Premium Only Content

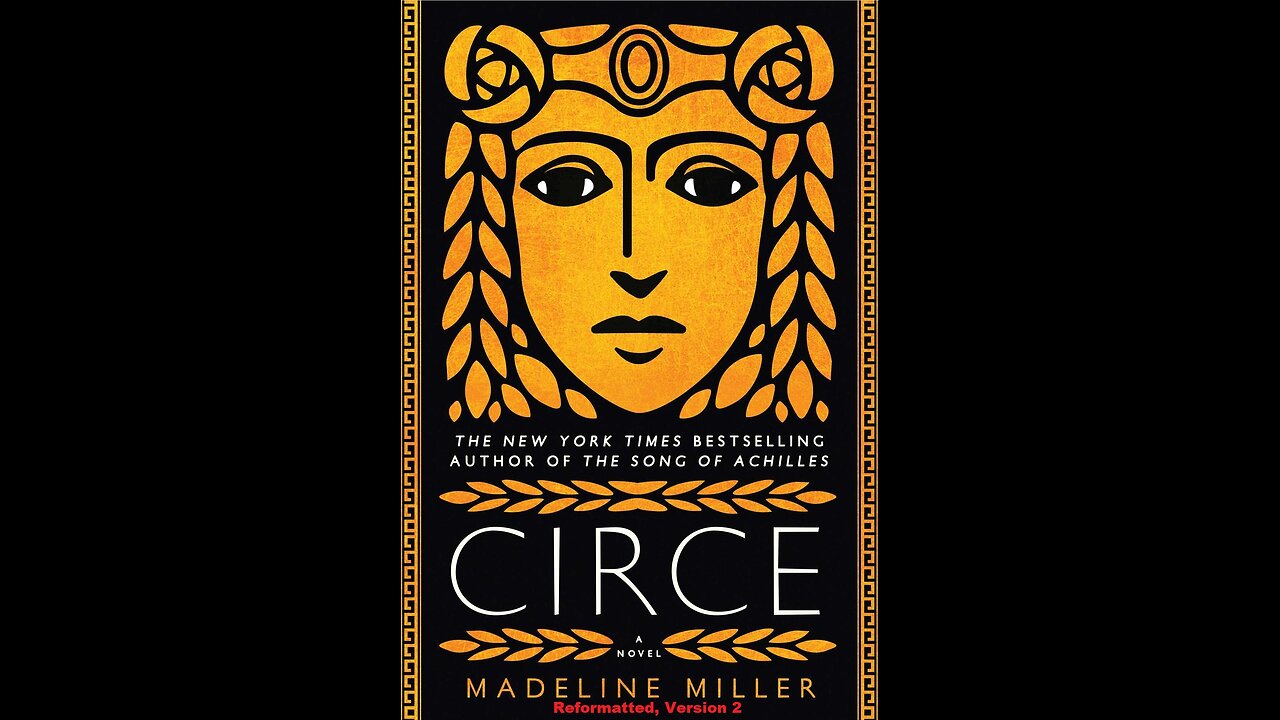

Circe. Copyright 2018 by Madeline Miller. A Puke(TM) Audiobook

Circe.

Copyright 2018 by Madeline Miller.

Reformatted for Machine Speech, PukeOnAPlate2024.

Version 2

Chapter One.

When I was born, the name for what I was did not exist. They called me nymph, assuming I would be like my mother and aunts and thousand cousins. Least of the lesser goddesses, our powers were so modest they could scarcely ensure our eternities. We spoke to fish and nurtured flowers, coaxed drops from the clouds or salt from the waves. That word, nymph, paced out the length and breadth of our futures. In our language, it means not just goddess, but bride.

My mother was one of them, a naiad, guardian of fountains and streams. She caught my father’s eye when he came to visit the halls of her own father, Oceanos. Helios and Oceanos were often at each other’s tables in those days. They were cousins, and equal in age, though they did not look it. My father glowed bright as just-forged bronze, while Oceanos had been born with rheumy eyes and a white beard to his lap. Yet they were both Titans, and preferred each other’s company to those new-squeaking gods upon Olympus who had not seen the making of the world.

Oceanos’ palace was a great wonder, set deep in the earth’s rock. Its high-arched halls were gilded, the stone floors smoothed by centuries of divine feet. Through every room ran the faint sound of Oceanos’ river, source of the world’s fresh waters, so dark you could not tell where it ended and the rock-bed began. On its banks grew grass and soft gray flowers, and also the unnumbered children of Oceanos, naiads and nymphs and river-gods. Otter-sleek, laughing, their faces bright against the dusky air, they passed golden goblets among themselves and wrestled, playing games of love. In their midst, outshining all that lily beauty, sat my mother.

Her hair was a warm brown, each strand so lustrous it seemed lit from within. She would have felt my father’s gaze, hot as gusts from a bonfire. I see her arrange her dress so it drapes just so over her shoulders. I see her dab her fingers, glinting, in the water. I have seen her do a thousand such tricks a thousand times. My father always fell for them. He believed the world’s natural order was to please him.

“Who is that?” my father said to Oceanos.

Oceanos had many golden-eyed grandchildren from my father already, and was glad to think of more. “My daughter Perse. She is yours if you want her.”

The next day, my father found her by her fountain-pool in the upper world. It was a beautiful place, crowded with fat-headed narcissus, woven over with oak branches. There was no muck, no slimy frogs, only clean, round stones giving way to grass. Even my father, who cared nothing for the subtleties of nymph arts, admired it.

My mother knew he was coming. Frail she was, but crafty, with a mind like a spike-toothed eel. She saw where the path to power lay for such as her, and it was not in bastards and riverbank tumbles. When he stood before her, arrayed in his glory, she laughed at him. Lie with you? Why should I?

My father, of course, might have taken what he wanted. But Helios flattered himself that all women went eager to his bed, slave girls and divinities alike. His altars smoked with the proof, offerings from big-bellied mothers and happy by-blows.

“It is marriage,” she said to him, “or nothing. And if it is marriage, be sure: you may have what girls you like in the field, but you will bring none home, for only I will hold sway in your halls.”

Conditions, constrainment. These were novelties to my father, and gods love nothing more than novelty. “A bargain,” he said, and gave her a necklace to seal it, one of his own making, strung with beads of rarest amber. Later, when I was born, he gave her a second strand, and another for each of my three siblings. I do not know which she treasured more: the luminous beads themselves or the envy of her sisters when she wore them. I think she would have gone right on collecting them into eternity until they hung from her neck like a yoke on an ox if the high gods had not stopped her. By then they had learned what the four of us were. You may have other children, they told her, only not with him. But other husbands did not give amber beads. It was the only time I ever saw her weep.

At my birth, an aunt, I will spare you her name because my tale is full of aunts, washed and wrapped me. Another tended to my mother, painting the red back on her lips, brushing her hair with ivory combs. A third went to the door to admit my father.

“A girl,” my mother said to him, wrinkling her nose.

But my father did not mind his daughters, who were sweet-tempered and golden as the first press of olives. Men and gods paid dearly for the chance to breed from their blood, and my father’s treasury was said to rival that of the king of the gods himself. He placed his hand on my head in blessing.

“She will make a fair match,” he said.

“How fair?” my mother wanted to know. This might be consolation, if I could be traded for something better.

My father considered, fingering the wisps of my hair, examining my eyes and the cut of my cheeks.

“A prince, I think.”

“A prince?” my mother said. “You do not mean a mortal?”

