Premium Only Content

The Deadly 1993 Waco Siege (2024)

Chronology of the events of April 19

Time Event

05:50 Agents call the Branch Davidian compound to warn they are going to begin tank activity and advise residents "to take cover". Agents say the Branch Davidian who answered the phone did not reply but instead threw the phone and phone line out of the front door.

05:55 The FBI Hostage Rescue Team deploys two armored CEVs to the buildings. CEV1 goes to the left of the buildings, CEV2 to the right.[95]

06:00 FBI surveillance tapes from devices planted in the wall of the building record a man inside the compound saying "Everybody wake up, let's start to pray", then, "Pablo, have you poured it yet?" ..."Huh?" ..."Have you poured it yet?" ..."In the hallway" ..."Things are poured, right?" CEV1 receives orders to spray two bottles of tear gas into left corner of building.[95]

06:05 Armored vehicle with ram and delivery device to pump tear gas into building with pressurized air rips into front wall just left of front door, leaving a hole 8 feet (2.4 m) high and 10 feet (3.0 m) wide. Agents claimed the holes allowed insertion of the gas as well as provided a means of escape. Agent sees shots from inside the compound directed at CEVs.[95]

06:10 FBI surveillance tapes record "Don't pour it all out, we might need some later" and "Throw the tear gas back out." FBI negotiator Byron Sage is recorded saying "It's time for people to come out." Surveillance tapes record a man saying "What?", and then "No way."

06:12 FBI surveillance tapes record Branch Davidians saying "They're gonna kill us", then "They don't want to kill us."

06:31 The entire building is gassed.[95]

06:47 The FBI Hostage Rescue Team fires plastic, non-incendiary tear gas rounds through windows.[95]

07:23 FBI surveillance tapes record a male Branch Davidian saying, "The fuel has to go all around to get started." Then a second male says, "Well, there are two cans here, if that's poured soon."

07:30 CEV1 is redeployed, breaching the building and inserting tear gas. Branch Davidians fire shots at CEV1.[95]

07:45-07:48:52 On FBI tapes of agents recorded during the siege, an FBI Hostage Rescue Team agent requests permission to fire military tear gas rounds to break through an underground concrete bunker. This permission is granted.[94]: 118–119

07:58 CEV2, with battering ram, rips a hole into second floor of compound; minutes later another hole is punched into the rear of one of the buildings of the compound. The vehicles then withdraw.[95]

08:08 Three pyrotechnic military tear gas rounds are shot at the concrete construction pit (not the concrete bunker), away and downwind from the main quarters, trying to penetrate the structure, but they bounce off.[94]: 28–32, 118 An agent in the CEV reports that one shell bounced off bunker and did not penetrate.[95][94]: 30 These are the only military tear gas rounds to be fired by the FBI.[94]: 119

08:24 The audio portion of FBI videotape ends, at the request of the pilot.[95]

09:00 The Branch Davidians unfurl a banner that reads "We want our phone fixed."

09:13 CEV1 breaks through the front door to deliver more gas.[95]

09:20 FBI surveillance records a meeting starting at 7:30 am between several unidentified males.[96]

UM: "They got two cans of Coleman fuel down there? Huh?"

UM: "Empty."

UM: "All of it?"

UM: "Nothing left."

10:00 A man is seen waving a white flag on the southeast side of the compound. He is advised over loudspeakers that if he is surrendering he should come out. He does not. At the same time, a man believed to be Steve Schneider comes out from the remains of the front door to retrieve the phone and phone line.

11:30 The original CEV2 has mechanical difficulties (damaged tread); its replacement breaches through back side of compound.[95]

11:17–12:04 According to the government, a series of remarks such as "I want a fire", "Keep that fire going", and "Do you think I could light this soon?" indicate that the Branch Davidians have started setting fire to the complex around 11:30.[94]: 15–19 [96]: 287 Surviving Branch Davidians testified that Coleman fuel had been poured, and fire experts in Danforth's report agree "without question" that people inside the complex had started multiple accelerated fires.[94]: 15–19, appendixes D and E

11:43 Another gas insertion takes place, with the armored vehicle moving well into the building on the right rear side to reach the concrete interior room where the FBI Hostage Rescue Team believe the Branch Davidians are trying to avoid the gas.

11:45 The wall on the right rear side of the building collapses.[95]

12:03 An armored vehicle turret knocks away the first floor corner on the right side.

12:07 The first visible flames appear in two spots in the front of the building, first on the left of the front door on the second floor (a wisp of smoke then a small flicker of flame), then a short time later on the far right side of the front of the building, and at a third spot on the backside. An FBI Hostage Rescue Team agent reported seeing a Branch Davidian member igniting a fire in the front door area.[94]: 18

12:09 Ruth Riddle exits with a floppy disk in her jacket containing Koresh's Manuscript on the Seven Seals. A third fire is detected on first floor.[95]

12:10 Flames spread quickly through the building, fanned by high winds and the openings created by the FBI. The building burns very quickly.

12:12 No fire trucks were on site so an emergency call is placed regarding the fire. Two Waco Fire Department trucks are dispatched. Shortly after, the Bellmead Fire Department dispatches two trucks.

12:22 Waco fire trucks arrive at the checkpoint, where they are halted (not being allowed to pass until 12:37);[97] Bellmead follows shortly after.

12:25 There is a large explosion on the left side of the compound. One object hurtles into the air, bounces off the top of a bus, and lands on the grass.

12:30 Part of the roof collapses. Around this time, there are several further explosions, and witnesses report the sound of gunfire, attributed by the FBI Hostage Rescue Team to live ammunition cooking off throughout the buildings because of the fire.

12:43 According to fire department logs, fire trucks arrive at the compound.

12:55 Fire begins to burn out. The entire compound is leveled.

15:45 A law enforcement source states that David Koresh is dead.

