Premium Only Content

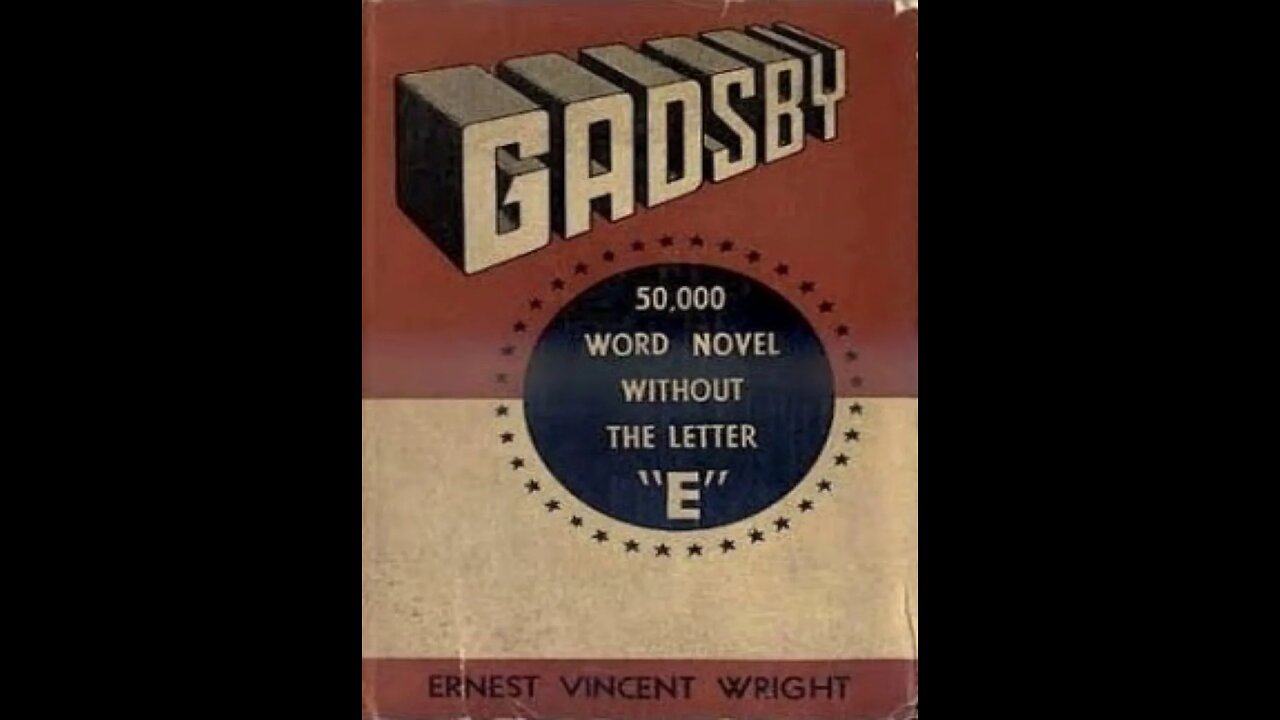

Gadsby, by Ernest Vincent Wright, 1939. A Puke AudioBook

Reformatted for Machine Text.

Not to be confused with "The Great Gatsby" By F. S. Fitzgerald.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Gadsby

This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online

at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States,

you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located

before using this eBook.

Title: Gadsby

a story of over 50,000 words without using the letter "E"

Author: Ernest Vincent Wright

Release date: November 13, 2014 [eBook #47342]

Language: English

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GADSBY ***

E-text prepared by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net)

GADSBY

+--------------------------------+

| _A Story of Over 50,000 Words_ |

| _Without Using the Letter "E"_ |

+--------------------------------+

by

ERNEST VINCENT WRIGHT

Wetzel Publishing Co., Inc.

: Los Angeles, California :

Copyright 1939

by

Wetzel Publishing Co., Inc.

TO YOUTH!

[Illustration: ERNEST VINCENT WRIGHT]

INTRODUCTION

The entire manuscript of this story was written with the E type-bar of

the typewriter _tied down_; thus making it impossible for that letter

to be printed. This was done so that none of that vowel might slip in,

accidentally; and many _did_ try to do so!

There is a great deal of information as to what _Youth_ can do, if

given a chance; and, though it starts out in somewhat of an impersonal

vein, there is plenty of thrill, rollicking comedy, love, courtship,

marriage, patriotism, sudden tragedy, _a determined stand against

liquor_, and some amusing political aspirations in a small growing town.

In writing such a story,--purposely avoiding all words containing

the vowel E, there are a great many difficulties. The greatest of

these is met in the past tense of verbs, almost all of which end

with "--ed." Therefore substitutes must be found; and they are _very

few_. This will cause, at times, a somewhat monotonous use of such

words as "said;" for neither "replied," "answered" nor "asked" can

be used. Another difficulty comes with the elimination of the common

couplet "of course," and its very common connective, "consequently;"

which will, unavoidably cause "bumpy spots." The numerals also cause

plenty of trouble, for none between six and thirty are available. When

introducing young ladies into the story, this is a _real_ barrier; for

what young woman wants to have it known that she is over thirty? And

this restriction on numbers, of course taboos all mention of dates.

Many abbreviations also must be avoided; the most common of all, "Mr."

and "Mrs." being particularly troublesome; for those words, if read

aloud, plainly indicate the E in their orthography.

As the vowel E is used more than five times oftener than any other

letter, this story was written, not through any attempt to attain

literary merit, but due to a somewhat balky nature, caused by hearing

it so constantly claimed that "it can't be done; for you _cannot_ say

anything at all without using E, and make smooth continuity, with

perfectly grammatical construction--" so 'twas said.