The revulsion was plain on her face. Once when I was young I asked what mortals looked like. My father said, “You may say they are shaped like us, but only as the worm is shaped like the whale.”

My mother had been simpler: like savage bags of rotten flesh.

“Surely she will marry a son of Zeus,” my mother insisted. She had already begun imagining herself at feasts upon Olympus, sitting at Queen Hera’s right hand.

“No. Her hair is streaked like a lynx. And her chin. There is a sharpness to it that is less than pleasing.”

My mother did not argue further. Like everyone, she knew the stories of Helios’ temper when he was crossed. However gold he shines, do not forget his fire.

She stood. Her belly was gone, her waist reknitted, her cheeks fresh and virgin-rosy. All our kind recover quickly, but she was faster still, one of the daughters of Oceanos, who shoot their babes like roe.

“Come,” she said. “Let us make a better one.”

I grew quickly. My infancy was the work of hours, my toddlerhood a few moments beyond that. An aunt stayed on hoping to curry favor with my mother and named me Hawk, Circe, for my yellow eyes, and the strange, thin sound of my crying. But when she realized that my mother no more noticed her service than the ground at her feet, she vanished.

“Mother,” I said, “Aunt is gone.”

My mother didn’t answer. My father had already departed for his chariot in the sky, and she was winding her hair with flowers, preparing to leave through the secret ways of water, to join her sisters on their grassy riverbanks. I might have followed, but then I would have had to sit all day at my aunts’ feet while they gossiped of things I did not care for and could not understand. So I stayed.

My father’s halls were dark and silent. His palace was a neighbor to Oceanos’, buried in the earth’s rock, and its walls were made of polished obsidian. Why not? They could have been anything in the world, blood-red marble from Egypt or balsam from Araby, my father had only to wish it so. But he liked the way the obsidian reflected his light, the way its slick surfaces caught fire as he passed. Of course, he did not consider how black it would be when he was gone. My father has never been able to imagine the world without himself in it.

I could do what I liked at those times: light a torch and run to see the dark flames follow me. Lie on the smooth earth floor and wear small holes in its surface with my fingers. There were no grubs or worms, though I didn’t know to miss them. Nothing lived in those halls, except for us.

When my father returned at night, the ground rippled like the flank of a horse, and the holes I had made smoothed themselves over. A moment later my mother returned, smelling of flowers. She ran to greet him, and he let her hang from his neck, accepted wine, went to his great silver chair. I followed at his heels. Welcome home, Father, welcome home.

While he drank his wine, he played draughts. No one was allowed to play with him. He placed the stone counters, spun the board, and placed them again. My mother drenched her voice in honey. “Will you not come to bed, my love?” She turned before him slowly, showing the lushness of her figure as if she were roasting on a spit. Most often he would leave his game then, but sometimes he did not, and those were my favorite times, for my mother would go, slamming the myrrh-wood door behind her.

At my father’s feet, the whole world was made of gold. The light came from everywhere at once, his yellow skin, his lambent eyes, the bronze flashing of his hair. His flesh was hot as a brazier, and I pressed as close as he would let me, like a lizard to noonday rocks. My aunt had said that some of the lesser gods could scarcely bear to look at him, but I was his daughter and blood, and I stared at his face so long that when I looked away it was pressed upon my vision still, glowing from the floors, the shining walls and inlaid tables, even my own skin.

“What would happen,” I said, “if a mortal saw you in your fullest glory?”

“He would be burned to ash in a second.”

“What if a mortal saw me?”

My father smiled. I listened to the draught pieces moving, the familiar rasp of marble against wood. “The mortal would count himself fortunate.”

“I would not burn him?”

“Of course not,” he said.

“But my eyes are like yours.”

“No,” he said. “Look.” His gaze fell upon a log at the fireplace’s side. It glowed, then flamed, then fell as ash to the ground. “And that is the least of my powers. Can you do as much?”

All night I stared at those logs. I could not.

My sister was born, and my brother soon after that. I cannot say how long it was exactly. Divine days fall like water from a cataract, and I had not learned yet the mortal trick of counting them. You’d think my father would have taught us better, for he, after all, knows every sunrise. But even he used to call my brother and sister twins. Certainly, from the moment of my brother’s birth, they were entwined like minks. My father blessed them both with one hand. “You,” he said to my luminous sister Pasiphae. “You will marry an eternal son of Zeus.” He used his prophecy voice, the one that spoke of future certainties. My mother glowed to hear it, thinking of the robes she would wear to Zeus’ feasts.

“And you,” he said to my brother, in his regular voice, resonant, clear as a summer’s morning. “Every son reflects upon his mother.” My mother was pleased with this, and took it as permission to name him. She called him Perses, for herself.

The two of them were clever and quickly saw how things stood. They loved to sneer at me behind their ermine paws. Her eyes are yellow as piss. Her voice is screechy as an owl. She is called Hawk, but she should be called Goat for her ugliness.

Those were their earliest attempts at barbs, still dull, but day by day they sharpened. I learned to avoid them, and they soon found better sport among the infant naiads and river-lords in Oceanos’ halls. When my mother went to her sisters, they followed and established dominion over all our pliant cousins, hypnotized like minnows before the pike’s mouth. They had a hundred tormenting games that they devised. Come, Melia, they coaxed. It is the Olympian fashion to cut off your hair to the nape of your neck. How will you ever catch a husband if you don’t let us do it? When Melia saw herself shorn like a hedgehog and cried, they would laugh till the caverns echoed.

I left them to it. I preferred my father’s quiet halls and spent every second I could at my father’s feet. One day, perhaps as a reward, he offered to take me with him to visit his sacred herd of cows. This was a great honor, for it meant I might ride in his golden chariot and see the animals that were the envy of all the gods, fifty pure-white heifers that delighted his eye on his daily path over the earth. I leaned over the chariot’s jeweled side, watching in wonder at the earth passing beneath: the rich green of forests, the jagged mountains, and the wide out-flung blue of the ocean. I looked for mortals, but we were too high up to see them.

The herd lived on the grassy island of Thrinakia with two of my half-sisters as caretakers. When we arrived these sisters ran at once to my father and hung from his neck, exclaiming. Of all my father’s beautiful children, they were among the most beautiful, with skin and hair like molten gold. Lampetia and Phaethousa, their names were. Radiant and Shining.

“And who is this you have brought with you?”

“She must be one of Perse’s children, look at her eyes.”

“Of course!” Lampetia, I thought it was Lampetia, stroked my hair. “Darling, your eyes are nothing to worry about. Nothing at all. Your mother is very beautiful, but she has never been strong.”

“My eyes are like yours,” I said.

“How sweet! No, darling, ours are bright as fire, and our hair like sun on the water.”

“You’re clever to keep yours in a braid,” Phaethousa said. “The brown streaking does not look so bad then. It is a shame you cannot hide your voice the same way.”

“She could never speak again. That would work, would it not, sister?”

“So it would.” They smiled. “Shall we go to see the cows?”

I had never seen a cow before, of any kind, but it did not matter: the animals were so obviously beautiful that I needed no comparison. Their coats were pure as lily petals and their eyes gentle and long-lashed. Their horns had been gilded, that was my sisters’ doing, and when they bent to crop the grass, their necks dipped like dancers. In the sunset light, their backs gleamed glossy-soft.

“Oh!” I said. “May I touch one?”

“No,” my father said.