Aftermath

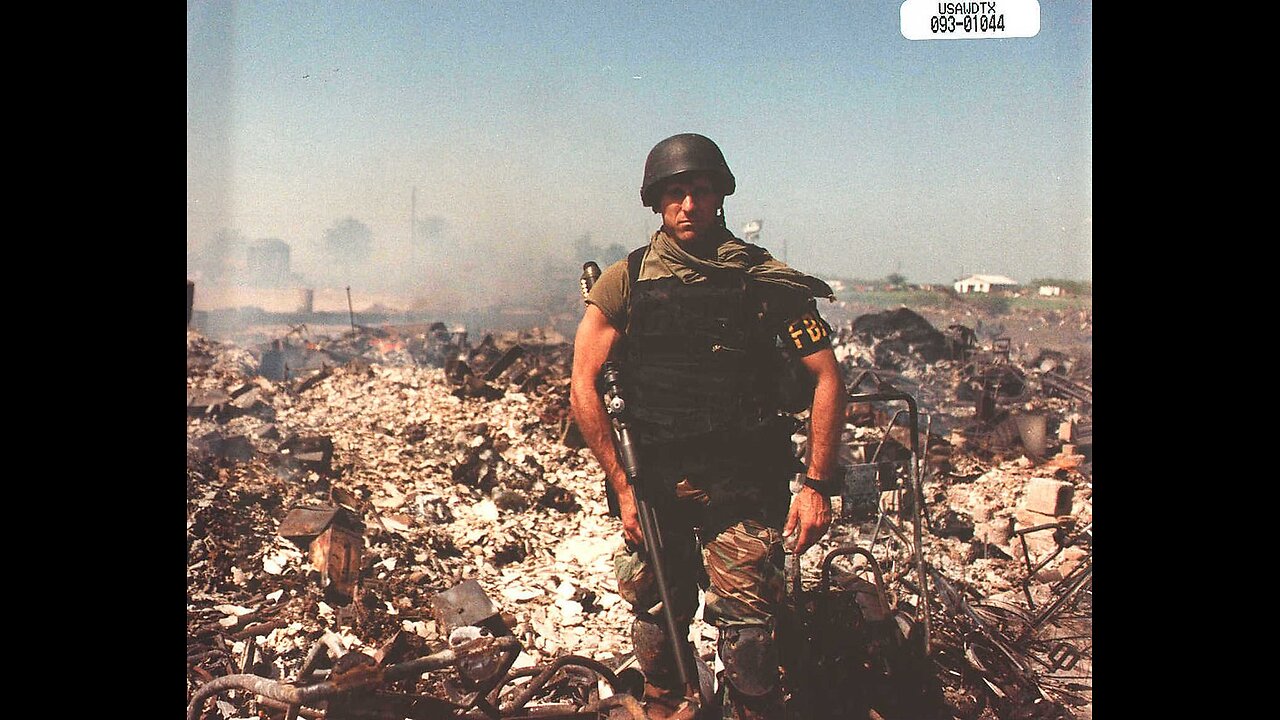

An FBI HRT sniper poses for a photograph in the remains of the burned building.

The remains of a swimming pool on the site of the compound in 1997

The new ATF Director, John Magaw, criticized several aspects of the ATF raid. Magaw made the Treasury "Blue Book" report on Waco required reading for new agents. A 1995 Government Accountability Office report on the use of force by federal law enforcement agencies observed that "On the basis of Treasury's report on the Waco operation and views of tactical operations experts and ATF's own personnel, ATF decided in October 1995 that dynamic entry would only be planned after all other options have been considered and began to adjust its training accordingly."[98]

Nothing remains of the buildings today other than concrete foundation components, as the entire site was bulldozed two weeks after the end of the siege. Only a small chapel, built years after the siege, stands on the site.[99]

FBI's post-Waco adjustments

The Waco siege prompted the FBI to reevaluate its tactics and procedures. The agency made several adjustments in response to the criticism it faced. Firstly, there was a greater emphasis on crisis negotiation and peaceful resolutions, leading to increased training and the establishment of specialized negotiation teams. Secondly, the Hostage Rescue Team underwent enhancements in terms of training, equipment, and coordination to improve their effectiveness in high-risk operations. Additionally, interagency cooperation was emphasized to facilitate better coordination and information sharing among federal entities involved in complex operations. The FBI also recognized the value of intelligence gathering and analysis, leading to a focus on enhancing intelligence capabilities. Lastly, after-action reviews were conducted, and lessons learned were incorporated into training programs to better prepare agents for future situations.

Trial and imprisonments of Branch Davidians

The events at Mount Carmel spurred both criminal prosecution and civil litigation. On August 3, 1993, a federal grand jury returned a superseding ten-count indictment against 12 of the surviving Branch Davidians. The grand jury charged, among other things, that the Branch Davidians had conspired to, and aided and abetted in, the murder of federal officers, and had unlawfully possessed and used various firearms. The government dismissed the charges against one of the 12 Branch Davidians according to a plea bargain.

After a jury trial lasting nearly two months, the jury acquitted four of the Branch Davidians on all charges. Additionally, the jury acquitted all of the Branch Davidians on the murder-related charges but convicted five of them on lesser charges, including aiding and abetting the voluntary manslaughter of federal agents.[100] Eight Branch Davidians were convicted on firearms charges.

The convicted Branch Davidians, who received sentences of up to 40 years,[101] were:

Kevin A. Whitecliff – convicted of voluntary manslaughter and using a firearm during a crime.

Jaime Castillo – convicted of voluntary manslaughter and using a firearm during a crime.

Paul Gordon Fatta – convicted of conspiracy to possess machine guns and aiding Branch Davidian leader David Koresh in possessing machine guns.

Renos Lenny Avraam (British national) – convicted of voluntary manslaughter and using a firearm during a crime.

Graeme Leonard Craddock (Australian national) – convicted of possessing a grenade and using or possessing a firearm during a crime.

Brad Eugene Branch – convicted of voluntary manslaughter and using a firearm during a crime.

Livingstone Fagan (British national) – convicted of voluntary manslaughter and using a firearm during a crime.

Ruth Riddle (Canadian national) – convicted of using or carrying a weapon during a crime.

Kathy Schroeder – sentenced to three years after pleading guilty to a reduced charge of forcibly resisting arrest.

Six of the eight Branch Davidians appealed both their sentences and their convictions. They raised a host of issues, challenging the constitutionality of the prohibition on possession of machine guns, the jury instructions, the district court's conduct of the trial, the sufficiency of the evidence, and the sentences imposed. The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit vacated the defendants' sentences for use of machine guns, determining that the district court had made no finding that they had "actively employed" the weapons, but left the verdicts undisturbed in all other respects, in United States v. Branch,[102] 91 F.3d 699 (5th Cir. 1996), cert. denied (1997).

On remand, the district court found that the defendants had actively employed machine guns and re-sentenced five of them to substantial prison terms. The defendants again appealed. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed.[103] The Branch Davidians pressed this issue before the United States Supreme Court. The Supreme Court reversed, holding that the term "machine gun" in the relevant statute created an element of the offense to be determined by a jury, rather than a sentencing factor to be determined by a judge, as had happened in the trial court.[104] On September 19, 2000, Judge Walter Smith followed the Supreme Court's instructions and cut 25 years from the sentences of five convicted Branch Davidians, and five years from the sentence of another.[105] All Branch Davidians have been released from prison as of July 2007.[106]

Thirty-three British citizens were among the members of the Branch Davidians during the siege. Twenty-four of them were among the 80 Branch Davidian fatalities (in the raid of February 28 and the assault of April 19), including at least one child.[70] Two more British nationals who survived the siege were immediately arrested as "material witnesses" and imprisoned without trial for months.[101] Derek Lovelock was held in McLennan County Jail for seven months, often in solitary confinement.[101] Livingstone Fagan, another British citizen, who was among those convicted and imprisoned, says he received multiple beatings at the hands of correctional officers, particularly at Leavenworth. There, Fagan claims to have been doused inside his cell with cold water from a high-pressure hose, after which an industrial fan was placed outside the cell, blasting him with cold air. Fagan was repeatedly moved between at least nine different facilities. He was strip-searched every time he took exercise, so he refused exercise. Released and deported back to the UK in July 2007, he still retained his religious beliefs.[101]

Civil suits by Branch Davidians

Several of the surviving Branch Davidians, as well as more than a hundred family members of those who had died or were injured in the confrontation, brought civil suits against the United States government, numerous federal officials, the former governor of Texas Ann Richards, and members of the Texas Army National Guard. They sought monetary damages under the Federal Tort Claims Act, civil rights statutes, the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, and Texas state law. The bulk of these claims were dismissed because they were insufficient as a matter of law or because the plaintiffs could advance no material evidence in support of them.

