Premium Only Content

The Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI (2002)

In 1896, the National Bureau of Criminal Identification was founded, providing agencies across the country with information to identify known criminals. The 1901 assassination of President William McKinley created a perception that the United States was under threat from anarchists. The Departments of Justice and Labor had been keeping records on anarchists for years, but President Theodore Roosevelt wanted more power to monitor them.[14][page needed]

The Justice Department had been tasked with the regulation of interstate commerce since 1887, though it lacked the staff to do so. It had made little effort to relieve its staff shortage until the Oregon land fraud scandal at the turn of the 20th century. President Roosevelt instructed Attorney General Charles Bonaparte to organize an autonomous investigative service that would report only to the Attorney General.[15]

Bonaparte reached out to other agencies, including the U.S. Secret Service, for personnel, investigators in particular. On May 27, 1908, Congress forbade this use of Treasury employees by the Justice Department, citing fears that the new agency would serve as a secret police department.[16] Again at Roosevelt's urging, Bonaparte moved to organize a formal Bureau of Investigation, which would then have its own staff of special agents.[14][page needed]

Creation of BOI

The Bureau of Investigation (BOI) was created on July 26, 1908.[17] Attorney General Bonaparte, using Department of Justice expense funds,[14] hired thirty-four people, including some veterans of the Secret Service,[18][19] to work for a new investigative agency. Its first "chief" (the title is now "director") was Stanley Finch. Bonaparte notified the Congress of these actions in December 1908.[14]

The bureau's first official task was visiting and making surveys of the houses of prostitution in preparation for enforcing the "White Slave Traffic Act" or Mann Act, passed on June 25, 1910. In 1932, the bureau was renamed the United States Bureau of Investigation.

Creation of FBI

The following year, 1933, the BOI was linked to the Bureau of Prohibition and rechristened the Division of Investigation (DOI); it became an independent service within the Department of Justice in 1935.[18] In the same year, its name was officially changed from the Division of Investigation to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

