Premium Only Content

1936/07/30 - Philadelphia Athletics at Chicago White Sox

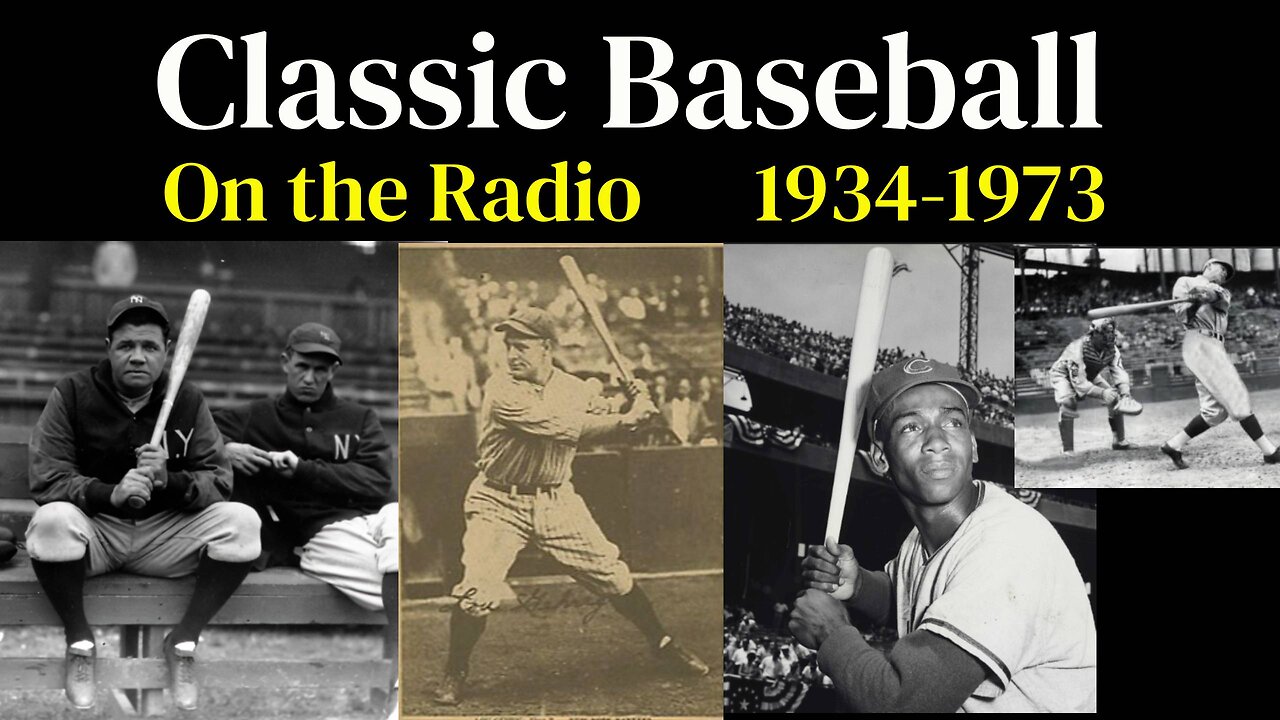

You’re listening to radio broadcast of baseball from 1934 – 1973.

All the greats from the past can be heard in play-by-play action. You’ll hear All-Star games from the 30s as well as individual games of your favorite teams.

Baseball stormed into the 1930s on a voracious high, riding high-speed momentum on the field and on the bottom line; as the fans were thrilled by the boom in offense, the front office was similarly elated by the explosion in profits.

But outside events would slam the brakes on the game’s go-go mentality. The stock market crashed at the end of 1929—sending stocks on a downward spiral that bottomed out in 1932 with a Dow Jones Industrial Average not of 10,000 or 1,000, but 40. Unemployment shot up to 25%, and the only housing growth that seemed to be taking place was those of the shantytowns, makeshift encampments for the many out of work.

The American League continued to deliver all-out offense, propelled by its abundance of hitting stars led by Jimmie Foxx, Lou Gehrig, Hank Greenberg, Earl Averill and Charlie Gehringer. The only AL pitcher who seemed constantly capable of figuring out the hitters was unstoppable ace Lefty Grove.