“Shall we tell you their names? That is White-face, and that is Bright-eyes, and that Darling. There is Lovely Girl and Pretty and Golden-horn and Gleaming. There is Darling and there is, ”

“You named Darling already,” I said. “You said that one was Darling.” I pointed to the first cow, peacefully chewing.

My sisters looked at each other, then at my father, a single golden glance. But he was gazing at his cows in abstracted glory.

“You must be mistaken,” they said. “This one we just said is Darling. And this one is Star-bright and this one Flashing and, ”

My father said, “What is this? A scab upon Pretty?”

Immediately my sisters were falling over themselves. “What scab? Oh, it cannot be! Oh, wicked Pretty, to have hurt yourself. Oh, wicked thing, that hurt you!”

I leaned close to see. It was a very small scab, smaller than my smallest fingernail, but my father was frowning. “You will fix it by tomorrow.”

My sisters bobbed their heads, of course, of course. We are so sorry.

We stepped again into the chariot and my father took up the silver-tipped reins. My sisters pressed a last few kisses to his hands, then the horses leapt, swinging us through the sky. The first constellations were already peeping through the dimming light.

I remembered how my father had once told me that on earth there were men called astronomers whose task it was to keep track of his rising and setting. They were held in highest esteem among mortals, kept in palaces as counselors of kings, but sometimes my father lingered over one thing or another and threw their calculations into despair. Then those astronomers were hauled before the kings they served and killed as frauds. My father had smiled when he told me. It was what they deserved, he said. Helios the Sun was bound to no will but his own, and none might say what he would do.

“Father,” I said that day, “are we late enough to kill astronomers?”

“We are,” he answered, shaking the jingling reins. The horses surged forward, and the world blurred beneath us, the shadows of night smoking from the sea’s edge. I did not look. There was a twisting feeling in my chest, like cloth being wrung dry. I was thinking of those astronomers. I imagined them, low as worms, sagging and bent. Please, they cried, on bony knees, it wasn’t our fault, the sun itself was late.

The sun is never late, the kings answered from their thrones. It is blasphemy to say so, you must die! And so the axes fell and chopped those pleading men in two.

“Father,” I said, “I feel strange.”

“You are hungry,” he said. “It is past time for the feast. Your sisters should be ashamed of themselves for delaying us.”

I ate well at dinner, yet the feeling lingered. I must have had an odd look on my face, for Perses and Pasiphae began to snicker from their couch. “Did you swallow a frog?”

“No,” I said.

This only made them laugh harder, rubbing their draped limbs on each other like snakes polishing their scales. My sister said, “And how were our father’s golden heifers?”

“Beautiful.”

Perses laughed. “She doesn’t know! Have you ever heard of anyone so stupid?”

“Never,” my sister said.

I shouldn’t have asked, but I was still drifting in my thoughts, seeing those severed bodies sprawled on marble floors. “What don’t I know?”

My sister’s perfect mink face. “That he fucks them, of course. That’s how he makes new ones. He turns into a bull and sires their calves, then cooks the ones that get old. That’s why everyone thinks they are immortal.”

“He does not.”

They howled, pointing at my reddened cheeks. The sound drew my mother. She loved my siblings’ japes.

“We’re telling Circe about the cows,” my brother told her. “She didn’t know.”

My mother’s laughter, silver as a fountain down its rocks. “Stupid Circe.”

Such were my years then. I would like to say that all the while I waited to break out, but the truth is, I’m afraid I might have floated on, believing those dull miseries were all there was, until the end of days.

Chapter Two.

Word came that one of my uncles was going to be punished. I had never seen him, but I had heard his name over and over in my family’s doomy whispers. Prometheus. Long ago, when mankind was still shivering and shrinking in their caves, he had defied the will of Zeus and brought them the gift of fire. From its flames had sprung all the arts and profits of civilization that jealous Zeus had hoped to keep from their hands. For such rebellion Prometheus had been sent to live in the underworld’s deepest pit until a proper torment could be devised. And now Zeus announced the time was come.

My other uncles ran to my father’s palace, beards flapping, fears spilling from their mouths. They were a motley group: river-men with muscles like the trunks of trees, brine-soaked mer-gods with crabs hanging from their beards, stringy old-timers with seal meat in their teeth. Most of them were not uncles at all, but some sort of grand-cousin. They were Titans like my father and grandfather, like Prometheus, the remnants of the war among the gods. Those who were not broken or in chains, who had made their peace with Zeus’ thunderbolts.

There had only been Titans once, at the dawning of the world. Then my great-uncle Kronos had heard a prophecy that his child would one day overthrow him. When his wife, Rhea, birthed her first babe, he tore it damp from her arms and swallowed it whole. Four more children were born, and he ate them all the same, until at last, in desperation, Rhea swaddled a stone and gave it to him to swallow instead. Kronos was deceived, and the rescued baby, Zeus, was taken to Mount Dicte to be raised in secret. When he was grown he rose up indeed, plucking the thunderbolt from the sky and forcing poisonous herbs down his father’s throat. His brothers and sisters, living in their father’s stomach, were vomited forth. They sprang to their brother’s side, naming themselves Olympians after the great peak where they set their thrones.

The old gods divided themselves. Many threw their strength to Kronos, but my father and grandfather joined Zeus. Some said it was because Helios had always hated Kronos’ vaunting pride, others whispered that his prophetic gift gave him foreknowledge of the outcome of the war. The battles rent the skies: the air itself burned, and gods clawed the flesh from each other’s bones. The land was drenched in boiling gouts of blood so potent that rare flowers sprang up where they fell. At last Zeus’ strength prevailed. He clapped those who had defied him into chains, and the remaining Titans he stripped of their powers, bestowing them on his brothers and sisters and the children he had bred. My uncle Nereus, once the mighty ruler of the sea, was now lackey to its new god, Poseidon. My uncle Proteus lost his palace, and his wives were taken for bed-slaves. Only my father and grandfather suffered no diminishment, no loss of place.

The Titans sneered. Were they supposed to be grateful? Helios and Oceanos had turned the tide of war, everyone knew it. Zeus should have loaded them with new powers, new appointments, but he was afraid, for their strength already matched his own. They looked to my father, waiting for his protest, the flaring of his great fire. But Helios only returned to his halls beneath the earth, far from Zeus’ sky-bright gaze.

Centuries had passed. The earth’s wounds had healed and the peace had held. But the grudges of gods are as deathless as their flesh, and on feast nights my uncles gathered close at my father’s side. I loved the way they lowered their eyes when they spoke to him, the way they went silent and attentive when he shifted in his seat. The wine-bowls emptied and the torches waned. It has been long enough, my uncles whispered. We are strong again. Think what your fire might do if you set it free. You are the greatest of the old blood, greater even than Oceanos. Greater than Zeus himself, if only you wish it.

My father smiled. “Brothers,” he said, “what talk is this? Is there not smoke and savor for all? This Zeus does well enough.”

Zeus, if he had heard, would have been satisfied. But he could not see what I saw, plain on my father’s face. Those unspoken, hanging words.

This Zeus does well enough, for now.

My uncles rubbed their hands and smiled back. They went away, bent over their hopes, thinking what they could not wait to do when Titans ruled again.

It was my first lesson. Beneath the smooth, familiar face of things is another that waits to tear the world in two.

Now my uncles were crowding into my father’s hall, eyes rolling in fear. Prometheus’ sudden punishment was a sign, they said, that Zeus and his kind were moving against us at last. The Olympians would never be truly happy until they destroyed us utterly. We should stand with Prometheus, or no, we should speak against him, to ward off Zeus’ thunderstroke from our own heads.