J. Edgar Hoover as FBI director

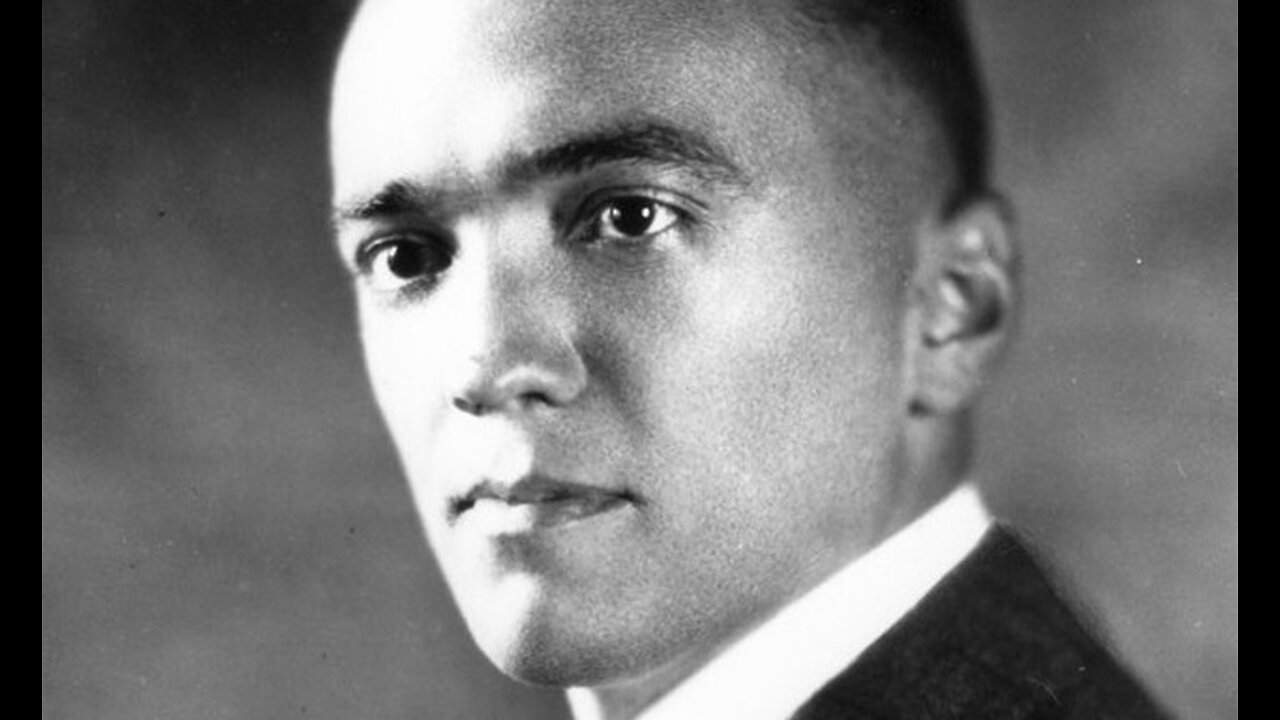

J. Edgar Hoover, FBI director from 1924 to 1972

J. Edgar Hoover served as FBI director from 1924 to 1972, a combined 48 years with the BOI, DOI, and FBI. He was chiefly responsible for creating the Scientific Crime Detection Laboratory, or the FBI Laboratory, which officially opened in 1932, as part of his work to professionalize investigations by the government. Hoover was substantially involved in most major cases and projects that the FBI handled during his tenure. But as detailed below, his tenure as Bureau director proved to be highly controversial, especially in its later years. After Hoover's death, Congress passed legislation that limited the tenure of future FBI directors to ten years.

Early homicide investigations of the new agency included the Osage Indian murders. During the "War on Crime" of the 1930s, FBI agents apprehended or killed a number of notorious criminals who committed kidnappings, bank robberies, and murders throughout the nation, including John Dillinger, "Baby Face" Nelson, Kate "Ma" Barker, Alvin "Creepy" Karpis, and George "Machine Gun" Kelly.

Other activities of its early decades focused on the scope and influence of the white supremacist group Ku Klux Klan, a group with which the FBI was evidenced to be working in the Viola Liuzzo lynching case. Earlier, through the work of Edwin Atherton, the BOI claimed to have successfully apprehended an entire army of Mexican neo-revolutionaries under the leadership of General Enrique Estrada in the mid-1920s, east of San Diego, California.

Hoover began using wiretapping in the 1920s during Prohibition to arrest bootleggers.[20] In the 1927 case Olmstead v. United States, in which a bootlegger was caught through telephone tapping, the United States Supreme Court ruled that FBI wiretaps did not violate the Fourth Amendment as unlawful search and seizure, as long as the FBI did not break into a person's home to complete the tapping.[20] After Prohibition's repeal, Congress passed the Communications Act of 1934, which outlawed non-consensual phone tapping, but did allow bugging.[20] In the 1939 case Nardone v. United States, the court ruled that due to the 1934 law, evidence the FBI obtained by phone tapping was inadmissible in court.[20] After Katz v. United States (1967) overturned Olmstead, Congress passed the Omnibus Crime Control Act, allowing public authorities to tap telephones during investigations, as long as they obtained warrants beforehand.[20]

National security

Beginning in the 1940s and continuing into the 1970s, the bureau investigated cases of espionage against the United States and its allies. Eight Nazi agents who had planned sabotage operations against American targets were arrested, and six were executed (Ex parte Quirin) under their sentences. Also during this time, a joint US/UK code-breaking effort called "The Venona Project"—with which the FBI was heavily involved—broke Soviet diplomatic and intelligence communications codes, allowing the US and British governments to read Soviet communications. This effort confirmed the existence of Americans working in the United States for Soviet intelligence.[21] Hoover was administering this project, but he failed to notify the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of it until 1952. Another notable case was the arrest of Soviet spy Rudolf Abel in 1957.[22] The discovery of Soviet spies operating in the US motivated Hoover to pursue his longstanding concern with the threat he perceived from the American Left.