The court, after a month-long trial, rejected the Branch Davidians' case. The court found that, on February 28, 1993, the Branch Davidians initiated a gun battle when they fired at federal officers who were attempting to serve lawful warrants.[107] ATF agents returned gunfire to the building, the court ruled, to protect themselves and other agents from death or serious bodily harm. The court found that the government's planning of the siege—i.e., the decisions to use tear gas against the Branch Davidians; to insert the tear gas using military vehicles and to omit specific planning for the possibility that a fire would erupt—was a discretionary function for which the government could not be sued. The court also found that the use of tear gas was not negligent. Further, even if the United States government were negligent by causing damage to the buildings before the fires broke out, thus either blocking escape routes or enabling the fires to spread faster, that negligence did not legally cause the plaintiffs' injuries because the Branch Davidians started the fires.

The Branch Davidians appealed. They contended that the trial court judge, Walter S. Smith, Jr., should have recused himself from hearing their claims on account of his relationships with defendants, defense counsel, and court staff; prior judicial determinations; and comments during trial. The Fifth Circuit concluded that these allegations did not reflect conduct that would cause a reasonable observer to question Judge Smith's impartiality, and it affirmed the take-nothing judgment, in Andrade v. Chojnacki,[108] 338 F.3d 448 (5th Cir. 2003), cert. denied (2004).

Press coverage surrounding the Waco siege

The press coverage of the Waco siege was criticized by some[who?] for its sensationalism and for providing a platform for David Koresh and his followers. Some journalists were accused of glamorizing Koresh and his beliefs, leading to concerns that the media attention may have unintentionally fueled the cult leader's messianic complex and prolonged the standoff. The legal proceedings that followed were complex and involved charges ranging from firearms violations to conspiracy to commit murder. Several surviving Branch Davidians faced trial,[109] and some were convicted and sentenced to lengthy prison terms.[110] However, the trials themselves were also criticized by some[who?] who believed that the defendants that were fueled by the media did not receive a fair trial or that the government failed to fully investigate its own actions during the siege.[citation needed][111]

Controversies

Roland Ballesteros, one of the agents assigned to the ATF door team that assaulted the front door, told Texas Rangers and Waco police that he thought the first shots came from the ATF dog team assigned to neutralize the Branch Davidians' dogs, but later at the trial, he insisted that the Branch Davidians had shot first.[112] The Branch Davidians also claimed that the ATF door team opened fire at the door, and they returned fire in self-defense. An Austin Chronicle article noted, "Long before the fire, the Davidians were discussing the evidence contained in the doors. During the siege, in a phone conversation with the FBI, Steve Schneider, one of Koresh's main confidants told FBI agents that 'the evidence from the front door will clearly show how many bullets and what happened'."[113] Houston attorney Dick DeGuerin, who went inside Mount Carmel during the siege, testified at the trial that protruding metal on the inside of the right-hand entry door made it clear that the bullet holes were made by incoming rounds. DeGuerin also testified that only the right-hand entry door had bullet holes, while the left-hand entry door was intact. The government presented the left-hand entry door at the trial, claiming that the right-hand entry door had been lost. The left-hand door contained numerous bullet holes made by both outgoing and incoming rounds. Texas Trooper Sgt. David Keys testified that he witnessed two men loading what could have been the missing door into a U-Haul van shortly after the siege had ended, but he did not see the object itself.[113] Michael Caddell, the lead attorney for the Branch Davidians' wrongful death lawsuit explained, "The fact that the left-hand door is in the condition it's in tells you that the right-hand door was not consumed by the fire. It was lost on purpose by somebody." Caddell offered no evidence to support this allegation, which has never been proven. However, fire investigators stated that it was "extremely unlikely" that the steel right door could have suffered damage in the fire much greater than did the steel left door, and both doors would have been found together. The right door remains missing, and the entire site was under close supervision by law enforcement officials until the debris—including both doors—had been removed.[113]

In the weeks preceding the raid, Rick Alan Ross, a self-described cult expert and deprogrammer affiliated with the Cult Awareness Network, appeared on major networks such as NBC[114] and CBS in regard to Koresh.[115] Ross later described his role in advising authorities about the Davidians and Koresh, and what actions should be taken to end the siege.[116] He was quoted as saying that he was consulted by the ATF[117] and he contacted the FBI on March 4, 1993, requesting "that he be interviewed regarding his knowledge of cults in general and the Branch Davidians in particular." The FBI reports that it did not rely on Ross for advice whatsoever during the standoff, but that it did an interview and received input from him. Ross also telephoned the FBI on March 27 and March 28, offering advice about negotiation strategies, suggesting that the FBI "...attempt to embarrass Koresh by informing other members of the compound about Koresh's faults and failures in life, in order to convince them that Koresh was not the prophet they had been led to believe."[116] The ATF also contacted Ross in January 1993 for information about Koresh.[116] Several writers have documented the Cult Awareness Network's role about the government's decision-making concerning Waco.[114] Mark MacWilliams notes that several studies have shown how "self-styled cult experts like Ross, anticult organizations like the Cult Awareness Network (CAN), and disaffected Branch Davidian defectors like Breault played important roles in popularizing a harshly negative image of Koresh as a dangerous cult leader. Portrayed as "self-obsessed, egomaniacal, sociopathic and heartless", Koresh was frequently characterized as either a religious lunatic who doomed his followers to mass suicide or a con man who manipulated religion for his own bizarre personal advantage."[118] According to religious scholars Phillip Arnold and James Tabor who made an effort to help resolve the conflict, "the crisis need not have ended tragically if only the FBI had been more open to Religious Studies and better able to distinguish between the dubious ideas of Ross and the scholarly expertise."[119]

In a New Yorker article in 2014, Malcolm Gladwell wrote that Arnold and Tabor told the FBI that Koresh needed to be persuaded of an alternative interpretation of the Book of Revelation, one that does not involve a violent end. They made an audiotape, which they played for Koresh, and which seemed to convince him. However, the FBI waited only three days before beginning the assault, instead of an estimated two weeks for Koresh to complete a manuscript sparked by this alternative interpretation, and then come out peacefully.[120] An article by Stuart A. Wright published in Nova Religio discussed how the FBI mishandled the siege, stating that "there is no greater example of misfeasance than the failure of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to bring about a bloodless resolution to the 51-day standoff."[121] Some of Wright's major concerns about the operation include that the FBI officials, especially Dick Rogers, exhibited increasing impatience and aggression when the conflict could have been resolved by more peaceful negotiation. He mentions that Rogers said in an interview with the FBI that "when we started depriving them, [we were] really driving people closer to him [Koresh] because of their devotion to him,"[121] which was different from what he said in the Department of Justice report.