Meanwhile, the National League—after cranking out an over-the-top batting binge in 1930—muted the hit parade and gave pitchers the equilibrium they’d been desperately seeking since the end of the dead ball era. The NL’s biggest stars of the decade lived on the mound: The colorful, controversial Dizzy Dean, and quiet screwball artist Carl Hubbell.

World War II stripped many of the game’s greats of up to four years of their prime in baseball. If not for armed conflict, Ted Williams—arguably the best pure hitter the game has ever seen—might have finished his career with 3,200 hits and 650 home runs. Warren Spahn, the game’s most productive southpaw, quite possibly would have topped 400 wins. Bob Feller, armed with a supersonic fastball, could have won 300 games, and struck out 3,500. Hank Greenberg might have joined the 500-home run club, while Washington’s Mickey Vernon could have made it to 3,000 hits. But from the heart and to a man, every ballplayer would have considered such a relatively trivial loss of statistics as a small sacrifice compared to helping America defeat the Axis powers.

The Yankees, along with their two brothers of New York baseball—the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants—owned major league baseball for much of the 1950s. Through the decade’s first seven years, every World Series winner represented Gotham—as did five of its losers. There has been great debate over what era of baseball is most rightfully represented as the game’s Golden Age, and if you were loyalists for any one of the three New York-based teams, it was easy to believe this period was it.

It was hardly a Golden Age outside of New York’s city limits. Attendance dropped through much of the 1950s, the blame for which was placed on everything from aging ballparks in decaying inner cities to television to Elvis. The lack of competitive balance that resigned many teams to concede their pennant hopes on Opening Day had something to do with it as well.

Early in the 1960s, 1950s-style baseball was still in charge. The Yankees continued to win pennants. Home whites and road grays remained in vogue. Ted Williams, Warren Spahn and Stan Musial were still producing.

But America of the 1960s evolved into a decade of quick change, if not complete metamorphosis. America’s internal and external problems —and the counterculture that spawned as a result—made major league baseball, the bastion of tradition for over 60 years, feel odd and out-of-place throughout the decade.

Answering to immense pressure, each league reluctantly expanded from eight teams to 10 early in the decade—and more contentedly added two more in 1969 to total 12. The relocations of the Dodgers and Giants to the West Coast at the end of the 1950s were just the beginning of an inevitable trend that would reach all corners of America—and beyond. By the end of the decade, the U.S. Northeast—the long-anchoring region of baseball—saw its geographic power diluted with new or relocated teams in San Diego, Seattle, Minneapolis, Atlanta, Houston and even Montreal in neighboring Canada.

-

LIVE

LIVE

Right Side Broadcasting Network

6 hours agoLIVE: President Trump Delivers Remarks at The White House Digital Assets Summit - 3/7/25

8,327 watching -

2:07:17

2:07:17

The Quartering

3 hours agoTrump Goes Ballistic On Russia & Ukraine Gets Results, Democrat Cringe, FBI Arrests Military Men

41.1K9 -

LIVE

LIVE

Sean Unpaved

2 hours agoWhat Could The 2025 NFL Draft & Season Look Like with Special Guest 2x Super Bowl Champ Phil Simms

628 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

Tactical Advisor

19 minutes agoThe Vault Room Podcast 010 | Huge Health Change/Daniel Defense PCC

106 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

In The Litter Box w/ Jewels & Catturd

20 hours agoTRUMP HOLDS DEMS ACCOUNTABLE | In the Litter Box w/ Jewels & Catturd – Ep. 757 – 3/7/2025

5,074 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

Vigilant News Network

1 hour agoGlobalist TAKEOVER? BlackRock Buying Panama Canal for $22.8 BILLION | The Daily Dose

434 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

Crypto Power Hour

8 hours ago $0.19 earnedThe Crypto Power Hour - ‘In Crypto We Trust’ DC Crypto Summit

121 watching -

UPCOMING

UPCOMING

Mally_Mouse

1 hour agoLet's Play!! -- Jak 2! pt. 6

2.71K -

2:04:21

2:04:21

Tim Pool

5 hours agoAmerica's Obesity & Health Crisis, MAKE AMERICA HEALTHY AGAIN | The Culture War with Tim Pool

95.9K39 -

1:00:20

1:00:20

The Tom Renz Show

3 hours agoCDC Will Study Link Between Vaccines and Autism, AOC Says Musk is Unintelligent & SDNY

38.6K19