Many may think that I simply "drop" the E's, filling the gaps with

apostrophes. A perusal of the book will show that this is not so. All

words used are _complete_; are correctly spelled and properly used.

This has been accomplished through the use of synonyms; and, by so

twisting a sentence around as to avoid ambiguity. The book may prove a

valuable aid to school children in English composition.

People, as a rule, will not stop to realize what a task such an attempt

actually is. As I wrote along, in long-hand at first, a whole army

of little E's gathered around my desk, all eagerly expecting to be

called upon. But gradually as they saw me writing on and on, without

even noticing them, they grew uneasy; and, with excited whisperings

amongst themselves, began hopping up and riding on my pen, looking down

constantly for a chance to drop off into some word; for all the world

like sea-birds perched, watching for a passing fish! But when they saw

that I had covered 138 pages of typewriter size paper, they slid off

onto the floor, walking sadly away, arm in arm; but shouting back: "You

certainly must have a hodge-podge of a yarn there without _Us!_ Why,

man! We are in every story ever written, _hundreds of thousands of

times!_ This is the first time we ever were shut out!"

Pronouns also caused trouble; for such words as he, she, they, them,

theirs, her, herself, myself, himself, yourself, etc., could not be

utilized. But a particularly annoying obstacle comes when, almost

through a long paragraph you can find no words with which to continue

that line of thought; hence, as in Solitaire, you are "stuck," and must

go way back and start another; which, of course, must perfectly fit the

preceding context.

I have received some extremely odd criticisms since the Associated

Press widely announced that such a book was being written. A

rapid-talking New York newspaper columnist wanted to know how I would

get over the plain fact that my name contains the letter E three times.

As an author's name is _not_ a part of his story, that criticism

did not hold water. And I received one most scathing epistle from a

lady (woman!) denouncing me as a "genuine fake;" (that paradox being

a most interesting one!), and ending by saying:--"Everyone knows

that such a feat is impossible." All right. Then the impossible has

been accomplished; (a paradox to equal hers!) Other criticism may be

directed at the Introduction; but this section of a story _also_ is not

part of it. The author is entitled to it, in order properly to explain

his work. The story required five and a half months of concentrated

endeavor, with so many erasures and retrenchments that I tremble as

I think of them. Of course anybody can write such a story. All that

is needed is a piece of string tied from the E type-bar down to some

part of the base of the typewriter. Then simply go ahead and type your

story. Incidentally, you should have some sort of a bromide preparation

handy, for use when the going gets rough, as it most assuredly will!

Before the book was in print, I was freely and openly informed "there

is a trick, or catch," somewhere in that claim that there is not one

letter E in the entire book, after you leave the Introduction. Well; it

is the privilege of the reader to unearth any such deception that he

or she may think they can find. I have even ordered the printer not to

head each chapter with the words "Chapter 2," etc., on account of that

bothersome E in that word.

In closing let me say that I trust you may learn to love all the young

folks in the story, as deeply as I have, in introducing them to you.

Like many a book, it grows more and more interesting as the reader

becomes well acquainted with the characters.

Los Angeles, California

February, 1939

I

If Youth, throughout all history, had had a champion to stand up for

it; to show a doubting world that a child can think; and, possibly,

do it practically; you wouldn't constantly run across folks today

who claim that "a child don't know anything." A child's brain starts

functioning at birth; and has, amongst its many infant convolutions,

thousands of dormant atoms, into which God has put a mystic possibility

for noticing an adult's act, and figuring out its purport.

Up to about its primary school days a child thinks, naturally, only of

play. But many a form of play contains disciplinary factors. "You can't

do this," or "that puts you out," shows a child that it must think,

practically, or fail. Now, if, throughout childhood, a brain has no

opposition, it is plain that it will attain a position of "status quo,"

as with our ordinary animals. Man knows not why a cow, dog or lion was

not born with a brain on a par with ours; why such animals cannot add,

subtract, or obtain from books and schooling, that paramount position

which Man holds today.

But a human brain is not in that class. Constantly throbbing and

pulsating, it rapidly forms opinions; attaining an ability of its own;

a fact which is startlingly shown by an occasional child "prodigy"

in music or school work. And as, with our dumb animals, a child's

inability convincingly to impart its thoughts to us, should not class

it as ignorant.

Upon this basis I am going to show you how a bunch of bright young

folks did find a champion; a man with boys and girls of his own; a man

of so dominating and happy individuality that Youth is drawn to him

as is a fly to a sugar bowl. It is a story about a small town. It is

not a gossipy yarn; nor is it a dry, monotonous account, full of such

customary "fill-ins" as "romantic moonlight casting murky shadows down

a long, winding country road." Nor will it say anything about tinklings

lulling distant folds; robins carolling at twilight, nor any "warm glow

of lamplight" from a cabin window. No. It is an account of up-and-doing

activity; a vivid portrayal of Youth as it is today; and a practical

discarding of that worn-out notion that "a child don't know anything."

Now, any author, from history's dawn, always had that most important

aid to writing:--an ability to call upon any word in his dictionary in

building up his story. That is, our strict laws as to word construction

did not block his path. But in _my_ story that mighty obstruction

_will_ constantly stand in my path; for many an important, common word

I cannot adopt, owing to its orthography.

I shall act as a sort of historian for this small town; associating

with its inhabitants, and striving to acquaint you with its youths,

in such a way that you can look, knowingly, upon any child, rich

or poor; forward or "backward;" your own, or John Smith's, in your

community. You will find many young minds aspiring to know how, and WHY

such a thing is so. And, if a child shows curiosity in that way, how

ridiculous it is for you to snap out:--

"Oh! Don't ask about things too old for you!"