I was in my customary place at my father’s feet. I lay silent so they would not notice and send me away, but I felt my chest roiling with that overwhelming possibility: the war revived. Our halls blasted wide with thunderbolts. Athena, Zeus’ warrior daughter, hunting us down with her gray spear, her brother in slaughter, Ares, by her side. We would be chained and cast into fiery pits from which there was no escape.

My father spoke calm and golden at their center: “Come, brothers, if Prometheus is to be punished, it is only because he has earned it. Let us not chase after conspiracy.”

But my uncles fretted on. The punishment is to be public. It is an insult, a lesson they teach us. Look what happens to Titans who do not obey.

My father’s light had taken on a keen, white edge. “This is the chastisement of a renegade and no more. Prometheus was led astray by his foolish love for mortals. There is no lesson here for a Titan. Do you understand?”

My uncles nodded. On their faces, disappointment braided with relief. No blood, for now.

The punishment of a god was a rare and terrible thing, and talk ran wild through our halls. Prometheus could not be killed, but there were many hellish torments that could take death’s place. Would it be knives or swords, or limbs torn off? Red-hot spikes or a wheel of fire? The naiads swooned into each other’s laps. The river-lords postured, faces dark with excitement. You cannot know how frightened gods are of pain. There is nothing more foreign to them, and so nothing they ache more deeply to see.

On the appointed day, the doors of my father’s receiving hall were thrown open. Huge torches carbuncled with jewels glowed from the walls and by their light gathered nymphs and gods of every variety. The slender dryads flowed out of their forests, and the stony oreads ran down from their crags. My mother was there with her naiad sisters, the horse-shouldered river-gods crowded in beside the fish-white sea-nymphs and their lords of salt. Even the great Titans came: my father, of course, and Oceanos, but also shape-shifting Proteus and Nereus of the Sea, my aunt Selene, who drives her silver horses across the night sky, and the four Winds led by my icy uncle Boreas. A thousand avid eyes. The only ones missing were Zeus and his Olympians. They disdained our underground gatherings. The word was they had already held their own private session of torment in the clouds.

Charge of the punishment had been given to a Fury, one of the infernal goddesses of vengeance who dwell among the dead. My family was in its usual place of preeminence, and I stood at the front of that great throng, my eyes fixed upon the door. Behind me the naiads and river-gods jostled and whispered. I hear they have serpents for hair. No, they have scorpion tails, and eyes dripping blood.

The doorway was empty. Then at once it was not. Her face was gray and pitiless, as if cut from living rock, and from her back dark wings lifted, jointed like a vulture’s. A forked tongue flicked from her lips. On her head snakes writhed, green and thin as worms, weaving living ribbons through her hair.

“I bring the prisoner.”

Her voice echoed off the ceiling, raw and baying, like a hunting dog calling down its quarry. She strode into the hall. In her right hand was a whip, its tip rasping faintly as it dragged along the floor. In her other hand stretched a length of chain, and at its end followed Prometheus.

He wore a thick white blindfold and the remnants of a tunic around his waist. His hands were bound and his feet too, yet he did not stumble. I heard an aunt beside me whisper that the fetters had been made by the great god of smiths, Hephaestus himself, so not even Zeus could break them. The Fury rose up on her vulture wings and drove the manacles high into the wall. Prometheus dangled from them, his arms drawn taut, his bones showing knobs through the skin. Even I, who knew so little of discomfort, felt the ache of it.

My father would say something, I thought. Or one of the other gods. Surely they would give him some sort of acknowledgment, a word of kindness, they were his family, after all. But Prometheus hung silent and alone.

The Fury did not bother with a lecture. She was a goddess of torment and understood the eloquence of violence. The sound of the whip was a crack like oaken branches breaking. Prometheus’ shoulders jerked and a gash opened in his side long as my arm. All around me indrawn breaths hissed like water on hot rocks. The Fury lifted her lash again. Crack. A bloodied strip tore from his back. She began to carve in earnest, each blow falling on the next, peeling his flesh away in long lines that crossed and recrossed his skin. The only sound was the snap of the whip and Prometheus’ muffled, explosive breaths. The tendons stood out in his neck. Someone pushed at my back, trying for a better view.

The wounds of gods heal fast, but the Fury knew her business and was faster. Blow after blow she struck, until the leather was soaked. I had understood gods could bleed, but I had never seen it. He was one of the greatest of our kind, and the drops that fell from him were golden, smearing his back with a terrible beauty.

Still the Fury whipped on. Hours passed, perhaps days. But even gods cannot watch a whipping for eternity. The blood and agony began to grow tedious. They remembered their comforts, the banquets that were waiting on their pleasure, the soft couches laid with purple, ready to enfold their limbs. One by one they drifted off, and after a final lash, the Fury followed, for she deserved a feast after such work.

The blindfold had slipped from my uncle’s face. His eyes were closed, and his chin drooped on his chest. His back hung in gilded shreds. I had heard my uncles say that Zeus had given him the chance to beg on his knees for lesser punishment. He had refused.

I was the only one left. The smell of ichor drenched the air, thick as honey. The rivulets of molten blood were still tracing down his legs. My pulse struck in my veins. Did he know I was there? I took a careful step towards him. His chest rose and fell with a soft rasping sound.

“Lord Prometheus?” My voice was thin in the echoing room.

His head lifted to me. Open, his eyes were handsome, large and dark and long-lashed. His cheeks were smooth and beardless, yet there was something about him that was as ancient as my grandfather.

“I could bring you nectar,” I said.

His gaze rested on mine. “I would thank you for that,” he said. His voice was resonant as aged wood. It was the first time I had heard it, he had not cried out once in all his torment.

I turned. My breaths came fast as I walked through the corridors to the feasting hall, filled with laughing gods. Across the room, the Fury was toasting with an immense goblet embossed with a gorgon’s leering face. She had not forbidden anyone to speak to Prometheus, but that was nothing, her business was offense. I imagined her infernal voice, howling out my name. I imagined manacles rattling on my wrists and the whip striking from the air. But my mind could imagine no further than that. I had never felt a lash. I did not know the color of my blood.

I trembled so much I had to carry the cup in two hands. What would I say if someone stopped me? But the passageways were quiet as I walked back through them.

In the great hall, Prometheus was silent in his chains. His eyes had closed again, and his wounds shone in the torchlight. I hesitated.

“I do not sleep,” he said. “Will you lift the cup for me?”

I flushed. Of course he could not hold it himself. I stepped forward, so close that I could feel the heat rising from his shoulders. The ground was wet with his fallen blood. I raised the cup to his lips and he drank. I watched his throat moving gently. His skin was beautiful, the color of polished walnut. It smelled of green moss drenched with rain.

“You are a daughter of Helios, are you not?” he said, when he had finished, and I’d stepped back.

“Yes.” The question stung. If I had been a proper daughter, he would not have had to ask. I would have been perfect and gleaming with beauty poured straight from my father’s source.

“Thank you for your kindness.”

I did not know if I was kind, I felt I did not know anything. He spoke carefully, almost tentatively, yet his treason had been so brazen. My mind struggled with the contradiction. Bold action and bold manner are not the same.

“Are you hungry?” I asked. “I could bring you food.”

“I do not think I will ever be hungry again.”