Attorney General Reno had specifically directed that no pyrotechnic devices be used in the assault. Between 1993 and 1999, FBI spokesmen denied (even under oath) the use of any sort of pyrotechnic devices during the assault; however, pyrotechnic Flite-Rite CS gas grenades had been found in the rubble immediately following the fire. In 1999, FBI spokesmen backtracked, saying that they had in fact used the grenades, but then contended they had only been used during an early morning attempt to penetrate a covered, water-filled construction pit 40 yards (35 m) away and were not fired into the building.[95] As such, the FBI stated that the pyrotechnic devices were unlikely to have contributed to the fire.[95] When the FBI's documents were turned over to Congress for an investigation in 1994, the page listing the use of the pyrotechnic devices was missing. The failure for six years to disclose the use of pyrotechnics, despite her specific directive, led Reno to demand an investigation. A senior FBI official told Newsweek that as many as 100 FBI agents had known about the use of pyrotechnics, but no one spoke up until 1999.[95]

The FBI had planted surveillance devices in the walls of the building, which captured several conversations the government claims are evidence that the Davidians started the fire.[96]: 287 The recordings were imperfect and at many times difficult to understand, and the two transcriptions that were made had differences at many points.[96]: 287 According to reporter Diana Fuentes, when the FBI's April 19 tapes were played in court during the Branch Davidian trials, few people heard what the FBI audio expert claimed to hear; the tapes "were filled with noise, and voices only occasionally were discernible… The words were faint; some courtroom observers said they heard it, some didn't."[122] The Branch Davidians had given ominous warnings involving a fire on several occasions.[123] This may or may not have been indicative of the Branch Davidians' future actions, but was the basis for the conclusion of Congress that the fire was started by the Branch Davidians, "absent any other potential source of ignition." This was before the FBI admission that pyrotechnics were used, but a yearlong investigation by the Office of the Special Counsel after that admission nonetheless reached the same conclusion, and no further congressional investigations followed. During a 1999 deposition for civil suits by Branch Davidian survivors, fire survivor Graeme Craddock was interviewed. He stated that he saw some Branch Davidians moving about a dozen one gallon (3.8 L) cans of fuel so they would not be run over by armored vehicles, heard talk of pouring fuel outside the building, and after the fire had started, something that sounded like "light the fire" from another individual.[124] Professor Kenneth Newport's book The Branch Davidians of Waco attempts to prove that starting the fire themselves was pre-planned and consistent with the Branch Davidians' theology. He cites as evidence the above mentioned recordings by the FBI during the siege, testimonials of survivors Clive Doyle and Graeme Craddock, and the buying of diesel fuel one month before the start of the siege.[96]

The FBI received contradictory reports on the possibility of Koresh's suicide and was not sure about whether he would commit suicide. The evidence made them believe that there was no possibility of mass suicide, with Koresh and Schneider repeatedly denying to the negotiators that they had plans to commit mass suicide, and people leaving the compound saying that they had seen no preparations for such a thing.[79] There was a possibility that some of his followers would join Koresh if he decided to commit suicide.[79] According to Alan A. Stone's report, during the siege the FBI used an incorrect psychiatric perspective to evaluate Branch Davidians' responses, which caused them to over-rely on Koresh's statements that they would not commit suicide. According to Stone, this incorrect evaluation caused the FBI to not ask pertinent questions to Koresh and to others on the compound about whether they were planning a mass suicide. A more pertinent question would have been, "What will you do if we tighten the noose around the compound in a show of overwhelming power, and using CS gas, force you to come out?"[66] Stone wrote:

The tactical arm of federal law enforcement may conventionally think of the other side as a band of criminals or as a military force or, generically, as the aggressor. But the Branch Davidians were an unconventional group in an exalted, disturbed and desperate state of mind. They were devoted to David Koresh as the Lamb of God. They were willing to die defending themselves in an apocalyptic ending and, in the alternative, to kill themselves and their children. However, these were neither psychiatrically depressed, suicidal people nor cold-blooded killers. They were ready to risk death as a test of their faith. The psychology of such behavior—together with its religious significance for the Branch Davidians—was mistakenly evaluated, if not simply ignored, by those responsible for the FBI strategy of "tightening the noose". The overwhelming show of force was not working in the way the tacticians supposed. It did not provoke the Branch Davidians to surrender, but it may have provoked David Koresh to order the mass-suicide.[66]

Danforth's report

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Waco siege" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

The Oklahoma City bombing on April 19, 1995, caused the media to revisit many of the questionable aspects of the government's actions at Waco, and many Americans who previously supported those actions began asking for an investigation of them.[125] By 1999—as a result of certain aspects of the documentaries discussed below, as well as allegations made by advocates for Branch Davidians during litigation, public opinion held that the federal government had engaged in serious misconduct at Waco. A Time poll conducted on August 26, 1999, for example, indicated that 61 percent of the public believed that federal law enforcement officials started the fire at the Branch Davidian complex.

In September 1999, Attorney General Reno appointed former U.S. Senator John C. Danforth as Special Counsel to investigate the matter. In particular, the Special Counsel was directed to investigate charges that government agents started or spread the fire at the Mount Carmel complex, directed gunfire at the Branch Davidians, and unlawfully employed the armed forces of the United States. A yearlong investigation ensued, during which the Office of the Special Counsel interviewed 1,001 witnesses, reviewed over 2.3 million pages of documents, and examined thousands of pounds of physical evidence. In the "Final report to the Deputy Attorney General concerning the 1993 confrontation at the Mt. Carmel Complex, Waco Texas" of November 8, 2000, Special Counsel Danforth concluded that the allegations were meritless. The report found, however, that certain government employees had failed to disclose during litigation against the Branch Davidians the use of pyrotechnic devices at the complex, and had obstructed the Special Counsel's investigation. Disciplinary action was pursued against those individuals.

Allegations that the government started the fire were largely based on an FBI agent's having fired three "pyrotechnic" tear gas rounds, which are delivered with a charge that burns. The Special Counsel concluded that the rounds did not start or contribute to the spread of the fire, based on their finding that the FBI fired the rounds nearly four hours before the fire started, at a concrete construction pit partially filled with water, 75 feet (23 m) away and downwind from the main living quarters of the complex. The Special Counsel noted, by contrast, that recorded interceptions of Branch Davidian conversations included such statements as "David said we have to get the fuel on" and "So we light it first when they come in with the tank right ... right as they're coming in." Some Branch Davidians who survived the fire acknowledged that other Branch Davidians started the fire. FBI agents witnessed Branch Davidians pouring fuel and igniting a fire, and noted these observations contemporaneously. Lab analysis found accelerants on the clothing of Branch Davidians, and investigators found deliberately punctured fuel cans and a homemade torch at the site. Based on this evidence and testimony, the Special Counsel concluded that the fire was started by the Branch Davidians.

Charges that government agents fired shots into the complex on April 19, 1993, were based on forward looking infrared (FLIR) video recorded by the Night Stalkers aircraft. These tapes showed 57 flashes, with some occurring around government vehicles that were operating near the complex. The Office of Special Counsel conducted a field test of FLIR technology on March 19, 2000, to determine whether gunfire caused the flashes. The testing was conducted under a protocol agreed to and signed by attorneys and experts for the Branch Davidians and their families, as well as for the government. Analysis of the shape, duration, and location of the flashes indicated that they resulted from a reflection off debris on or around the complex, rather than gunfire. Additionally, an independent expert review of photography taken at the scene showed no people at or near the points from which the flashes emanated. Interviews of Branch Davidians, government witnesses, filmmakers, writers, and advocates for the Branch Davidians found that none had witnessed any government gunfire on April 19. None of the Branch Davidians who died on that day displayed evidence of having been struck by a high velocity round, as would be expected had they been shot from outside of the complex by government sniper rifles or other assault weapons. Given this evidence, the Special Counsel concluded that the claim that government gunfire occurred on April 19, 1993, amounted to "an unsupportable case based entirely upon flawed technological assumptions."

