Premium Only Content

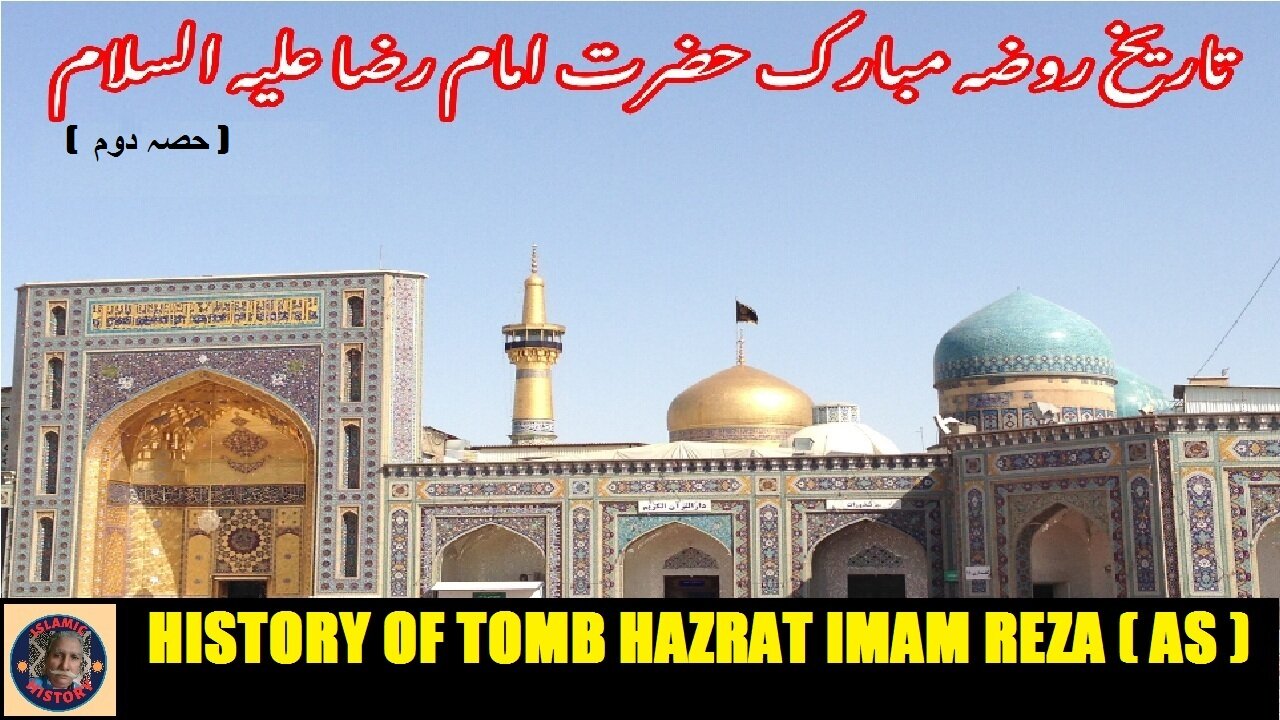

Part-2 History of shrine of Hazrat Imam Reza (AS) روضہ حضرت امام رضا علیہ السلام کی تاریخ

@islamichistory813 #ImamReza #ShrineHistory #IslamicHeritage

History of shrine of Imam Reza (AS).

Part-2

Asslamoalaikum sisters brothers friends and elders We are describing remaining history in this islamic informative about holiest sties video provides a comprehensive overview of the history of the shrine of Imam Reza, tracing its origins and development over the centuries. Viewers will gain insight into the significance of this sacred site within the context of Islamic history and its enduring importance to followers of the faith.

While the site has been considered a locus of pilgrimage since the death of the Imam, Farmanfarmaian argues that Shah Abbas began promoting the site in order to “deflect the flow of pilgrims and their money from the more important shrines of Ottoman-controlled Iraq.” Abass’ attention to Mashhad reflects a desire to legitimate Iran as a Muslim Shi’i power on the international stage and to challenge the prestige of the Ottoman Caliphate, despite their control over major holy sites like Mecca, Medina, Karbala, and Najaf.

Like Shah Abbas, Aqa Mohammad Khan Qajar is said to have walked barefoot to the tomb of Imam Reza in 1796, where he spent twenty days in the Haram praying and working as a servant. This act of piety is significant, because it reflects the importance of properly engaging in an act of worship for their own sakes. Aqa Mohammad Khan Qajar, like other rulers before and after him, may have believed that without properly going on pilgrimage, his rule would not be given divine blessing. In fact, similar reasons could be given for Shah Abbas’ decision to embark on a similar pilgrimage two centuries prior. Such intensive acts must be considered beyond their public value, since they go above and beyond a general effort to gain political legitimacy. Perhaps these shahs were seeking Imam Reza’s approval as rulers of the sole Shi’i empire of their eras.

Of course, such acts are not necessarily bereft of any political value. When Aqa Mohammad Khan Qajar made his pilgrimage, he had recently taken Mashhad from Shahrukh Shah, the grandson of Nader Shah Afshar, in 1796. By visiting Mashhad personally, Aqa Mohammad Khan Qajar was able to establish himself amongst the city natives who knew little about the new king.

Aqa Mohammad Shah Qajar was succeeded by his nephew, Fat’h ‘Ali Shah who continued to expand the Qajar state. Mashhad had been the capital of the short-lived Afsharid Empire, and although Shahrukh Khan had been defeated, it remained a stronghold of the Afsharids until Fat’h ‘Ali Shah launched two prolonged sieges on Mashhad and drive out the last of the remaining Afsharids. The sieges, undoubtedly, devastated the city, and Fat’h ‘Ali Shah began a program of reconstruction and expansion for the Haram complex. The New Courtyard was one such addition.