It was not piteous, as it might have been in a mortal. We gods eat as we sleep: because it is one of life’s great pleasures, not because we have to. We may decide one day not to obey our stomachs, if we are strong enough. I did not doubt Prometheus was. After all those hours at my father’s feet, I had learned to nose out power where it lay. Some of my uncles had less scent than the chairs they sat on, but my grandfather Oceanos smelled deep as rich river mud, and my father like a searing blaze of just-fed fire. Prometheus’ green moss scent filled the room.

I looked down at the empty cup, willing my courage.

“You aided mortals,” I said. “That is why you are punished.”

“It is.”

“Will you tell me, what is a mortal like?”

It was a child’s question, but he nodded gravely. “There is no single answer. They are each different. The only thing they share is death. You know the word?”

“I know it,” I said. “But I do not understand.”

“No god can. Their bodies crumble and pass into earth. Their souls turn to cold smoke and fly to the underworld. There they eat nothing and drink nothing and feel no warmth. Everything they reach for slips from their grasp.”

A chill shivered across my skin. “How do they bear it?”

“As best they can.”

The torches were fading, and the shadows lapped at us like dark water. “Is it true that you refused to beg for pardon? And that you were not caught, but confessed to Zeus freely what you did?”

“It is.”

“Why?”

His eyes were steady on mine. “Perhaps you will tell me. Why would a god do such a thing?”

I had no answer. It seemed to me madness to invite divine punishment, but I could not say that to him, not when I stood in his blood.

“Not every god need be the same,” he said.

What I might have said in return, I do not know. A distant shout floated up the corridor.

“It is time for you to go now. Allecto does not like to leave me for long. Her cruelty springs fast as weeds and must any moment be cut again.”

It was a strange way to put it, for he was the one who would be cut. But I liked it, as if his words were a secret. A thing that looked like a stone, but inside was a seed.

“I will go then,” I said. “You will, be well?”

“Well enough,” he said. “What is your name?”

“Circe.”

Did he smile a little? Perhaps I only flattered myself. I was trembling with all I had done, which was more than I had ever done in my life. I turned and left him, walking back through those obsidian corridors. In the feasting hall, gods still drank and laughed and lay across each other’s laps. I watched them. I waited for someone to remark on my absence, but no one did, for no one had noticed. Why would they? I was nothing, a stone. One more nymph child among the thousand thousands.

A strange feeling was rising in me. A sort of humming in my chest, like bees at winter’s thaw. I walked to my father’s treasury, filled with its glittering riches: golden cups shaped like the heads of bulls, necklaces of lapis and amber, silver tripods, and quartz-chiseled bowls with swan-neck handles. My favorite had always been a dagger with an ivory haft carved like a lion’s face. A king had given it to my father in hopes of gaining his favor.

“And did he?” I once asked my father.

“No,” my father had said.

I took the dagger. In my room, the bronze edge shone in the taper’s light and the lion showed her teeth. Beneath lay my palm, soft and unlined. It could bear no scar, no festering wound. It would never wear the faintest print of age. I found that I was not afraid of the pain that would come. It was another terror that gripped me: that the blade would not cut at all. That it would pass through me, like falling into smoke.

It did not pass through. My skin leapt apart at the blade’s touch, and the pain darted silver and hot as lightning strike. The blood that flowed was red, for I did not have my uncle’s power. The wound seeped for a long time before it began to reknit itself. I sat watching it, and as I watched I found a new thought in myself. I am embarrassed to tell it, so rudimentary it seems, like an infant’s discovery that her hand is her own. But that is what I was then, an infant.

The thought was this: that all my life had been murk and depths, but I was not a part of that dark water. I was a creature within it.

Chapter Three.

When I woke, Prometheus was gone. The golden blood had been wiped from the floor. The hole the manacles had made was closed over. I heard the news from a naiad cousin: he had been taken to a great jagged peak in the Caucasus and chained to the rock. An eagle was commanded to come every noon and tear out his liver and eat it steaming from his flesh. Unspeakable punishment, she said, relishing each detail: the bloody beak, the shredded organ re growing only to be ripped forth again. Can you imagine?

I closed my eyes. I should have brought him a spear, I thought, something so he could have fought his way through. But that was foolish. He did not want a weapon. He had given himself up.

Talk of Prometheus’ punishment scarcely lasted out the moon. A dryad stabbed one of the Graces with her hairpin. My uncle Boreas and Olympian Apollo had fallen in love with the same mortal youth.

I waited till my uncles paused in their gossip. “Is there any news of Prometheus?”

They frowned, as if I had offered them a plate of something foul. “What news could there be?”

My palm ached where the blade had cut, though of course there was no mark.

“Father,” I said, “will Zeus ever let Prometheus go?”

My father squinted at his draughts. “He would have to get something better for it,” he said.

“Like what?”

My father did not answer. Someone’s daughter was changed into a bird. Boreas and Apollo quarreled over the youth they loved and he died. Boreas smiled slyly from his feasting couch. His gusty voice made the torches flicker. “You think I’d let Apollo have him? He does not deserve such a flower. I blew a discus into the boy’s head, that showed the Olympian prig.” The sound of my uncles’ laughter was a chaos, the squeaks of dolphins, seal barks, water slapping rocks. A group of nereids passed, eel-belly white, on their way home to their salt halls.

Perses flicked an almond at my face. “What’s wrong with you these days?”

“Maybe she’s in love,” Pasiphae said.

“Hah!” Perses laughed. “Father cannot even give her away. Believe me he’s tried.”

My mother looked back over her delicate shoulder. “At least we don’t have to listen to her voice.”

“I can make her talk, watch.” Perses took the flesh of my arm between his fingers and squeezed.

“You’ve been feasting too much,” my sister laughed at him.

He flushed. “She’s just a freak. She’s hiding something.” He caught me by the wrist. “What’re you always carrying around in your hand? She’s got something. Open her fingers.”

Pasiphae peeled them back one by one, her long nails pricking.

They peered down. My sister spat.

“Nothing.”

My mother whelped again, a boy. My father blessed him, but spoke no prophecy, so my mother looked around for somewhere to leave him. My aunts were wise by then and kept their hands behind their backs.

“I will take him,” I said.

My mother scoffed, but she was eager to show off her new string of amber beads. “Fine. At least you will be of some use. You can squawk at each other.”

Aeetes, my father had named him. Eagle. His skin was warm in my arms as a sun-hot stone and soft as petal-velvet. There had never been a sweeter child. He smelled like honey and just-kindled flames. He ate from my fingers and did not flinch at my frail voice. He only wanted to sleep curled against my neck while I told him stories. Every moment he was with me, I felt a rushing in my throat, which was my love for him, so great sometimes I could not speak.

He seemed to love me back, that was the greater wonder. Circe was the first word he ever spoke, and the second was sister. My mother might have been jealous, if she had noticed. Perses and Pasiphae eyed us, to see if we would start a war. A war? We did not care for that. Aeetes got permission from Father to leave the halls and found us a deserted seaside. The beach was small and pale and the trees barely scrub, but to me it seemed a great, lush wilderness.

In a wink he was grown and taller than I was, but still we would walk arm in arm. Pasiphae jeered that we looked like lovers, would we be those types of gods, who coupled with their siblings? I said if she thought of it, she must have done it first. It was a clumsy insult, but Aeetes laughed, which made me feel quick as Athena, flashing god of wit.

Later, people would say that Aeetes was strange because of me. I cannot prove it was not so. But in my memory he was strange already, different from any other god I knew. Even as a child, he seemed to understand what others did not. He could name the monsters who lived in the sea’s darkest trenches. He knew that the herbs Zeus had poured down Kronos’ throat were called pharmaka. They could work wonders upon the world, and many grew from the fallen blood of gods.