The Special Counsel considered whether the use of active-duty military at Waco violated the Posse Comitatus Act or the Military Assistance to Law Enforcement Act. These statutes generally prohibit direct military participation in law enforcement functions but do not preclude indirect support such as lending equipment, training in the use of equipment, offering expert advice, and providing equipment maintenance. The Special Counsel noted that the military provided "extensive" loans of equipment to the ATF and FBI, including—among other things—two tanks, the offensive capability of which had been disabled. Additionally, the military provided limited advice, training, and medical support. The Special Counsel concluded that these actions amounted to indirect military assistance within the bounds of applicable law. The Texas National Guard, in its state status, also provided substantial loans of military equipment, as well as performing reconnaissance flights over the Branch Davidian complex. Because the Posse Comitatus Act does not apply to the National Guard in its state status, the Special Counsel determined that the National Guard lawfully provided its assistance.

Ramsey Clark—a former U.S. Attorney General, who represented several Branch Davidian survivors and relatives in a civil lawsuit—said that the report "failed to address the obvious": "History will clearly record, I believe, that these assaults on the Mt. Carmel church center remain the greatest domestic law enforcement tragedy in the history of the United States."[126]

Equipment and manpower

Government agencies

Raid (February 28): 75 federal agents (ATF and FBI); three Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters crewed by 10 Texas National Guard counter-drug personnel as distraction during the raid and filming;[127][128] ballistic protection equipment, fire retardant clothing, regular flashlights, regular cameras (i.e., flash photography), pump-action shotguns and flashbang grenades,[129] 9 mm handguns, 9 mm MP5 submachine guns, 5.56 NATO M16 rifles, a .308 bolt-action sniper rifle.[130]

Siege (March 1 through April 18): Hundreds of federal agents; two Bell UH-1 Iroquois helicopters.[131]

Assault (April 19): Hundreds of federal agents; military vehicles (with their normal weapon systems removed): approx. nine M3 Bradley infantry fighting vehicles, four or five M728 Combat Engineering Vehicles (CEVs) armed with CS gas, two M1A1 Abrams main battle tanks, one M88 recovery vehicle.[128][131]

Support:[128] one Britten-Norman Defender surveillance aircraft;[132] a number of Texas National Guard personnel for maintenance of military vehicles and training on the use of the vehicles and their support vehicles (Humvees and flatbed trucks); surveillance from Texas National Guard counter-drug UC-26 surveillance aircraft and from Alabama National Guard; three soldiers from Delta Force, to serve as observers (also present during assault);[133] two senior U.S. Army officers as advisers, two members of the British Army's 22nd Special Air Service (SAS) Regiment as observers;[134] 50+ men in total.[135]

Branch Davidians

The Branch Davidians were well-stocked with small arms,[135][136] possessing 305 total firearms, including numerous rifles (semi-automatic AK-47s and AR-15s), shotguns, revolvers and pistols;[88][94][137] 46 semi-automatic firearms modified to fire in fully automatic mode (included on above list): 22 AR-15 (erroneously referred to as M16), 20 AK-47 rifles, 2 HK SP-89, 2 M-11/Nine[94][137] Texas Rangers reported "at least 16 AR-15 rifles,";[88] 2 AR-15 lower receivers modified to fire in fully automatic mode;[137] 39 "auto sear" devices used to convert semi-automatic weapons into automatic weapons; parts for fully automatic AK-47 and M16 rifles; 30-round magazines and 100-round magazines for M16 and AK-47 rifles; pouches to carry large ammunition magazines; substantial quantities of ammunition of various sizes.

Other items found at the compound included about 1.9 million rounds of "cooked off" ammunition;[88] grenade launcher parts; flare launchers; gas masks and chemical warfare suits; night vision equipment; hundreds of practice hand grenade hulls and components (including more than 200 inert M31 practice rifle grenades, more than 100 modified M-21 practice hand grenade bodies, 219 grenade safety pins and 243 grenade safety levers found after the fire);[137] Kevlar helmets and ballistic vests; 88 lower receivers for the AR-15 rifle; and approximately 15 sound suppressors or silencers (the Treasury reports lists 21 silencers,[137] Texas Rangers report that at least six items had been mislabeled and were actually 40 mm grenades or flash bang grenades from manufacturers who sold those models to the ATF or FBI exclusively;[138][139] former Branch Davidian Donald Bunds testified he had manufactured silencers under direct orders of Koresh).[140]

The ATF knew that the Branch Davidians had a pair of .50 caliber rifles, so they asked for Bradley fighting vehicles, which could resist that caliber.[141] During the siege, Koresh said that he had weapons bigger than .50 rifles and that he could destroy the Bradleys, so they were supplemented with two Abrams tanks and five M728 vehicles.[141][142] The Texas Rangers recovered at least two .50 caliber weapons from the remains of the compound.[88][94]

Whether the Branch Davidians actually fired the .50 caliber rifles during the raid or the assault is disputed. Various groups supporting gun control, such as Handgun Control Incorporated and the Violence Policy Center, have claimed that the Branch Davidians had fired .50 caliber rifles, and they have cited this as one reason to ban these weapons.[143][144] The ATF claims such rifles were used against ATF agents the day of the search. Several years later, the General Accounting Office, in response to a request from Henry Waxman, released a briefing paper titled "Criminal Activity Associated with .50 Caliber Semiautomatic Rifles" that repeated the ATF's claims that the Branch Davidians used .50 caliber rifles during the search.[145] FBI Hostage Rescue Team snipers reported sighting one of the weapons, readily identifiable by its distinctive muzzle brake, during the siege.[146]

Legacy

Connection to the Oklahoma City bombing

Main article: Oklahoma City bombing

The destroyed Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building

Timothy McVeigh cited the Waco incident as a primary motivation[147] for the Oklahoma City bombing, his 19 April 1995 truck bomb attack that destroyed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, a U.S. government office complex in downtown Oklahoma City, and destroyed or damaged numerous other buildings in the vicinity. The attack claimed 168 lives (including 19 children under age 6) and left over 600 injured in the deadliest act of terrorism on U.S. soil before the September 11 attacks. As of 2024, it remains the deadliest act of domestic terrorism in American history.[a]

Within days after the bombing, McVeigh and Terry Nichols were both taken into custody for their roles in the bombing. Investigators determined that the two were both sympathizers of an anti-government militia movement and that their motive was to avenge the government's handling of the Waco and Ruby Ridge incidents.[148] McVeigh testified that he chose the date of April 19 because it was the second anniversary of the deadly fire at Mount Carmel. In March 1993, McVeigh drove from Arizona to Waco to observe the federal standoff. Along with other protesters, he was photographed by the FBI,[149] and McVeigh himself was briefly interviewed by a television reporter. A courtroom reporter also claims to have later seen McVeigh outside the courthouse at Waco, selling anti-government bumper stickers.[150]

Other events sharing the date of fire at Mt. Carmel have been mentioned in discussions of the Waco siege. The April 20, 1999, Columbine High School massacre might have been timed to mark either an anniversary of the FBI's assault at Waco or Adolf Hitler's birthday.[151] Some of the connections appear coincidental.[152] Eight years before the Waco fire, the ATF and FBI raided another compound of a religious cult: The Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord. Some ATF agents who were present at that raid were present at Waco. April 19 was also the date from the American Revolution's opening battles of Lexington and Concord.