Japanese American internment

In 1939, the Bureau began compiling a custodial detention list with the names of those who would be taken into custody in the event of war with Axis nations. The majority of the names on the list belonged to Issei community leaders, as the FBI investigation built on an existing Naval Intelligence index that had focused on Japanese Americans in Hawaii and the West Coast, but many German and Italian nationals also found their way onto the FBI Index list.[23] Robert Shivers, head of the Honolulu office, obtained permission from Hoover to start detaining those on the list on December 7, 1941, while bombs were still falling over Pearl Harbor.[24][better source needed] Mass arrests and searches of homes, in most cases conducted without warrants, began a few hours after the attack, and over the next several weeks more than 5,500 Issei men were taken into FBI custody.[25]

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. FBI Director Hoover opposed the subsequent mass removal and confinement of Japanese Americans authorized under Executive Order 9066, but Roosevelt prevailed.[26] The vast majority went along with the subsequent exclusion orders, but in a handful of cases where Japanese Americans refused to obey the new military regulations, FBI agents handled their arrests.[24] The Bureau continued surveillance on Japanese Americans throughout the war, conducting background checks on applicants for resettlement outside camp, and entering the camps, usually without the permission of War Relocation Authority officials, and grooming informants to monitor dissidents and "troublemakers". After the war, the FBI was assigned to protect returning Japanese Americans from attacks by hostile white communities.[24]

Sex deviates program

According to Douglas M. Charles, the FBI's "sex deviates" program began on April 10, 1950, when J. Edgar Hoover forwarded to the White House, to the U.S. Civil Service Commission, and to branches of the armed services a list of 393 alleged federal employees who had allegedly been arrested in Washington, D.C., since 1947, on charges of "sexual irregularities". On June 20, 1951, Hoover expanded the program by issuing a memo establishing a "uniform policy for the handling of the increasing number of reports and allegations concerning present and past employees of the United States Government who assertedly [sic] are sex deviates." The program was expanded to include non-government jobs. According to Athan Theoharis, "In 1951 he [Hoover] had unilaterally instituted a Sex Deviates program to purge alleged homosexuals from any position in the federal government, from the lowliest clerk to the more powerful position of White house aide." On May 27, 1953, Executive Order 10450 went into effect. The program was expanded further by this executive order by making all federal employment of homosexuals illegal. On July 8, 1953, the FBI forwarded to the U.S. Civil Service Commission information from the sex deviates program. Between 1977 and 1978, 300,000 pages in the sex deviates program, collected between 1930 and the mid-1970s, were destroyed by FBI officials.[27][28][29]

Civil rights movement

During the 1950s and 1960s, FBI officials became increasingly concerned about the influence of civil rights leaders, whom they believed either had communist ties or were unduly influenced by communists or "fellow travelers". In 1956, for example, Hoover sent an open letter denouncing Dr. T. R. M. Howard, a civil rights leader, surgeon, and wealthy entrepreneur in Mississippi who had criticized FBI inaction in solving recent murders of George W. Lee, Emmett Till, and other blacks in the South.[30] The FBI carried out controversial domestic surveillance in an operation it called the COINTELPRO, from "COunter-INTELligence PROgram".[31] It was to investigate and disrupt the activities of dissident political organizations within the United States, including both militant and non-violent organizations. Among its targets was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a leading civil rights organization whose clergy leadership included the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr..[32]

The "suicide letter",[33] mailed anonymously to King by the FBI

The FBI frequently investigated King. In the mid-1960s, King began to criticize the Bureau for giving insufficient attention to the use of terrorism by white supremacists. Hoover responded by publicly calling King the most "notorious liar" in the United States.[34] In his 1991 memoir, Washington Post journalist Carl Rowan asserted that the FBI had sent at least one anonymous letter to King encouraging him to commit suicide.[35] Historian Taylor Branch documents an anonymous November 1964 "suicide package" sent by the Bureau that combined a letter to the civil rights leader telling him "You are done. There is only one way out for you." with audio recordings of King's sexual indiscretions.[36]

In March 1971, the residential office of an FBI agent in Media, Pennsylvania was burgled by a group calling itself the Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI. Numerous files were taken and distributed to a range of newspapers, including The Harvard Crimson.[37] The files detailed the FBI's extensive COINTELPRO program, which included investigations into lives of ordinary citizens—including a black student group at a Pennsylvania military college and the daughter of Congressman Henry S. Reuss of Wisconsin.[37] The country was "jolted" by the revelations, which included assassinations of political activists, and the actions were denounced by members of the Congress, including House Majority Leader Hale Boggs.[37] The phones of some members of the Congress, including Boggs, had allegedly been tapped.[37]

Kennedy's assassination

When President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed, the jurisdiction fell to the local police departments until President Lyndon B. Johnson directed the FBI to take over the investigation.[38] To ensure clarity about the responsibility for investigation of homicides of federal officials, Congress passed a law in 1965 that included investigations of such deaths of federal officials, especially by homicide, within FBI jurisdiction.[39][40][41]