Such a jolt to a young child's mind, craving instruction, is apt so

to dull its avidity, as to hold it back in its school work. Try to

look upon a child as a small, soft young body and a rapidly growing,

constantly inquiring brain. It must grow to maturity slowly. Forcing a

child through school by constant night study during hours in which it

should run and play, can bring on insomnia; handicapping both brain and

body.

Now this small town in our story had grown in just that way:--slowly;

in fact, much _too_ slowly to stand on a par with many a thousand

of its kind in this big, vigorous nation of ours. It was simply

stagnating; just as a small mountain brook, coming to a hollow, might

stop, and sink from sight, through not having a will to find a way

through that obstruction; or around it. You will run across such a

dormant town, occasionally; possibly so dormant that only outright

isolation by a fast-moving world, will show it its folly. If you will

tour Asia, Yucatan, or parts of Africa and Italy, you will find many

sad ruins of past kingdoms. Go to Indo-China and visit its gigantic

Ankhor Vat; call at Damascus, Baghdad and Samarkand. What sorrowful

lack of ambition many such a community shows in thus discarding such

high-class construction! And I say, again, that so will Youth grow

dormant, and hold this big, throbbing world back, if no champion backs

it up; thus providing it with an opportunity to show its ability for

looking forward, and improving unsatisfactory conditions.

So this small town of Branton Hills was lazily snoozing amidst

up-and-doing towns, as Youth's Champion, John Gadsby, took hold of it;

and shook its dawdling, flabby body until its inhabitants thought a

tornado had struck it. Call it tornado, volcano, military onslaught,

or what you will, this town found that it had a bunch of kids who had

wills that would admit of no snoozing; for that is Youth, on its

forward march of inquiry, thought and action.

If you stop to think of it, you will find that it is customary for

our "grown-up" brain to cast off many of its functions of its youth;

and to think only of what it calls "topics of maturity." Amongst such

discards, is many a form of happy play; many a muscular activity such

as walking, running, climbing; thus totally missing that alluring "joy

of living" of childhood. If you wish a vacation from financial affairs,

just go out and play with Youth. Play "blind-man's buff," "hop-scotch,"

"ring toss," and football. Go out to a charming woodland spot on a

picnic with a bright, happy, vivacious group. Sit down at a corn roast;

a marshmallow toast; join in singing popular songs; drink a quart of

good, rich milk; burrow into that big lunch box; and all such things

as banks, stocks, and family bills, will vanish on fairy wings, into

oblivion.

But this is not a claim that Man should stay always youthful. Supposing

that that famous Spaniard, landing upon Florida's coral strands, had

found that mythical Fountain of Youth; what a calamity for mankind! A

world without maturity of thought; without man's full-grown muscular

ability to construct mighty buildings, railroads and ships; a world

without authors, doctors, savants, musicians; nothing but Youth! I can

think of but a solitary approval of such a condition; for such a horror

as war would not,--could not occur; for a child is, naturally, a small

bunch of sympathy. I know that boys will "scrap;" also that "spats"

will occur amongst girls; but, at such a monstrosity as killings by

bombing towns, sinking ships, or mass annihilation of marching troops,

childhood would stand aghast. Not a tiny bird would fall; nor would

any form of gun nor facility for manufacturing it, insult that almost

Holy purity of youthful thought. Anybody who knows that wracking sorrow

brought upon a child by a dying puppy or cat, knows that childhood can

show us that our fighting, our policy of "a tooth for a tooth," is

abominably wrong.

So, now to start our story:--

Branton Hills was a small town in a rich agricultural district; and

having many a possibility for growth. But, through a sort of smug

satisfaction with conditions of long ago, had no thought of improving

such important adjuncts as roads; putting up public buildings, nor

laying out parks; in fact a dormant, slowly dying community. So

satisfactory was its status that it had no form of transportation to

surrounding towns but by railroad, or "old Dobbin." Now, any town thus

isolating its inhabitants, will invariably find this big, busy world

passing it by; glancing at it, curiously, as at an odd animal at a

circus; and, you will find, caring not a whit about its condition.

Naturally, a town should grow. You can look upon it as a child; which,

through natural conditions, should attain manhood; and add to its

surrounding thriving districts its products of farm, shop, or factory.

It should show a spirit of association with surrounding towns; crawl

out of its lair, and find how backward it is.

Now, in all such towns, you will find, occasionally, an individual born

with that sort of brain which, knowing that his town is backward, longs

to start things toward improving it; not only its living conditions,

but adding an institution or two, such as any _city_, big or small,

maintains, gratis, for its inhabitants. But so forward looking a man

finds that trying to instill any such notions into a town's ruling body

is about as satisfactory as butting against a brick wall. Such "Boards"

as you find ruling many a small town, function from such a soporific

rut that any hint of digging cash from its cast iron strong box with

its big brass padlock, will fall upon minds as rigid as rock.

Branton Hills _had_ such a man, to whom such rigidity was as annoying

as a thorn in his foot. Continuous trials brought only continual

thorn-pricks; until, finally, a brilliant plan took form as John

Gadsby found Branton Hills' High School pupils waking up to Branton

Hills' sloth. Gadsby continually found this bright young bunch asking:--

"Aw! Why is this town so slow? It's nothing but a dry twig!!"

"Ha!" said Gadsby; "A dry twig! That's it! Many a living, blossoming

branch all around us, and this solitary dry twig, with a tag hanging

from it, on which you will find: 'Branton Hills; A twig too lazy to

grow!'"

Now this put a "hunch" in Gadsby's brain, causing him to say; "A High

School pupil is not a child, now. Naturally a High School boy has not

a man's qualifications; nor has a High School girl womanly maturity.

But such kids, born in this swiftly moving day, think out many a notion

which will work, but which would pass our dads and granddads in cold

disdain. Just as ships pass at night. But supposing that such ships

should show a light in passing; or blow a horn; or, if--if--if--By

Golly! I'll do it!"