Looking to establish their power independently of ulema control, the Qajars supported forms of popular Shi’i culture that were less driven by texts but instead on local traditions, thus placing them beyond the realm of clerical authority. These included taziyeh performances and the rebuilding of shrines. Qajar support for Shi’i shrines included the funding for repairs and general maintenance of Shi’i shrines or mosques in even the Ottoman Empire, especially those in Karbala and Najaf. Naturally, the Qajars paid special attention to the maintenance and expansion of the Imam Reza Shrine, as the most important Shi’i site under their jurisdiction.

And so, these additions continued with subsequent Qajar kings. In 1861, Nasir al-Din Shah renovated the ivan leading into the shrine chamber from the New courtyard by covering it with gold. It is now accurately known as the Ivan-i Talai-e Nasiri, or the “Nasiri Golden Ivan.” Nasir al-Din Shah also ordered the installation of masterful ayeneh kari or “mirror-work” in the shrine, covering earlier Safavid-era decorative pieces with mosaic-like mirrored patterns. Mirror-work became a distinctly Iranian art, famously associated with the Imam Reza Shrine.

During the late Qajar period, the majority of those employed in the shrine received their salaries by the state. Thus, the shrine was not used for revolutionary purposes or bast. This was unusual in relation to other mosques and shrines across the country, which were host to a wide variety of political activities during the Tobacco Revolt in 1890 and Constitutional Revolution in 1906-11.

Pahlavi Era: Modernizing Sacred Space

Reza Shah came to power in 1925, and almost immediately embarked upon a series of reforms to Westernize and modernize Iran. The most famous of these reforms were the laws banning traditional dress, including women’s veil in the 1930s. Although the debate raged all over the country, due to the Shrine’s unique importance as a spiritual center, it became the site of a decisive confrontation between religious leaders and the authorities. It was especially important in the context of the shrine because kashf-e hejab, which prohibited women from covering their hair, had important implications for pilgrims. How were women to dress in the sacred space?

The Gohar Shad mosque became a site for members of the ulema to discuss Reza Shah’s dress code decrees. Ultimately, the Pahlavi government decided that scarves were illegal, but hats were not. The ulema reacted negatively to these new policies, and eventually took up bast (refuge) in the mosque. On July 13th 1935, government forces entered the site and fired at protesters, killing dozens. In 1936, a similar question arose, this time regarding Muslim women pilgrims from India and Afghanistan, and an understanding was reached they would be permitted to veil, as long as it was not in the traditional Iranian style with a black chador.

The drive towards modernization would target the shrine in much bigger ways under the reign of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who succeeded his father in 1941. The complex was dramatically changed during this period of time, and entire neighborhoods around the complex were completely demolished by Mohammad Reza Shah in the 1960s, dramatically altering both the shape and experience of the shrine.

Whereas prior to the demolitions the shrine was part and parcel of Mashhad’s urban fabric and was embedded in the very geography of the place, the destruction caused by planning authorities led to its monumentalization and isolated it from the surrounding city. This made political mobilization difficult in the complex, since there was no entry or escape that could not be monitored by authorities– in stark contrast to major mosques in almost every other city.

Furthermore, it cut the shrine off from the daily life of Mashhadis, making it primarily a structure for tourism and for visiting but one removed from daily life. By isolating the sacred even while seemingly highlighting it as the heart of the city, the Shah’s government also made a clear statement about the distinct division between daily life, which should be secular, and the private realm of the religious. The Shah’s “modern Mashhad” (located further to the northwest) was oriented away from the complex and does not take the shrine as its main reference point.

These changes allowed for the shrine to remain relatively quiet during much of the reign of Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, but the site once again became a place of discontent during the 1979 Revolution.

So friends today we are stoping to describe history of Shrine Imam Reza (AS) here and remaining history will be described in third part InshaAllah tomorow same time. Allah Hafiz.

===========================

-

36:13

36:13

The Why Files

1 month agoAlien Implants Vol. 1: Devil’s Den UFO Encounter: What Was Found Inside Terry Lovelace?

31.7K34 -

4:23:49

4:23:49

FreshandFit

11 hours agoIsrael v Palestine Debate! Respect A Man If He Says No Or Yes To A Girl's Trip?

147K163 -

2:05:33

2:05:33

TheSaltyCracker

13 hours agoTech Bros try to Hijack MAGA ReeEEeE Stream 12-27-24

276K486 -

2:01:25

2:01:25

Roseanne Barr

18 hours ago $38.56 earnedJeff Dye | The Roseanne Barr Podcast #80

125K65 -

7:32

7:32

CoachTY

15 hours ago $11.74 earnedWHALES ARE BUYING AND RETAIL IS SELLING. THIS IS WHY PEOPLE STAY BROKE!!!

114K8 -

1:01:00

1:01:00

Talk Nerdy 2 Us

12 hours ago💻 From ransomware to global regulations, the digital battlefield is heating up!

36.1K1 -

3:00:24

3:00:24

I_Came_With_Fire_Podcast

15 hours agoHalf the Gov. goes MISSING, Trump day 1 Plans, IC finally tells the Truth, Jesus was NOT Palestinian

82.3K33 -

4:11:49

4:11:49

Nerdrotic

17 hours ago $40.96 earnedThe Best and Worst of 2024! Sony Blames Fans | Batman DELAYED | Nosferatu! |Friday Night Tights 334

201K33 -

7:55:51

7:55:51

Dr Disrespect

21 hours ago🔴LIVE - DR DISRESPECT - WARZONE - SHOTTY BOYS ATTACK

244K33 -

1:30:23

1:30:23

Twins Pod

20 hours agoHe Went From MARCHING With BLM To Shaking Hands With TRUMP! | Twins Pod - Episode 45 - Amir Odom

154K34