I would shake my head. “How do you hear such things?”

“I listen.”

I had listened too, but I was not my father’s favored heir. Aeetes was summoned to sit in on all his councils. My uncles had begun inviting him to their halls. I waited in my room for him to come back, so we could go together to that deserted shore and sit on the rocks, the sea spray at our feet. I would lean my cheek upon his shoulder and he would ask me questions that I had never thought of and could barely understand, like: How does your divinity feel?

“What do you mean?” I said.

“Here,” he said, “let me tell you how mine feels. Like a column of water that pours ceaselessly over itself, and is clear down to its rocks. Now, you.”

I tried answers: like breezes on a crag. Like a gull, screaming from its nest.

He shook his head. “No. You are only saying those things because of what I said. What does it really feel like? Close your eyes and think.”

I closed my eyes. If I had been a mortal, I would have heard the beating of my heart. But gods have sluggish veins, and the truth is, what I heard was nothing. Yet I hated to disappoint him. I pressed my hand to my chest, and after a little it did seem that I felt something. “A shell,” I said.

“Aha!” He shook his finger in the air. “A shell like a clam or like a conch?”

“A conch.”

“And what is in that shell? A snail?”

“Nothing,” I said. “Air.”

“Those are not the same,” he said. “Nothing is empty void, while air is what fills all else. It is breath and life and spirit, the words we speak.”

My brother, the philosopher. Do you know how many gods are such? Only one other that I had met. The blue sky arched above us, but I was in that old dark hall again, with its manacles and blood.

“I have a secret,” I said.

Aeetes lifted his brows, amused. He thought it was a joke. I had never known anything he did not.

“It was before you were born,” I said.

Aeetes did not look at me while I told him about Prometheus. His mind worked best, he always said, without distractions. His eyes were fixed on the horizon. They were sharp as the eagle he was named for, and could pry into all the cracks of things, like water pricking at a leaky hull.

When I was finished, he was silent a long time. At last he said: “Prometheus was a god of prophecy. He would have known he would be punished, and how. Yet he did it anyway.”

I had not thought of that. How even as Prometheus took up the flame for mankind, he would have known he was walking towards the eagle and that desolate, eternal crag.

Well enough, he had answered, when I had asked how he would be.

“Who else knows this?”

“No one.”

“You are sure?” His voice had an urgency to it I was not used to. “You did not tell anyone?”

“No,” I said. “Who else is there? Who would have believed me?”

“True.” He nodded once. “You must tell no one else. You should not talk about it again, even with me. You are lucky Father did not find out.”

“You think he would be so angry? Prometheus is his cousin.”

He snorted. “We are all cousins, including the Olympians. You would make Father look like a fool who cannot control his offspring. He would throw you to the crows.”

I felt my stomach clench with dread, and my brother laughed at the look on my face. “Exactly,” he said. “And for what? Prometheus is punished anyway. Let me give you some advice. Next time you’re going to defy the gods, do it for a better reason. I’d hate to see my sister turned to cinders for nothing.”

Pasiphae was contracted in marriage. She had been angling for it a long time, sitting in my father’s lap and purring of how she longed to bear a good lord children. My brother Perses had been enlisted to help her, lifting goblets to toast her nubility at every meal.

“Minos,” my father said from his feasting couch. “A son of Zeus and king of Crete.”

“A mortal?” My mother sat up. “You said it would be a god.”

“I said he would be an eternal son of Zeus, and so he is.”

Perses sneered. “Prophecy talk. Does he die or not?”

A flash in the room, searing as the fire’s heart. “Enough! Minos will rule all the other mortal souls in the afterlife. His name will go on through the centuries. It is done.”

My brother dared say no more, nor my mother. Aeetes caught my eye, and I heard his words as if he spoke them. See? Not a good enough reason.

I expected my sister to weep over her demotion. But when I looked, she was smiling. What that meant I could not say, my mind was following a different thread. A flush had spread over my skin. If Minos were there, so would his family be, his court, his advisers, his vassals and astronomers, his cupbearers, his servants and underservants. All those creatures Prometheus had given his eternity for. Mortals.

On the wedding day, my father carried us across the sea in his golden chariot. The feast was to be held on Crete, in Minos’ great palace at Knossos. The walls were new-plastered and every surface hung with bright flowers, the tapestries glowed with richest saffron. Not only Titans would attend. Minos was a son of Zeus, and all the boot-licking Olympians would also come to pay their homage. The long colonnades filled up quickly with gods in their glory, clattering their adornments, laughing, casting glances to see who else had been invited. The thickest knot was around my father, immortals of every sort pressing in to congratulate him on his brilliant alliance. My uncles were especially pleased: Zeus was unlikely to move against us as long as the marriage held.

From her bridal dais Pasiphae glowed lush as ripe fruit. Her skin was gold, and her hair the color of sun on polished bronze. Around her crowded a hundred eager nymphs, each more desperate than the last to tell her how beautiful she looked.

I stood back, out of the crush. Titans passed before me: my aunt Selene, my uncle Nereus trailing seaweed, Mnemosyne, mother of memories, and her nine light-footed daughters. My eyes skimmed over, searching.

I found them at last at the hall’s edge. A dim huddle of figures, heads bent together. Prometheus had told me they were each different, but all I could make out was an indistinguished crowd, each with the same dull and sweated skin, the same wrinkled robes. I moved closer. Their hair hung lank, their flesh drooped soft off their bones. I tried to imagine going up to them, touching my hand to that dying skin. The thought sent a shiver through me. I had heard by then the stories whispered among my cousins, of what they might do to nymphs they caught alone. The rapes and ravishments, the abuses. I found it hard to believe. They looked weak as mushroom gills. They kept their faces carefully down, away from all those divinities. Mortals had their own stories, after all, of what happened to those who mixed with gods. An ill-timed glance, a foot set in an impropitious spot, such things could bring down death and woe upon their families for a dozen generations.

It was like a great chain of fear, I thought. Zeus at the top and my father just behind. Then Zeus’ siblings and children, then my uncles, and on down through all the ranks of river-gods and brine-lords and Furies and Winds and Graces, until it came to the bottom where we sat, nymphs and mortals both, each eyeing the other.

Aeetes’ hand closed on my arm. “Not much to look at, are they? Come on, I found the Olympians.”

I followed, my blood beating within me. I had never seen one before, those deities who rule from their celestial thrones. Aeetes drew me to a window overlooking a sun-dazzled courtyard. And there they were: Apollo, lord of the lyre and the gleaming bow. His twin, moonlit Artemis, the pitiless huntress. Hephaestus, blacksmith of the gods, who had made the chains that held Prometheus still. Brooding Poseidon, whose trident commands the waves, and Demeter, lady of bounty, whose harvests nourish all the world. I stared at them, gliding sleek in their power. The very air seemed to give way where they walked.

“Do you see Athena?” I whispered. I had always liked the stories of her, gray-eyed warrior, goddess of wisdom, whose mind was swifter than the lightning bolt. But she was not there. Perhaps, Aeetes said, she was too proud to rub shoulders with earthbound Titans. Perhaps she was too wise to offer compliments as one among a crowd. Or perhaps she was there after all, but concealed even from the eyes of other divinities. She was one of the most powerful of the Olympians, she could do such a thing, and so observe the currents of power, and listen to our secrets.

My neck turned to gooseflesh at the thought. “Do you think she listens to us even now?”