And so Gadsby sat on his blossom-bound porch on a mild Spring morning,

thinking and smoking. Smoking can calm a man down; and his thoughts

had so long and so constantly clung to this plan of his that a cool

outlook as to its promulgation was not only important, but paramount.

So, as his cigar was whirling and puffing rings aloft; and as groups

of bright, happy boys and girls trod past, to school, his plan rapidly

took form as follows:--

"Youth! What is it? Simply a start. A start of what? Why, of that most

astounding of all human functions; thought. But man didn't start his

brain working. No. All that an adult can claim is a continuation, or

an amplification of thoughts, dormant in his youth. Although a child's

brain can absorb instruction with an ability far surpassing that of a

grown man; and, although such a young brain is bound by rigid limits,

it contains a capacity for constantly craving additional facts. So,

in our backward Branton Hills, I just _know_ that I can find boys and

girls who can show our old moss-back Town Hall big-wigs a thing or two.

Why! On Town Hall night, just go and sit in that room and find out just

how stupid and stubborn a Council, (put _into_ Town Hall, you know,

through popular ballot!), can act. Say that a road is badly worn. Shall

it stay so? Up jumps Old Bill Simpkins claiming that it is a townsman's

duty to fix up his wagon springs if that road is too rough for him!"

As Gadsby sat thinking thus, his plan was rapidly growing; and, in a

month, was actually starting to work. How? You'll know shortly; but

first, you should know this John Gadsby; a man of "around fifty;" a

family man, and known throughout Branton Hills for his high standard of

honor and altruism on any kind of an occasion for public good. A loyal

churchman, Gadsby was a man who, though admitting that an occasional

fault in our daily acts is bound to occur, had taught his two boys and

a pair of girls that, though folks do slip from what Scriptural authors

call that "straight and narrow path," it will not pay to risk your own

Soul by slipping, just so that you can laugh at your ability in staying

out of prison; for Gadsby, having grown up in Branton Hills, could

point to many such man or woman. So, with such firm convictions in his

mind, this upstanding man was constantly striving so to act that no

complaint from man, woman or child should bring a word of disapproval.

In his mind, what a man might do was that man's affair only and could

stain no Soul but his own. And his altruism taught that it is not

difficult to find many ways in which to bring joy to such as cannot,

through physical disability, go out to look for it; and that only a

small bit of joy, brought to a shut-in invalid will carry with it such

a warmth as can flow only from acts of human sympathy.

For many days Gadsby had thought of ways in which folks with a goodly

bank account could aid in building up this rapidly backsliding town of

Branton Hills. But, how to show that class what a contribution could

do? In this town, full of capitalists and philanthropists contributing,

off and on, for shipping warming pans to Zulus, Gadsby saw a solution.

In whom? Why, in just that bunch of bright, happy school kids, back

from many a visit to a _city_, and noting its ability in improving its

living conditions. So Gadsby thought of thus carrying an inkling to

such capitalists as to how this stagnating town could claim a big spot

upon our national map, which is now shown only in small, insignificant

print.

As a start, Branton Hills' "Daily Post" would carry a long story,

outlining a list of factors for improving conditions. This it did; but

it will always stay as a blot upon high minds and proud blood that not

a man or woman amongst such capitalists saw, in his plan, any call for

dormant funds. But did that stop Gadsby? Can you stop a rising wind?

Hardly! So Gadsby took into council about forty boys of his vicinity

and built up an Organization of Youth. Also about as many girls who had

known what it is, compulsorily to pass up many a picnic, or various

forms of sport, through a lack of public park land. So this strong,

vigorous combination of both youth and untiring activity, avidly took

up Gadsby's plan; for nothing so stirs up a youthful mind as an

opportunity for accomplishing anything that adults cannot do. And did

Gadsby _know_ Youth? I'll say so! His two sons and girls, now in High

or Grammar school, had taught him a thing or two; principal amongst

which was that all-dominating fact that, at a not too far distant day,

our young folks will occupy important vocational and also political

positions, and will look back upon this, _our_ day; smiling kindly at

our way of doing things. So, to say that many a Branton Hills "King of

Capital" got a bit huffy as a High School stripling was proving how

stubborn a rich man is if his dollars don't aid so vast an opportunity

for doing good, would put it mildly! Such downright _gall_ by a

half-grown kid to inform _him_; an outstanding light on Branton Hills'

tax list, that this town was sliding down hill; and would soon land

in an abyss of national oblivion! And our Organization girls! _How_

Branton Hills' rich old widows and plump matrons did sniff in disdain

as a group of High School pupils brought forth straightforward claims

that cash paving a road, is doing good practical work, but, in filling

up a strong box, is worth nothing to our town.

Oh, that class of nabobs! How thoroughly Gadsby _did_ know its

parsimony!! And how thoroughly did this hard-planning man know just

what a constant onslaught by Youth could do. So, in about a month, his

"Organization" had "waylaid," so to say, practically half of Branton

Hills' cash kings; and had so won out, through that commonly known

"pull" upon an adult by a child asking for what plainly is worthy,

that his mail brought not only cash, but two rich landlords put at his

disposal, tracts of land "for any form of occupancy which can, in any

way, aid our town." This land Gadsby's Organization promptly put into

growing farm products for gratis distribution to Branton Hills' poor;

and that burning craving of Youth for activity soon had it sprouting

corn, squash, potato, onion and asparagus crops; and, to "doll it up a

bit," put in a patch of blossoming plants.