Organized crime

An FBI surveillance photograph of Joseph D. Pistone (aka Donnie Brasco), Benjamin "Lefty" Ruggiero and Edgar Robb (aka Tony Rossi), 1980s

In response to organized crime, on August 25, 1953, the FBI created the Top Hoodlum Program. The national office directed field offices to gather information on mobsters in their territories and to report it regularly to Washington for a centralized collection of intelligence on racketeers.[42] After the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, for RICO Act, took effect, the FBI began investigating the former Prohibition-organized groups, which had become fronts for crime in major cities and small towns. All the FBI work was done undercover and from within these organizations, using the provisions provided in the RICO Act. Gradually the agency dismantled many of the groups. Although Hoover initially denied the existence of a National Crime Syndicate in the United States, the Bureau later conducted operations against known organized crime syndicates and families, including those headed by Sam Giancana and John Gotti. The RICO Act is still used today for all organized crime and any individuals who may fall under the Act's provisions.

In 2003, a congressional committee called the FBI's organized crime informant program "one of the greatest failures in the history of federal law enforcement."[43] The FBI allowed four innocent men to be convicted of the March 1965 gangland murder of Edward "Teddy" Deegan in order to protect Vincent Flemmi, an FBI informant. Three of the men were sentenced to death (which was later reduced to life in prison), and the fourth defendant was sentenced to life in prison.[43] Two of the four men died in prison after serving almost 30 years, and two others were released after serving 32 and 36 years. In July 2007, U.S. District Judge Nancy Gertner in Boston found that the Bureau had helped convict the four men using false witness accounts given by mobster Joseph Barboza. The U.S. Government was ordered to pay $100 million in damages to the four defendants.[44]

Special FBI teams

FBI SWAT agents in a training exercise

In 1982, the FBI formed an elite unit[45] to help with problems that might arise at the 1984 Summer Olympics to be held in Los Angeles, particularly terrorism and major-crime. This was a result of the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, Germany, when terrorists murdered the Israeli athletes. Named the Hostage Rescue Team, or HRT, it acts as a dedicated FBI SWAT team dealing primarily with counter-terrorism scenarios. Unlike the special agents serving on local FBI SWAT teams, HRT does not conduct investigations. Instead, HRT focuses solely on additional tactical proficiency and capabilities. Also formed in 1984 was the Computer Analysis and Response Team, or CART.[46]

From the end of the 1980s to the early 1990s, the FBI reassigned more than 300 agents from foreign counter-intelligence duties to violent crime, and made violent crime the sixth national priority. With cuts to other well-established departments, and because terrorism was no longer considered a threat after the end of the Cold War,[46] the FBI assisted local and state police forces in tracking fugitives who had crossed state lines, which is a federal offense. The FBI Laboratory helped develop DNA testing, continuing its pioneering role in identification that began with its fingerprinting system in 1924.

Notable efforts in the 1990s

An FBI agent tags the cockpit voice recorder from EgyptAir Flight 990 on the deck of the USS Grapple (ARS 53) at the crash site on November 13, 1999.

On May 1, 1992, FBI SWAT and HRT personnel in Los Angeles County, California aided local officials in securing peace within the area during the 1992 Los Angeles riots. HRT operators, for instance, spent 10 days conducting vehicle-mounted patrols throughout Los Angeles, before returning to Virginia.[47]

Between 1993 and 1996, the FBI increased its counter-terrorism role following the first 1993 World Trade Center bombing in New York City, the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, and the arrest of the Unabomber in 1996. Technological innovation and the skills of FBI Laboratory analysts helped ensure that the three cases were successfully prosecuted.[48] However, Justice Department investigations into the FBI's roles in the Ruby Ridge and Waco incidents were found to have been obstructed by agents within the Bureau. During the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia, the FBI was criticized for its investigation of the Centennial Olympic Park bombing. It has settled a dispute with Richard Jewell, who was a private security guard at the venue, along with some media organizations,[49] in regard to the leaking of his name during the investigation; this had briefly led to his being wrongly suspected of the bombing.