“Don’t be foolish. She is here for the great gods. Look, Minos comes.”

Minos, king of Crete, son of Zeus and a mortal woman. A demigod, his kind were called, mortal themselves but blessed by their divine parentage. He towered over his advisers, his hair thick as matted brush and his chest broad as the deck of a ship. His eyes reminded me of my father’s obsidian halls, shining darkly beneath his golden crown. Yet when he placed his hand on my sister’s delicate arm, suddenly he looked like a tree in winter, bare and shriveled-small. He knew it, I think, and glowered, which made my sister glitter all the more. She would be happy here, I thought. Or preeminent, which was the same to her.

“There,” Aeetes said, leaning close to my ear. “Look.”

He was pointing to a mortal, a man I had not noticed before, not quite so huddled as the rest. He was young, his head shaved clean in the Egyptian style, the skin of his face fitted comfortably into its lines. I liked him. His clear eyes were not smoked with wine like everybody else’s.

“Of course you like him,” Aeetes said. “It is Daedalus. He is one of the wonders of the mortal world, a craftsman almost equal to a god. When I am my own king, I will collect such glories around me too.”

“Oh? And when will you be king?”

“Soon,” he said. “Father is giving me a kingdom.”

I thought he was joking. “And may I live there?”

“No,” he said. “It is mine. You will have to get your own.”

His arm was through mine as it ever was, yet suddenly all was different, his voice swinging free, as if we were two creatures tied to separate cords, instead of to each other.

“When?” I croaked.

“After this. Father plans to take me straight.”

He said it as if it were no more than a point of minor interest. I felt like I was turning to stone. I clung to him. “How could you not tell me?” I began. “You cannot leave me. What will I do? You do not know what it was like before, ”

He drew my arms back from his neck. “There is no need for such a scene. You knew this would come. I cannot rot all my life underground, with nothing of my own.”

What of me? I wanted to ask. Shall I rot?

But he had turned away to speak to one of my uncles, and as soon as the wedded pair was in their bedchamber, he stepped onto my father’s chariot. In a whirl of gold, he was gone.

Perses left a few days later. No one was surprised, those halls of my father were empty for him without my sister. He said he was going east, to live among the Persians. Their name is like mine, he said, fatuously. And I hear they raise creatures called demons, I would like to see one.

My father frowned. He had taken against Perses ever since he had mocked him over Minos. “Why should they have demons, more than us?”

Perses did not bother to answer. He would go through the ways of water, he did not need my father to ferry him. At least I will not have to hear that voice of yours anymore, was the last thing he said to me.

In a handful of days, all my life had been unwound. I was a child again, waiting while my father drove his chariot, while my mother lounged by Oceanos’ riverbanks. I lay in our empty halls, my throat scraping with loneliness, and when I could not bear it any longer, I fled to Aeetes and my old deserted shore. There I found the stones Aeetes’ fingers had touched. I walked the sand his feet had turned. Of course he could not stay. He was a divine son of Helios, bright and shining, true-voiced and clever, with hopes of a throne. And I?

I remembered his eyes as I had pleaded with him. I knew him well, and could read what was in them when he looked at me. Not a good enough reason.

I sat on the rocks and thought of the stories I knew of nymphs who wept until they turned into stones and crying birds, into dumb beasts and slender trees, thoughts barked up for eternity. I could not even do that, it seemed. My life closed me in like granite walls. I should have spoken to those mortals, I thought. I could have begged among them for a husband. I was a daughter of Helios, surely one of those ragged men would have had me. Anything would be better than this.

And that is when I saw the boat.

Chapter Four.

I knew of ships from paintings, I had heard of them in stories. They were golden and huge as leviathans, their rails carved from ivory and horn. They were towed by grinning dolphins or else crewed by fifty black-haired nereids, faces silver as moonlight.

This one had a mast thin as a sapling. Its sail hung skewed and fraying, its sides were patched. I remember the jump in my throat when the sailor lifted his face. Burnt it was, and shiny with sun. A mortal.

Mankind was spreading across the world. Years had passed since my brother had first found that deserted land for our games. I stood behind a jut of cliff and watched as the man steered, skirting rocks and hauling at the nets. He looked nothing like the well-groomed nobles of Minos’ court. His hair was long and black, draggled from wave-spray. His clothes were worn, and his neck scabbed. Scars showed on his arms where fish scales had cut him. He did not move with unearthly grace, but strongly, cleanly, like a well-built hull in the waves.

I could hear my pulse, loud in my ears. I thought again of those stories of nymphs ravished and abused by mortals. But this man’s face was soft with youth, and the hands that drew up his catch looked only swift, not cruel. Anyway, in the sky above me was my father, called the Watchman. If I was in danger, he would come.

He was close to the shore by then, peering down into the water, tracking some fish I could not see. I took a breath and stepped forward onto the beach.

“Hail, mortal.”

He fumbled his nets but did not drop them. “Hail,” he said. “What goddess do I address?”

His voice was gentle in my ears, sweet as summer winds.

“Circe,” I said.

“Ah.” His face was carefully blank. He told me much later it was because he had not heard of me and feared to give offense. He knelt on the rough boards. “Most reverend lady. Do I trespass on your waters?”

“No,” I said. “I have no waters. Is that a boat?”

Expressions passed across his face, but I could not read them. “It is,” he said.

“I would like to sail upon it,” I said.

He hesitated, then began to steer closer to the shore, but I did not know to wait. I waded out through the waves to him and pulled myself aboard. The deck was hot through my sandals, and its motion pleasing, a faint undulation, like I rode upon a snake.

“Proceed,” I said.

How stiff I was, dressed in my divine dignity that I did not even know I wore. And he was stiffer still. He trembled when my sleeve brushed his. His eyes darted whenever I addressed him. I realized with a shock that I knew such gestures. I had performed them a thousand times, for my father, and my grandfather, and all those mighty gods who strode through my days. The great chain of fear.

“Oh, no,” I said to him. “I am not like that. I have scarcely any powers at all and cannot hurt you. Be comfortable, as you were.”

“Thank you, kind goddess.” But he said it so flinchingly that I had to laugh. It was that laughter, more than my protestation, that seemed to ease him a little. Moment passed into moment, and we began to talk of the things around us: the fish jumping, a bird dipping overhead. I asked him how his nets were made, and he told me, warming to the subject, for he took great care with them. When I told him my father’s name, it sent him glancing at the sun and trembling worse than ever, but at day’s end no wrath had descended and he knelt to me and said that I must have blessed his nets, for they were the fullest they had ever been.

I looked down at his thick, black hair, shining in the sunset light, his strong shoulders bowing low. This is what all those gods in our halls longed for, such worship. I thought perhaps he had not done it right, or more likely, I had not. All I wanted was to see his face again.

“Rise,” I told him. “Please. I have not blessed your nets, I have no powers to do so. I am born from naiads, who govern fresh water only, and even their small gifts I lack.”

“Yet,” he said, “may I return? Will you be here? For I have never known such a wondrous thing in all my life as you.”

I had stood beside my father’s light. I had held Aeetes in my arms, and my bed was heaped with thick-wooled blankets woven by immortal hands. But it was not until that moment that I think I had ever been warm.

“Yes,” I told him. “I will be here.”

His name was Glaucos, and he came every day. He brought along bread, which I had never tasted, and cheese, which I had, and olives that I liked to see his teeth bite through. I asked him about his family, and he told me that his father was old and bitter, always storming and worrying about food, and his mother used to make herb simples but was broken now from too much labor, and his sister had five children already and was always sick and angry. All of them would be turned out of their cottage if they could not give their lord the tribute he levied.