Naturally any man is happy at a satisfactory culmination of his plans

and so, as Gadsby found that public philanthropy was but an affair

of plain, ordinary approach, it did not call for much brain work to

find that, possibly also, a way might turn up for putting handicraft

instruction in Branton Hills' schools; for schooling, according to

him, did not consist only of books and black-boards. Hands also should

know how to construct various practical things in woodwork, plumbing,

blacksmithing, masonry, and so forth; with thorough instruction

in sanitation, and that most important of all youthful activity,

gymnastics. For girls such a school could instruct in cooking, suit

making, hat making, fancy work, art and loom-work; in fact, about any

handicraft that a girl might wish to study, and which is not in our

standard school curriculum. But as Gadsby thought of such a school,

no way for backing it financially was in sight. Town funds naturally,

should carry it along; but town funds and Town Councils do not always

form what you might call synonymous words. So it was compulsory that

cash should actually "drop into his lap," via a continuation of

solicitations by his now grandly functioning Organization of Youth.

So, out again trod that bunch of bright, happy kids, putting forth

such plain, straightforward facts as to what Manual Training would

do for Branton Hills, that many saw it in that light. But you will

always find a group, or individual complaining that such things would

"automatically dawn" on boys and girls without any training. Old Bill

Simpkins was loud in his antagonism to what was a "crazy plan to dip

into our town funds just to allow boys to saw up good wood, and girls

to burn up good flour, trying to cook biscuits." Kids, according to

him, should go to work in Branton Hills' shopping district, and profit

by it.

"Bah! Why not start a class to show goldfish how to waltz! _I_ didn't

go to any such school; and what am I now? _A Councilman!_ I can't saw a

board straight, nor fry a potato chip; but I can show you folks how to

hang onto your town funds."

Old Bill was a notorious grouch; but our Organization occasionally

did find a totally varying mood. Old Lady Flanagan, with four boys in

school, and a husband many days too drunk to work, was loud in approval.

"Whoops! Thot's phwat I calls a grand thing! Worra, worra! I wish Old

Man Flanagan had had sich an opporchunity. But thot ignorant old clod

don't know nuthin' but boozin', tobacca shmokin' and ditch-diggin'. And

you know thot our Council ain't a-payin' for no ditch-scoopin' right

now. So _I'll_ shout for thot school! For my boys can find out how to

fix thot barn door our old cow laid down against."

Ha, ha! What a circus our Organization had with such varying moods and

outlooks! But, finally such a school was built; instructors brought in

from surrounding towns; and Gadsby was as happy as a cat with a ball of

yarn.

As Branton Hills found out what it can accomplish if it starts out with

vigor and a will to win, our Organization thought of laying out a big

park; furnishing an opportunity for small tots to romp and play on

grassy plots; a park for all sorts of sports, picnics, and so forth;

sand lots for babyhood; cozy arbors for girls who might wish to study,

or talk. (You might, possibly, find a girl who _can_ talk, you know!);

also shady nooks and winding paths for old folks who might find comfort

in such. Gadsby thought that a park is truly a most important adjunct

to any community; for, if a growing population has no out-door spot at

which its glooms, slumps and morbid thoughts can vanish upon wings of

sunlight, amidst bright colorings of shrubs and sky, it may sink into a

grouchy, fault-finding, squabbling group; and making such a showing for

surrounding towns as to hold back any gain in population or valuation.

Gadsby had a goodly plot of land in a grand location for a park and

sold it to Branton Hills for a dollar; that stingy Council to lay it

out according to his plans. And _how_ his Organization did applaud him

for this, his first "solo work!"

But schools and parks do not fulfill all of a town's calls. Many minds

of varying kinds will long for an opportunity for finding out things

not ordinarily taught in school. So Branton Hills' Public Library

was found too small. As it was now in a small back room in our High

School, it should occupy its own building; down town, and handy for

all; and with additional thousands of books and maps. Now, if you think

Gadsby and his youthful assistants stood aghast at such a gigantic

proposition, you just don't know Youth, as it is today. But to whom

could Youth look for so big an outlay as a library building would cost?

Books also cost; librarians and janitors draw pay. So, with light,

warmth, and all-round comforts, it was a task to stump a full-grown

politician; to say nothing of a plain, ordinary townsman and a bunch

of kids. So Gadsby thought of taking two bright boys and two smart

girls to Washington, to call upon a man in a high position, who had

got it through Branton Hills' popular ballot. Now, any politician is a

convincing orator. (That is, you know, all that politics consists of!);

and this big man, in contact with a visiting capitalist, looking for a

handout for his own district, got a donation of a thousand dollars. But

that wouldn't _start_ a public library; to say nothing of maintaining

it. So, back in Branton Hills, again, our Organization was out, as

usual, on its war-path.

Branton Hills' philanthropy was now showing signs of monotony; so our

Organization had to work its linguistic ability and captivating tricks

full blast, until that thousand dollars had so grown that a library was

built upon a vacant lot which had grown nothing but grass; and only a

poor quality of it, at that; and many a child and adult quickly found

ways of profitably passing odd hours.

Naturally Old Bill Simpkins was snooping around, sniffing and

snorting at any signs of making Branton Hills "look cityish," (a word

originating in Bill's vocabulary.)

"Huh!! _I_ didn't put in any foolish hours with books in my happy

childhood in this good old town! But I got along all right; and am now

having my say in its Town Hall doings. Books!! Pooh! Maps! BAH!! It's

silly to squat in a hot room squinting at a lot of print! If you want

to know about a thing, go to work in a shop or factory of that kind,

and find out about it first-hand."

"But, Bill," said Gadsby, "shops want a man who knows what to do

without having to stop to train him."

"Oh, that's all bosh! If a boss shows a man what a tool is for; and

if that man is any good, at all, why bring up this stuff you call

training? That man grabs a tool, works 'til noon; knocks off for an

hour; works 'til----"

At this point in Bill's blow-up an Italian Councilman was passing, and

put in his oar, with:--

"Ha, Bill! You thinka your man can worka all right, firsta day, huh?