Montana Freeman siege

The Montana Freemen became the center of public attention in 1996 when they engaged in a prolonged armed standoff with agents of the FBI. The Waco siege, as well as the 1992 incident between the Weaver family and the FBI at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, were still fresh in the public mind, and the FBI was extremely cautious and wanted to prevent a recurrence of those violent events.[153] After 81 days of negotiations, the Freemen surrendered to authorities on June 14, 1996 without a loss of life.[154]

Media portrayals of Waco

The Waco siege has been the subject of numerous documentary films and books. The first film was a made-for television docudrama film, In the Line of Duty: Ambush in Waco, which was made during the siege, before the April 19 assault on the church, and presented the initial firefight of February 28, 1993 as an ambush. The film's writer, Phil Penningroth, has since disowned his screenplay as pro-ATF "propaganda".[155]

Books

The first book about the incident was 1993's Inside the Cult co-authored by ex-Branch Davidian Marc Breault, who left the group in September 1989, and Martin King who interviewed Koresh for Australian television in 1992. In July 1993, true crime author Clifford L. Linedecker published his book Massacre at Waco, Texas.

Shortly after, in 1994, a collection of 45 essays called From the Ashes: Making Sense of Waco was published, about the events of Waco from various cultural, historical, and religious perspectives. The essays in the book include one by Michael Barkun that talked about how the Branch Davidians' behavior was consistent with other millenarian religious sects and how the use of the word cult is used to discredit religious organizations, one by James R. Lewis that claims a large amount of evidence that the FBI lit the fires, and many others. All of these perspectives are united in the belief that the deaths of the Branch Davidians at Waco could have been prevented and that "the popular demonization of nontraditional religious movements in the aftermath of Waco represents a continuing threat to freedom of religion".[156]

Carol Moore's The Davidian Massacre: Disturbing Questions About Waco That Must Be Answered was published in 1995.

The American novelist John Updike has been directly inspired by the Waco events for the fourth and last part of his book In the Beauty of the Lilies (1996) which described how a troubled child could integrate such a sect and the inner dynamics that led to a collective massacre.[157]

Documentaries

The first documentary films critical of the official versions were Waco, the Big Lie[158] and Waco II, the Big Lie Continues, both produced by Linda Thompson in 1993. Thompson's films made several controversial allegations, the most notorious of which was her claim that footage of an armored vehicle breaking through the outer walls of the compound, with an appearance of orange light on its front,[159] was showing a flamethrower attached to the vehicle, setting fire to the building. As a response to Thompson, Michael McNulty released footage to support his counter-claim that the appearance of light was a reflection on aluminized insulation that was torn from the wall and snagged on the vehicle. (The vehicle is an M728 CEV, which is not normally equipped with a flamethrower.[160]) McNulty accused Thompson of "creative editing" in his film Waco: An Apparent Deviation. Thompson worked from a VHS copy of the surveillance tape; McNulty was given access to a beta original. However, McNulty in turn was later accused of having digitally altered his footage, an allegation he denied.[161]

The next film was Day 51: The True Story of Waco, produced in 1995 by Richard Mosley and featuring Ron Cole, a self-proclaimed militia member from Colorado who was later prosecuted for weapons violations.[162] Thompson's and Mosley's films, along with extensive coverage given to the Waco siege on some talk radio shows, galvanized support for the Branch Davidians among some sections of the right, including the nascent militia movement, while critics on the left also denounced the government siege on civil liberties grounds. In 2000, radio host and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones made a documentary film, America Wake Up (Or Waco), about the government's purported role in the siege.[163]

In 1997, filmmakers Dan Gifford and Amy Sommer produced their Emmy Award-winning documentary film, Waco: The Rules of Engagement,[64] presenting a history of the Branch Davidian movement and a critical examination of the conduct of law enforcement, both leading up to the raid and through the aftermath of the fire. The film features footage of the Congressional hearings on Waco, and the juxtaposition of official government spokespeople with footage and evidence often directly contradicting the spokespeople. In the documentary, Dr. Edward Allard (who held patents on FLIR technology) maintained that flashes on the FBI's infra-red footage were consistent with a grenade launcher and automatic small arms fire from FBI positions at the back of the complex toward the locations that would have provided exits for Branch Davidians attempting to flee the fire. Waco: The Rules of Engagement was nominated for a 1997 Academy Award for best documentary and was followed by another film in 1999, Waco: A New Revelation.[164]

In 2001, another Michael McNulty documentary, The F.L.I.R. Project, researched the aerial thermal images recorded by the FBI, and using identical FLIR equipment recreated the same results as were recorded by federal agencies April 19, 1993. Subsequent government-funded studies[165] contend that the infra-red evidence does not support the view that the FBI improperly used incendiary devices or fired on Branch Davidians. Infra-red experts continue to disagree and filmmaker Amy Sommer stands by the original conclusions presented in Waco: The Rules of Engagement.

The documentary The Assault on Waco was first aired in 2006 on the Discovery Channel, detailing the entire incident. A British-American documentary, Inside Waco, was produced jointly by Channel 4 and HBO in 2007, attempting to show what happened inside by piecing together accounts from the parties involved. The MSNBC documentary Witness to Waco: Inside the Siege was released in 2009.[166]

A Netflix documentary series called Waco: American Apocalypse, was released in March 2023. The series encompasses three episodes and features real and never before released footage and interviews with surviving cult members along with others involved.[167]

Dramatizations

In 2018, the miniseries Waco premiered on Paramount Network, dramatizing both the Waco siege and the 1992 siege at Ruby Ridge. It received mixed reviews, with critics praising the direction and performances but criticizing the show's overly sympathetic portrayal of David Koresh.[168][169][170]

Songs

Grant Lee Buffalo's 1994 album Mighty Joe Moon opening track "Lone Star Song" directly references the siege.[171]

Two heavy metal bands wrote songs about the Davidian standoff: Machine Head's "Davidian" opened their debut album Burn My Eyes[172] and Sepultura’s "Amen" was the fourth track from their Chaos A.D. album.[173] Native American activist Russell Means included a song about the siege on his 2007 album The Radical, titled "Waco: The White Man's Wounded Knee".[174]

Hip hop duo Heavy Metal Kings, featuring Vinnie Paz of Jedi Mind Tricks and Ill Bill, reference the siege in their song Impaled Nazarene from their 2011 self-titled debut. Ill Bill recounts Koresh's story, portraying him in a positive light.[175] The track ends with an audio clip of Koresh talking as the music fades out over the last moment. Jedi Mind Tricks has a history of incorporating mysticism and conspiracy theories into his music, and he also incorporated them into the song Blood In Blood Out from the 2003 album Visions of Gandhi raps "I like blood/ I like tastin' ya flesh/ I like slugs/ I like David Koresh."[176]

Also in 2011, British indie rock band The Indelicates released a concept album, David Koresh Superstar, about Koresh and the Waco siege.[177][178]

Video games

The map Oregon from the tactical shooter Rainbow Six Siege, developed and published by Ubisoft, bears a similarity to the Mount Carmel Center.[179] Despite the fact that it has not been confirmed by the developers, it has also been seen as a source of inspiration for the map's setting, because the main building closely resembles the Davidians' church. While the map does not include the entire compound, comparing the two bears a striking resemblance to the original compound.[180]

One of the errands on Friday in the first-person shooter Postal 2, requires the player to deliver a package to their Uncle Dave at his compound, which is later revealed to be under siege by the ATF, which informs Uncle Dave's cult to douse themselves in something "flammable" and gather together in a confined space. Later on, one of the ATF agents engulfs the compound in flames with a Napalm launcher. The compound's appearance bears a striking, almost verbatim appearance to Mount Carmel Center.

