mocks the paranoia and incompetence of Western intelligence agencies, which are depicted as more interested in bureaucratic processes and maintaining appearances than in uncovering truth. The ease with which Wormold fools his superiors reflects a larger critique of a system that values information—whether true or not—over critical thinking and genuine understanding. The absurdity of this system is further emphasized by the fact that Wormold’s most outlandish inventions are not only believed but rewarded.

Through its blend of humor and suspense, Our Man in Havana provides both an entertaining narrative and a profound commentary on power, deception, and the absurdity of Cold War politics. Greene’s portrayal of Wormold as an everyman figure, caught between personal necessity and institutional absurdity, emphasizes the novel’s central message: that the world of espionage, for all its secrecy and seriousness, is often governed by incompetence and blind faith in appearances. The novel’s enduring relevance lies in its exploration of how systems of power can be both dangerous and deeply ridiculous, a theme that resonates far beyond the specific historical context of 1950s Cuba.

In the end, Our Man in Havana is not just a comic farce but a serious exploration of moral responsibility in a world where truth is often secondary to political convenience. Greene’s sharp wit and keen insight into human nature make the novel a timeless reflection on the consequences of deception and the absurdities of institutional power. Through the story of a humble vacuum cleaner salesman turned accidental spy, Greene crafts a narrative that is as thought-provoking as it is entertaining.

-

18:37

18:37

Clownfish TV

2 hours agoThe Oscars Just EMBARASSED Disney and Emilia Pérez...

26.2K7 -

56:28

56:28

Glenn Greenwald

4 hours agoDocumentary Exposing Repression in West Bank Wins at Oscars; Free Speech Lawyer Jenin Younes on Double Standards for Israel's Critics | SYSTEM UPDATE #416

65K35 -

1:03:34

1:03:34

Donald Trump Jr.

6 hours agoZelensky Overplays His Hand, More Trump Wins, Plus Interview with Joe Bastardi | Triggered Ep.221

128K87 -

1:13:16

1:13:16

We Like Shooting

15 hours ago $0.04 earnedDouble Tap 399 (Gun Podcast)

21.1K -

1:00:20

1:00:20

The Tom Renz Show

22 hours agoTrump Schools Zelensky, The Epstein Files FAIL, & What RFK Will Mean for Cancer

28.7K13 -

42:47

42:47

Kimberly Guilfoyle

8 hours agoThe Trump effect: More Major Investment, Plus America First at Home & Abroad. Live w/Ned Ryun & Brett Tolman | Ep. 201

97.1K34 -

1:29:23

1:29:23

Redacted News

7 hours agoWW3 ALERT! Europe pushes for war against Russia as Trump pushes peace and cutting off Zelensky

138K258 -

57:56

57:56

Candace Show Podcast

10 hours agoHarvey Speaks: The Project Runway Production | Ep 1

136K80 -

56:31

56:31

LFA TV

1 day agoEurope’s Relationship With America Is Over | TRUMPET DAILY 3.3.25 7PM

35.2K6 -

2:04:45

2:04:45

Quite Frankly

8 hours ago"European Deth Pact, Blackout Data Breach, Epstein" ft. Jason Bermas 3/3/25

36.7K13