You talka crazy so much as a fool! I laugha tinkin' of you startin' on

a patcha for my boota! You lasta just a half hour. Thisa library all

righta. This town too mucha what I call tight-wad!"

Oh, hum!! It's a tough job making old dogs do tricks. But our

Organization was now holding almost daily sittings, and soon a

bright girl thought of having band music in that now popular park.

And _what_ do you think that stingy Council did? It actually built a

most fantastic band-stand; got a contract with a first-class band,

and all without so much as a Councilman fainting away!! So, finally,

on a hot July Sunday, two solid hours of grand harmony brought joy

to many a poor Soul who had not for many a day, known that balm of

comfort which can "air out our brains' dusty corridors," and bring

such happy thrills, as Music, that charming Fairy, which knows no

human words, can bring. Around that gaudy band-stand, at two-thirty

on that first Sunday, sat or stood as happy a throng of old and young

as any man could wish for; and Gadsby and his "gang" got hand-clasps

and hand-claps, from all. A good band, you know, not only can stir and

thrill you; for it can play a soft crooning lullaby, a lilting waltz or

polka; or, with its wood winds, bring forth old songs of our childhood,

ballads of courting days, or hymns and carols of Christmas; and can

suit all sorts of folks, in all sorts of moods; for a Spaniard,

Dutchman or Russian can find similar joy with a man from Italy, Norway

or far away Brazil.

II

By now, Branton Hills was so proud of not only its "smarting up," but

also of its startling growth, on that account, that an application was

put forth for its incorporation as a city; a small city, naturally,

but full of that condition of Youth, known as "growing pains." So its

shabby old "Town Hall" sign was thrown away, and a black and gold onyx

slab, with "CITY HALL" blazing forth in vivid colors, put up, amidst

band music, flag waving, parading and oratory. In only a month from

that glorious day, Gadsby found folks "primping up"; girls putting on

bright ribbons; boys finding that suits could stand a good ironing;

and rich widows and portly matrons almost out-doing any rainbow in

brilliancy. An occasional shop along Broadway, which had a rattly door

or shaky windows was put into first class condition, to fit Branton

Hills' status as a city. Old Bill Simpkins was strutting around, as

pompous as a drum-major; for, now, that old Town Council would function

as a CITY council; HIS council! His own stamping ground! According to

him, from it, at no far day, "Bill Simpkins, City Councilman," would

show an anxiously waiting world how to run a city; though probably, I

think, how _not_ to run it.

It is truly surprising what a narrow mind, what a blind outlook a man,

brought up with practically no opposition to his boyhood wants, can

attain; though brought into contact with indisputably important data

for improving his city. Our Organization boys thought Bill "a bit off;"

but Gadsby would only laugh at his blasts against paying out city

funds; for, you know, all bombs don't burst; you occasionally find a

"dud."

But this furor for fixing up rattly doors or shaky windows didn't last;

for Old Bill's oratory found favor with a bunch of his old tight-wads,

who actually thought of inaugurating a campaign against Gadsby's

Organization of Youth. As soon as this was known about town, that

mythical pot, known as Public Opinion, was boiling furiously. A vast

majority stood back of Gadsby and his kids; so, old Bill's ranks could

count only on a small group of rich old Shylocks to whom a bank-book

was a thing to look into or talk about only annually; that is, on

bank-balancing days. This small minority got up a slogan:--"Why Spoil

a Good Old Town?" and actually did, off and on, talk a shopman out of

fixing up his shop or grounds. This, you know, put additional vigor

into our Organization; inspiring a boy to bring up a plan for calling

a month,--say July,--"pick-up, paint-up and wash-up month;" for it was

a plain fact that, all about town, was many a shabby spot; a lot of

buildings could stand a good coat of paint, and yards raking up; thus

showing surrounding towns that not only _could_ Branton Hills "doll

up," but had a class of inhabitants who gladly would go at such a plan,

and carry it through. So Gadsby got his "gang" out, to sally forth and

any man or woman who did not jump, at first, at such a plan by vigorous

Youth, was always brought around, through noticing how poorly a shabby

yard did look. So Gadsby put in Branton Hills' "Post" this stirring

call:--

"Raking up your yard or painting your building is simply improving it

both in worth; artistically and from a utilization standpoint. I know

that many a city front lawn is small; but, if it is only fairly big,

a walk, cut curvingly, will add to it, surprisingly. That part of a

walk which runs to your front door could show rows of small rocks rough

and natural; and grading from small to big; but _no_ 'hit-or-miss'

layout. You can so fix up your yard as to form an approach to unity in

plan with such as adjoin you; though without actual duplication; thus

providing harmony for all who may pass by. It is, in fact, but a bit

of City Planning; and anybody who aids in such work is a most worthy

inhabitant. So, _cut_ your scraggly lawns! _Trim_ your old, shaggy

shrubs! Bring into artistic form, your grass-grown walks!"

(Now, naturally, in writing such a story as this, with its conditions

as laid down in its Introduction, it is not surprising that an

occasional "rough spot" in composition is found. So I trust that a

critical public will hold constantly in mind that I am voluntarily

avoiding words containing that symbol which is, _by far_, of most

common inclusion in writing our Anglo-Saxon as it is, today. Many of

our most common words cannot show; so I must adopt synonyms; and so

twist a thought around as to say what I wish with as much clarity as I

can.)

So, now to go on with this odd contraption:

By Autumn, a man who took his vacation in July, would hardly know his

town upon coming back, so thoroughly had thousands "dug in" to aid in

its transformation.