After Congress passed the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA, 1994), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA, 1996), and the Economic Espionage Act (EEA, 1996), the FBI followed suit and underwent a technological upgrade in 1998, just as it did with its CART team in 1991. Computer Investigations and Infrastructure Threat Assessment Center (CITAC) and the National Infrastructure Protection Center (NIPC) were created to deal with the increase in Internet-related problems, such as computer viruses, worms, and other malicious programs that threatened U.S. operations. With these developments, the FBI increased its electronic surveillance in public safety and national security investigations, adapting to the telecommunications advancements that changed the nature of such problems.

September 11 attacks

September 11 attacks at the Pentagon

During the September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center, FBI agent Leonard W. Hatton Jr. was killed during the rescue effort while helping the rescue personnel evacuate the occupants of the South Tower, and he stayed when it collapsed. Within months after the attacks, FBI Director Robert Mueller, who had been sworn in a week before the attacks, called for a re-engineering of FBI structure and operations. He made countering every federal crime a top priority, including the prevention of terrorism, countering foreign intelligence operations, addressing cybersecurity threats, other high-tech crimes, protecting civil rights, combating public corruption, organized crime, white-collar crime, and major acts of violent crime.[50]

In February 2001, Robert Hanssen was caught selling information to the Russian government. It was later learned that Hanssen, who had reached a high position within the FBI, had been selling intelligence since as early as 1979. He pleaded guilty to espionage and received a life sentence in 2002, but the incident led many to question the security practices employed by the FBI. There was also a claim that Hanssen might have contributed information that led to the September 11, 2001, attacks.[51]

The 9/11 Commission's final report on July 22, 2004, stated that the FBI and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) were both partially to blame for not pursuing intelligence reports that could have prevented the September 11 attacks. In its most damning assessment, the report concluded that the country had "not been well served" by either agency and listed numerous recommendations for changes within the FBI.[52] While the FBI did accede to most of the recommendations, including oversight by the new director of National Intelligence, some former members of the 9/11 Commission publicly criticized the FBI in October 2005, claiming it was resisting any meaningful changes.[53]

On July 8, 2007, The Washington Post published excerpts from UCLA Professor Amy Zegart's book Spying Blind: The CIA, the FBI, and the Origins of 9/11.[54] The Post reported, from Zegart's book, that government documents showed that both the CIA and the FBI had missed 23 potential chances to disrupt the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The primary reasons for the failures included: agency cultures resistant to change and new ideas; inappropriate incentives for promotion; and a lack of cooperation between the FBI, CIA, and the rest of the United States Intelligence Community. The book blamed the FBI's decentralized structure, which prevented effective communication and cooperation among different FBI offices. The book suggested that the FBI had not evolved into an effective counter-terrorism or counter-intelligence agency, due in large part to deeply ingrained agency cultural resistance to change. For example, FBI personnel practices continued to treat all staff other than special agents as support staff, classifying intelligence analysts alongside the FBI's auto mechanics and janitors.[55]

-

31:00

31:00

The Memory Hole

21 days agoThe Perils of a Life of Dirty Tricks in the CIA (1978)

821 -

34:12

34:12

inspirePlay

1 day ago $5.45 earned🏆 The Grid Championship 2024 – Cass Meyer vs. Kelly Rudney | Epic Battle for Long Drive Glory!

80.3K8 -

17:50

17:50

BlackDiamondGunsandGear

13 hours ago $2.61 earnedTeach Me How to Build an AR-15

54.9K6 -

9:11

9:11

Space Ice

1 day agoFatman - Greatest Santa Claus Fighting Hitmen Movie Of Mel Gibson's Career - Best Movie Ever

114K47 -

42:38

42:38

Brewzle

1 day agoI Spent Too Much Money Bourbon Hunting In Kentucky

76.6K12 -

1:15:30

1:15:30

World Nomac

22 hours agoMY FIRST DAY BACK in Manila Philippines 🇵🇭

59.1K9 -

13:19

13:19

Dr David Jockers

1 day ago $11.27 earned5 Dangerous Food Ingredients That Drive Inflammation

78.3K17 -

1:05:13

1:05:13

FamilyFriendlyGaming

1 day ago $15.85 earnedCat Quest III Episode 8

129K3 -

10:39

10:39

Cooking with Gruel

2 days agoMastering a Succulent London Broil

83.3K5 -

22:15

22:15

barstoolsports

1 day agoWhite Elephant Sends Barstool Office into Chaos | VIVA TV

58.8K1