Xatrix Entertainment's 1998 video game, Redneck Rampage Rides Again contains a reference to the siege in one of the game's maps titled "Wako", where the player has the ability to blow up the compound.

Series

The Waco siege is used as a subplot in the episode “Two Guys Naked in a Hot Tub” of South Park S3E8. In the episode the ATF plans to save the day by stopping the ‘cultists’ of a meteor-shower from killing themselves. Even if it means they have to “Kill every single one of them”. The episode depicted the ATF as incompetent and shows them killing multiple innocent people needlessly.[181]

Personal accounts

Branch Davidian survivor David Thibodeau wrote his account of life in the group and of the siege in the book A Place Called Waco, published in 1999. His book served in part as the basis for the 2018 Paramount Network six-part television drama miniseries Waco, starring Michael Shannon as the FBI negotiator Gary Noesner, Taylor Kitsch as David Koresh, and Rory Culkin as Thibodeau.[182][183] Developed by John Erick Dowdle and Drew Dowdle, it premiered on January 24, 2018.

The City of God: A New American Opera by Joshua Armenta dramatized the negotiations between the FBI and Koresh, premiered in 2012, utilizing actual transcripts from the negotiations as well as biblical texts and hymns from the Davidian hymnal.[184] In 2015, Retro Report released a mini documentary looking back at Waco and how it has fueled many right-wing militias.[185]

The Mount Carmel site today

Today, the site where the Mount Carmel Center sat is occupied by a church built directly atop where the cult building used to be. It is still used by the remaining Branch Davidians as a place of worship and memorial. A memorial plaque for the four ATF agents killed in the shootout is on the grounds as is the barbed wire the authorities used to prevent the cult members from escaping.[186]

See also

icon1990s portalflagUnited States portaliconPolitics portalflagTexas portal

In the United States

Alamo Christian Foundation

Critical Incident Response Group of the FBI, formed in response to the incident

Heaven's Gate (religious group), 1997

Peoples Temple

Jonestown

Ken Ballew raid, 1971

Miracle Valley shootout, Arizona, 1982

Montana Freemen, 1996

1985 MOVE bombing, Philadelphia, 1985 siege

Oklahoma City bombing, Oklahoma City, April 19, 1995, on the second anniversary of the end of the Waco Siege

Rainbow Farm, Michigan, 2001

Ruby Ridge, Idaho, 1992

Shannon Street massacre, Memphis, Tennessee, 1983

YFZ Ranch, located near Eldorado in Schleicher County, Texas

Morrisite War, 1862, government siege of a religious group.

International

Grand Mosque Seizure, Mecca, Saudi Arabia, 1979

Operation Blue Star, Golden Temple, Amritsar, India, 1984

Memali siege, Kedah, Malaysia, 1985

Order of the Solar Temple, 1994

2000 Uganda cult massacres, Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God, Uganda, 2000

Siege of Lal Masjid, Pakistan, 2007

August 2013 Rabaa massacre, Egypt, 2013

Arrest of Sant Rampal, India, 2014

Shakahola Forest incident, Kilifi County, Kenya, 2023

Notes

Prior to 9–11, the deadliest act of terror against the United States was the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, which killed 189 Americans.

References

Report of the Department of the Treasury on the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms Investigation of Vernon Wayne Howell Also Known as David Koresh, September 1993 Archived April 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, PDF of actual report, p. 8.

O'Hanlon, Ray (February 16, 2011). "Inside File: SAS at Waco, too". Irish Echo. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

River, Charles (2018). The Special Air Service: The History of the Secret British Special Forces Unit from World War II to Today. Charles River Editors. p. 60.

Report of the Department of the Treasury on the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms Investigation of Vernon Wayne Howell Also Known as David Koresh. the Department. September 1993. pp. 51, 77. ISBN 9780160242052. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

"Survivors of 1993 Waco siege describe what happened in fire that ended the 51-day standoff". ABC News. January 3, 2018. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2022. The article publicized an ABC documentary "Truth and Lies: Waco" broadcast on January 4. The article states "about 80 people, including more than 20 children, died in the fire. Only nine people survived." It also states that there were 46 children inside the compound at the start of the siege, 21 of whom were released during the first five days of negotiations.

"25 Years After The Tanks, Tear Gas And Flames, 'Waco' Returns To TV". National Public Radio. January 23, 2018. Archived from the original on January 28, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2022. The article features an interview with FBI negotiator Gary Noesner. The article states "35 people out through the negotiation process, including 21 children."

Zarrell, Matt (December 27, 2017). "U.S. NEWS UPS driver still haunted over role in Waco massacre nearly 25 years later". Daily News. Archived from the original on May 29, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

Pearson, Muriel; Wilking, Spencer; Effron, Lauren (January 3, 2018). "Survivors of 1993 Waco siege describe what happened in fire that ended the 51-day standoff". ABC News. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

Burton, Tara Isabella (April 19, 2018). "The Waco tragedy, explained". Vox. Archived from the original on April 23, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

"25 years after the Waco massacre, a DO remembers the fire and the victims". The DO. April 16, 2018. Archived from the original on July 25, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

Justin Sturken; Mary Dore (February 28, 2007). "Remembering the Waco Siege". ABC News. Archived from the original on August 3, 2008. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

Wright, Stuart A. (1995). Armageddon in Waco: Critical Perspectives on the Branch Davidian Conflict. University of Chicago Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-226-90844-1.

Smyrl, Vivian Elizabeth (June 12, 2010). "Elk, Texas". Handbook of Texas – Texas State Historical Association. Archived from the original on June 5, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

Ames, Eric S (2009). Images of America WACO. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-7131-7.

Dick J. Reavis, The Ashes of Waco: An Investigation (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), p. 13 Archived March 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 0-684-81132-4

Gennaro Vito, Jeffrey Maahs,Criminology: Theory, Research, and Policy, Edition 3, revised, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2011, ISBN 0763766658, 978-0763766658, p. 340 Archived March 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

"Report to the Deputy Attorney General on the Events at Waco, Texas: Appendix D. Arson Report". www.justice.gov. September 15, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

"FBI chief hails new Waco report". CNN.com. CNN. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

"Waco - The Inside Story". pbs.org. PBS. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

"The Waco tragedy, explained". Vox.com. April 19, 2018.

"The Real Story Behind the Waco Siege: Who Were David Koresh and the Branch Davidians?". Time.com. January 24, 2018.

"What Really Happened At Waco". CBS News. January 25, 2000.

"Timothy McVeigh in Waco". Retrieved March 19, 2023.