"Boys," said Gadsby, "you can pat your own backs, if you can't find

anybody to do it for you. This city is proud of you. And, girls, just

sing with joy; for not only is your city proud of you, but I am, too."

"But how about you, sir, and your work?"

This was from Frank; a boy brought up to think fairly on all things.

"Oh," said Gadsby laughingly, "I didn't do much of anything but boss

you young folks around. If our Council awards any diplomas, I don't

want any. I would look ridiculous strutting around with a diploma with

a pink ribbon on it, now wouldn't I!"

This talk of diplomas was as a bolt from a bright sky to this young,

hustling bunch. But, though Gadsby's words did sound as though a grown

man wouldn't want such a thing, that wasn't saying that a young boy or

girl wouldn't; and with this surprising possibility ranking in young

minds, many a kid was in an anti-soporific condition for parts of many

a night.

But a kindly Councilman actually did bring up a bill about this diploma

affair, and his collaborators put it through; which naturally brought

up talk as how to award such diplomas. At last it was thought that a

big public affair at City Hall, with our Organization on a platform,

with Branton Hills' Mayor and Council, would furnish an all-round,

satisfactory way.

Such an occasion was worthy of a lot of planning; and a first thought

was for flags and bunting on all public buildings; with a grand

illumination at night. Stationary lights should glow from all points

on which a light could stand, hang, or swing; and gigantic rays should

swoop and swish across clouds and sky. Bands should play; boys and

girls march and sing; and a vast crowd would pour into City Hall. As on

similar occasions, a bad rush for chairs was apt to occur, a company

of military units should occupy all important points, to hold back

anything simulating a jam.

Now, if you think our Organization wasn't all agog and wild, with

youthful anticipation at having a diploma for work out of school

hours, you just don't know Youth. Boys and girls, though not full

grown inhabitants of a city, do know what will add to its popularity;

and having had a part in bringing about such conditions, it was but

natural to look back upon such, as any military man might at winning a

difficult fight.

So, finally our big day was at hand! That it might not cut into school

hours, it was on a Saturday; and, by noon, about a thousand kids,

singing, shouting and waving flags, stood in formation at City Park,

awaiting, with growing thrills, a signal which would start as big a

turn-out as Branton Hills had known in all its history. Up at City

Hall awaiting arrivals of city officials, a big crowd sat; row upon

row of chairs which not only took up all floor room, but also many a

small spot, in door-way or on a balcony in which a chair or stool could

find footing; and all who could not find such an opportunity willingly

stood in back. Just as a group of officials sat down on that flag-bound

platform, distant throbbing of drums, and bright, snappy band music

told of Branton Hills' approaching thousands of kids, who, finally

marching in through City Hall's main door, stood in a solid mass around

that big room.

Naturally Gadsby had to put his satisfaction into words; and, advancing

to a mahogany stand, stood waiting for a storm of hand-clapping and

shouts to quit, and said:--

"Your Honor, Mayor of Branton Hills, its Council, and all you out in

front:--If you would only stop rating a child's ability by your own;

and try to find out just _what_ ability a child has, our young folks

throughout this big world would show a surprisingly willing disposition

to try things which would bring your approbation. A child's brain is an

astonishing thing. It has, in its construction, an astounding capacity

for absorbing what is brought to it; and not only to think about, but

to find ways for improving it. It is today's child who, tomorrow,

will, you know, laugh at our ways of doing things. So, in putting

across this campaign of building up our community into a municipality

which has won acclaim, not only from its officials and inhabitants,

but from surrounding towns I found, in our young folks, an out-and-out

inclination to assist; and you, today, can look upon it as labor in

which your adult aid was but a small factor. So now, my Organization of

Youth, if you will pass across this platform, your Mayor will hand you

your diplomas."

Not in all Branton Hills' history had any boy or girl known such a

thrill as upon winning that hard-won roll! And from solid banks of

humanity roars of congratulation burst forth. As soon as Mayor Brown

shook hands (and such tiny, warm, soft young hands, too!) with all, a

big out-door lunch was found waiting on a charming lawn back of City

Hall; and this was no World War mobilization lunch of doughnuts and a

hot dog sandwich; but, as two of Gadsby's sons said, was "an all-round,

good, big fill-up;" and many a boy's and girl's "tummy" was soon as

round and taut as a balloon.

As twilight was turning to dusk, boys in an adjoining lot shot skyward

a crashing bomb, announcing a grand illumination as a fitting climax

for so glorious a day; and thousands sat on rock-walls, grassy knolls,

in cars or at windows, with a big crowd standing along curbs and

crosswalks. Myriads of lights of all colors, in solid balls, sprays,

sparkling fountains, and bursts of glory, shot, in criss-cross paths,

up and down, back and forth, across a star-lit sky; providing a display

without a par in local annals.

But not only did Youth thrill at so fantastic a show. Adults had many a

Fourth of July brought back from a distant past; in which our national

custom wound up our most important holiday with a similar display;

only, in our Fourths of long ago, horrifying, gigantic concussions

would disturb old folks and invalids until midnight; at which hour,

according to law, all such carrying-on must stop. But did it? Possibly

in _your_ town, but not around _my_ district! All Fourth of July

outfits don't always function at first, you know; and no kid, (or

adult!) would think of quitting until that last pop should pop; or that

last bang should bang. And so, many a dawn on July fifth found things

still going, full blast.