No one had ever confided so in me. I drank down every story like a whirlpool sucks down waves, though I could hardly understand half of what they meant, poverty and toil and human terror. The only thing that was clear was Glaucos’ face, his handsome brow and earnest eyes, wet a little from his griefs but smiling always when he looked at me.

I loved to watch him at his daily tasks, which he did with his hands instead of a blink of power: mending the torn nets, cleaning off the boat’s deck, sparking the flint. When he made his fire, he would start painstakingly with small bits of dried moss placed just so, then the smaller twigs, then larger, building upwards and upwards. This art too, I did not know. Wood needed no coaxing for my father to kindle it.

He saw me watching and rubbed self-consciously at his calloused hands. “I know I am ugly to you.”

No, I thought. My grandfather’s halls are filled with shining nymphs and muscled river-gods, but I would rather gaze on you than any of them.

I shook my head.

He sighed. “It must be wonderful to be a god and never bear a mark.”

“My brother once said it feels like water.”

He considered. “Yes, I can imagine that. As if you are brimming, like an overfilled cup. What brother is that? You have not spoken of him before.”

“He is gone to be a king far away. Aeetes, he is called.” The name felt strange on my tongue after so long. “I would have gone with him, but he said no.”

“He sounds like a fool,” Glaucos said.

“What do you mean?”

He lifted his eyes to mine. “You are a golden goddess, beautiful and kind. If I had such a sister, I would never let her go.”

Our arms would brush as he worked at the ship’s rail. When we sat, my dress lapped over his feet. His skin was warm and slightly roughened. Sometimes I would drop something, so he might pick it up, and our hands would meet.

That day, he knelt on the beach, kindling a fire to cook his lunch. It was still one of my favorite things to watch, that simple, mortal miracle of flint and tinder. His hair hung sweetly into his eyes, and his cheeks glowed with the flame’s light. I found myself thinking of my uncle who had given him that gift.

“I met him once,” I said.

Glaucos had spitted a fish and was roasting it. “Who?”

“Prometheus,” I said. “When Zeus punished him, I brought him nectar.”

He looked up. “Prometheus,” he said.

“Yes.” He was not usually so slow. “Fire-bearer.”

“That is a story from a dozen generations ago.”

“More than a dozen,” I said. “Watch out, your fish.” The spit had drooped from his hand, and the fish was blackening on the coals.

He did not rescue it. His eyes were fixed on me. “But you are my age.”

My face had tricked him. It looked as young as his.

I laughed. “No. I am not.”

He had been half slouched to one side, knees touching mine. Now he jerked upright, pulling away from me so fast I felt the cold where he had been. It surprised me.

“Those years are nothing,” I said. “I made no use of them. You know as much of the world as I do.” I reached for his hand.

He yanked it away. “How can you say that? How old are you? A hundred? Two hundred?”

I almost laughed again. But his neck was rigid, and his eyes wide. The fish smoked between us in the fire. I had told him so little of my life. What was there to tell? Only the same cruelties, the same sneers at my back. In those days, my mother was in an especial ill humor. My father had begun to prefer his draughts to her, and her venom over it fell to me. She would curl her lip when she saw me. Circe is dull as a rock. Circe has less wit than bare ground. Circe’s hair is matted like a dog’s. If I have to hear that broken voice of hers once more. Of all our children, why must it be she who is left? No one else will have her. If my father heard, he gave no sign, only moved his game counters here and there. In the old days, I would have crept to my room with tear-stained cheeks, but since Glaucos’ coming it was all like bees without a sting.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “It was only a stupid joke. I never met him, I only wished to. Never fear, we are the same age.”

Slowly, his posture loosened. He blew out a breath. “Hah,” he said. “Can you imagine? If you had really been alive then?”

He finished his meal. He threw the scraps to the gulls, then chased them wheeling to the sky. He turned back to grin at me, outlined against the silver waves, his shoulders lifting in his tunic. No matter how many fires I watched him make, I never spoke of my uncle again.

One day, Glaucos’ boat came late. He did not anchor it, only stood upon its deck, his face stiff and grim. There was a bruise on his cheek, storm-wave dark. His father had struck him.

“Oh!” My pulse leapt. “You must rest. Sit with me, and I will bring you water.”

“No,” he said, and his voice was sharp as I had ever heard it. “Not today, not ever again. Father says I loaf and all our hauls are down. We will starve, and it is my fault.”

“Yet come sit, and let me help,” I said.

“You cannot do anything,” he said. “You told me so. You have no powers at all.”

I watched him sail off. Then wild I turned and ran to my grandfather’s palace. Through its arched passageways I went, to the women’s halls, with their clatter of shuttles and goblets and the jangle of bracelets on wrists. Past the naiads, past the visiting nereids and dryads, to the oaken stool on the dais, where my grandmother ruled.

Tethys, she was called, great nurse of the world’s waters, born like her husband at the dawn of ages from Mother Earth herself. Her robes puddled blue at her feet, and around her neck was wrapped a water-serpent like a scarf. Before her was a golden loom that held her weaving. Her face was old but not withered. Countless daughters and sons had been birthed from her flowing womb, and their descendants were still brought to her for blessing. I myself had knelt to her once. She had touched my forehead with the tips of her soft fingers. Welcome, child.

I knelt again, now. “I am Circe, Perse’s daughter. You must help me. There is a mortal who needs fish from the sea. I cannot bless him, but you can.”

“He is noble?” she asked.

“In nature,” I said. “Poor in possessions, yet rich in spirit and courage, and shining like a star.”

“And what does this mortal offer you in exchange?”

“Offer me?”

She shook her head. “My dear, they must always offer something, even if it is small, even if only wine poured at your spring, else they will forget to be grateful, after.”

“I do no

-

11:25

11:25

PukeOnABook

1 month agoRahan. Episode 119. By Roger Lecureux. The great fear of Rahan. A Puke (TM) Comic.

54 -

59:38

59:38

The Tom Renz Show

16 hours ago"MAGA & Unity With Pastor Bernadette Smith"

8.34K1 -

2:12

2:12

Memology 101

12 hours ago $2.35 earnedTYT's Cenk Uygur DESTROYS deluded self-proclaimed election Nostradamus over FAILED prediction "keys"

8.09K11 -

2:11

2:11

BIG NEM

13 hours agoMeet the NATIVE Tribe Of The Balkans Nobody Talks About

4.94K2 -

2:40:31

2:40:31

Fresh and Fit

11 hours agoAre You Smarter Than A 5th Grader? After Hours

185K77 -

4:07:42

4:07:42

Alex Zedra

17 hours agoLIVE! Scary Games with the Girls

164K6 -

22:35

22:35

DeVory Darkins

14 hours ago $27.93 earned"Don't Call Me Stupid!" Election Guru HUMILIATED by Left Wing Host

73.6K76 -

1:41:14

1:41:14

Megyn Kelly

15 hours agoMace's Quest to Protect Women's Spaces, and RFK vs. Media and Swamp, w/ Casey Means and Vinay Prasad

83.4K118 -

5:08:25

5:08:25

Drew Hernandez

13 hours agoLAKEN RILEY'S KILLER CONVICTED & GIVEN LIFE IN PRISON

65.6K88 -

59:31

59:31

Man in America

17 hours agoEven WW3 Can't Stop What's Coming—the Cabal is COLLAPSING w/ Todd Callender

126K84