Niebuhr, Gustav (April 26, 1995). "Terror in Oklahoma: Religion; Assault on Waco Sect Fuels Extremists' Rage". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 18, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

"Scholars tackle "cult" questions 20 years after Branch Davidian tragedy". WacoTrib.com: Religion. April 13, 2013. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

Psychotherapy Networker, March/April 2007, "Stairway to Heaven; Treating children in the crosshairs of trauma." Excerpt from the book The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog by Bruce Perry and Maia Szalavitz.

New, David S. (2012). Christian Fundamentalism in America: A Cultural History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 182.

"Adventists kicked out cult, leader". Chicago Tribune. March 1993. "After spending two years regrouping in Palestine, Texas, Koresh returned to Mt. Carmel ..."

Jordan Bonfante in Los Angeles; Sally B. Donnelly in Waco; Michael Riley in Waco; Richard N. Ostling in New York (March 15, 1993). "Cult of Death". Time magazine. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved November 1, 2010. "It ended with Howell being driven from the sect at gunpoint. He briefly established his own congregation, living with them in tents and packing crates in nearby Palestine, Texas."

"Waco Siege". HISTORY. December 19, 2017. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

Clifford L. Linedecker, Massacre at Waco, Texas, St. Martin's Press, 1993, pp. 70–76. ISBN 0-312-95226-0.

England, Mark (April 21, 1988). "Judge rules casket out as evidence on Roden". WacoTrib.com. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

Witherspoon, Tormy (January 28, 1989). "District judge throws out Roden's leadership lawsuit". WacoTrib.com. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

Institute, Christian Research (April 14, 2009). "The Branch Davidians". Christian Research Institute. Retrieved June 5, 2024.

Marc Breault and Martin King, Inside the Cult, Signet, 1993, ISBN 978-0-451-18029-2. (Australian edition entitled Preacher of Death).

"Why Waco? Cults and the Battle for Religious Freedom in America" (PDF). Tabor, James D., and Gallagher, Eugene V. January 1, 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

Fantz, Ashley. "Who was David Koresh?". Edition.cnn.com. Archived from the original on April 19, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

Clifford L. Linedecker, Massacre at Waco, Texas, St. Martin's Press, 1993, p. 94. ISBN 0-312-95226-0.

Ten years after Waco, People Weekly, April 28, 2003

England, Mark, and Darlene McCormick. "The Sinful Messiah: Part One", Waco Tribune-Herald, February 27, 1993, pages 1A, 10A, and 11A.

Sant, Peter van (April 14, 2018). ""I've kept my story secret for the last 25 years -- I didn't want to take this to my grave"". CBS News. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

s:Activities of Federal Law Enforcement Agencies Toward the Branch Davidians/Section 2|Activities of Federal Law Enforcement Agencies Toward the Branch Davidians: II. The ATF Investigation.

Higgins, Steve (July 2, 1995). "The Waco Dispute – Why the ATF Had to Act". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

Neil Rawles (February 2, 2007). Inside Waco (Television documentary). Channel 4/HBO.

Marc Smith, "Agent allegedly refused Koresh's offer," Houston Chronicle, September 11, 1993; "Gun Dealer Alerted Koresh to ATF Probe, Lawyer Says," Houston Post, Associated Press, September 11, 1993.

Henry McMahon, Testimony, 1995 Congressional Hearings on Waco, part 1, pp. 162–63. Stuart H. Wright, Editor of Armageddon at Waco, and Robert Sanders, former ATF Deputy Director, also remarked on the ATF refusal of Koresh's offer in testimony.

Darlene McCormick, "Sheriff says he did not curb probe," Waco Tribune-Herald, October 10, 1993.

"Tripped Up By Lies: A report paints a devastating portrait of ATF's Waco planning – or, rather, the lack of it" Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Time, October 11, 1993.

Aguilera, Davy; Green, Dennis G. (February 25, 1993). "The Waco Affidavit". US District Court for the Western District of Texas - Waco. Archived from the original on October 2, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2019 – via Constitution Society.

This Is Not An Assault: Penetrating the Web of Official Lies Regarding the Waco Assault. Xlibris Corporation. May 29, 2001. ISBN 9781465315571. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

Search Warrant W93-15M for the "residence of Vernon Wayne Howell, and others", signed by U.S. Judge or Magistrate Dennis G. Green, dated 25 February 1993 8:43 pm at Waco, Texas

Theodore H. Fiddleman; David B. Kopel (June 28, 1993). "ATF's basis for the assault on Waco is shot full of holes – Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms fatal attack on the Branch Davidian complex in Waco, Texas – Column". Insight on the News. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2008 – via FindArticles.

Cohen, W. S.; Reno, J. F.; Summers, L. H. (August 26, 1999). "Military Assistance Provided at Branch Davidian Incident" (PDF). Report to the Secretary of Defense, the Attorney General, and the Secretary of the Treasury. United States General Accounting Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

Thomas R. Lujan, "Legal Aspects of Domestic Employment of the Army Archived January 27, 2018, at the Wayback Machine," Parameters U.S. Army War College Quarterly, Autumn 1997, Vol. XXVII, No. 3.

Eric Christensen (June 18, 2001). "Reno's halfway house". Insight on the News. Archived from the original on August 17, 2009. Retrieved March 30, 2008 – via FindArticles.

Report of the Department of the Treasury on the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms Investigation of Vernon Wayne Howell Also Known as David Koresh, September 1993 Archived April 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, PDF of actual report, pp. 9–10.

Report of the Department of the Treasury on the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms Investigation of Vernon Wayne Howell also known as David Koresh, September, 1993 Archived April 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, pp. 136–40.

Albert K Bates (Summer 1995). "Showtime At Waco". Communities Magazi

-

6:37:17

6:37:17

The Memory Hole

2 months agoNixon Impeachment Hearings Day 6 (1974-07-29)

648 -

LIVE

LIVE

Major League Fishing

23 hours agoLIVE MLF College Fishing Championship!

331 watching -

2:08:32

2:08:32

Tim Pool

4 hours agoAmerica First or Supporting Ukraine War, DEBATE | The Culture War with Tim Pool

155K176 -

59:04

59:04

Ben Shapiro

2 hours agoEp. 2178 - SHOWDOWN: Trump Stares Down China

28.1K19 -

1:39:05

1:39:05

Steven Crowder

5 hours ago🔴 Doge's Big Secret & Trump Slaps Commies and Illegals

373K249 -

LIVE

LIVE

Canada Strong and Free Network

7 hours agoCanada Strong and Free Network

337 watching -

DVR

DVR

Rebel News

2 hours ago $1.57 earnedLibs push more censorship, Carney's ties to 'largest tax scam', CCP influence in BC | Rebel Roundup

17.9K7 -

58:27

58:27

The Big Mig™

2 hours agoTITLE: Global Finance Forum From Bullion To Borders We Cover It All

18.5K3 -

50:13

50:13

The Rubin Report

6 hours agoWill Trump’s New Escalation in Trade War with China Backfire?

94.6K20 -

1:25:20

1:25:20

Flyover Conservatives

14 hours agoFrom Stuck to Scaling: Clay Clark’s 5 Tips to Rapid Business Growth - Clay Clark | FOC Show

29.3K4