III

Youth cannot stay for long in a condition of inactivity; and so, for

only about a month did things so stand, until a particularly bright

girl in our Organization, thought out a plan for caring for infants of

folks who had to go out, to work; and this bright kid soon had a group

of girls who would join, during vacation, in voluntarily giving up four

days a month to such work. With about fifty girls collaborating, all

districts had this most gracious aid; and a girl would not only watch

and guard, but would also instruct, as far as practical, any such tot

as had not had its first schooling. Such work by young girls still

in school was a grand thing; and Gadsby not only stood up for such

loyalty, but got at his boys to find a similar plan; and soon had a

full troop of Boy Scouts; uniforms and all. This automatically brought

about a Girl Scout unit; and, through a collaboration of both, a form

of club sprang up. It was a club in which any boy or girl of a family

owning a car would call mornings for pupils having no cars, during

school days, for a trip to school and back. This was not only a saving

in long walks for many, but also took from a young back, that hard,

tiring strain from lugging such armfuls of books as you find pupils

laboriously carrying, today. Upon arriving at a school building, many

cars would unload so many books that Gadsby said:--

"You would think that a Public Library branch was moving in!" This car

work soon brought up a thought of giving similar aid to ailing adults;

who, not owning a car, could not know of that vast display of hill and

plain so common to a majority of our townsfolks. So a plan was laid, by

which a car would call two days a month; and for an hour or so, follow

roads winding out of town and through woods, farm lands and suburbs;

showing distant ponds, and that grand arch of sky which "shut-ins"

know only from photographs. Ah; _how_ that plan did stir up joyous

anticipation amongst such as thus had an opportunity to call upon old,

loving pals, and talk of old customs and past days! Occasionally such a

talk would last so long that a youthful motorist, waiting dutifully at

a curb, thought that a full family history of both host and visitor was

up for an airing. But old folks always _will_ talk and it will not do a

boy or girl any harm to wait; for, you know, that boy or girl will act

in just that way, at a not too far-off day!

But, popular as this touring plan was, it had to stop; for school

again took all young folks from such out-door activity. Nobody was so

sorry at this as Gadsby, for though Branton Hills' suburban country is

glorious from March to August, it is also strong in its attractions

throughout Autumn, with its artistic colorings of fruits, pumpkins,

corn-shocks, hay-stacks and Fall blossoms. So Gadsby got a big

motor-coach company to run a bus a day, carrying, gratis, all poor or

sickly folks who had a doctor's affidavit that such an outing would aid

in curing ills arising from too constant in-door living; and so, up

almost to Thanksgiving, this big coach ran daily.

As Spring got around again, this "man-of-all-work" thought of driving

away a shut-in invalid's monotony by having musicians go to such rooms,

to play; or, by taking along a vocalist or trio, sing such old songs

as always bring back happy days. This work Gadsby thought of paying

for by putting on a circus. And _was_ it a circus? _It was!!_ It had

boys forming both front and hind limbs of animals totally unknown to

zoology; girls strutting around as gigantic birds of also doubtful

origin; an array of small living animals such as trick dogs and goats,

a dancing pony, a group of imitation Indians, cowboys, cowgirls, a

kicking trick jack-ass; and, talk about clowns! Forty boys got into

baggy pantaloons and fools' caps; and no circus, including that first

of all shows in Noah's Ark, had so much going on. Gymnasts from our

school gymnasium, tumbling, jumping and racing; comic dancing; a clown

band; high-swinging artists, and a funny cop who didn't wait to find

out who a man was, but hit him anyway. And, as no circus _is_ a circus

without boys shouting wildly about pop-corn and cold drinks, Gadsby saw

to it that such boys got in as many patrons' way as any ambitious youth

could; and that is "going strong," if you know boys, at all!

But what about profits? It not only paid for all acts which his

Organization couldn't put on, but it was found that a big fund for many

a day's musical visitations, was on hand.

And, now a word or two about municipal affairs in this city; or _any_

city, in which nobody will think of doing anything about its poor

and sick, without a vigorous prodding up. City Councils, now-a-days,

willingly grant big appropriations for paving, lights, schools, jails,

courts, and so on; but invariably fight shy of charity; which is

nothing but sympathy for anybody who is "down and out." No man can

say that Charity will not, during coming days, aid _him_ in supporting

his family; and it was Gadsby's claim that _humans_:--_not blocks of

buildings_, form what Mankind calls a city. But what would big, costly

buildings amount to, if all who work in such cannot maintain that good

physical condition paramount in carrying on a city's various forms of

labor? And not only _physical_ good, but also a mind happy from lack of

worry and of that stagnation which always follows a monotonous daily

grind. So our Organization was soon out again, agitating City Officials

and civilians toward building a big Auditorium in which all kinds of

shows and sports could occur, with also a swimming pool and hot and

cold baths. Such a building cannot so much as start without financial

backing; but gradually many an iron-bound bank account was drawn upon

(much as you pull a tooth!), to buy bonds. Also, such a building won't

grow up in a night; nor was a spot upon which to put it found without

a lot of agitation; many wanting it in a down-town district; and also,

many who had vacant land put forth all sorts of claims to obtain cash

for lots upon which a big tax was paid annually, without profits. But

all such things automatically turn out satisfactorily to a majority;

though an ugly, grasping landlord who lost out, would viciously squawk

that "municipal graft" was against him.

Now Gadsby was vigorously against graft; not only in city affairs but

in any kind of transaction; and that stab brought forth such a flow of

oratory from him, that as voting for Mayor was soon to occur, it, and a

long list of good works, soon had him up for that position. But Gadsby

didn't want such a nomination; still, thousands of townsfolks who had

known him from childhood, would not hark to anything but his candidacy;

and, soon, on window cards, signs, and flags across Broadway, was

his photograph and "GADSBY FOR MAYOR;" and a campaign was on which

still rings in Branton Hills' history as "hot stuff!" Four aspiring

politicians ran in opposition; and, as all had good backing, and Gadsby

only his public works to fall back on, things soon got looking gloomy

for him. His antagonists, standing upon soap box, auto truck, or

hastily built platforms, put forth, with prodigious vim, claims that

"our fair city will go back to its original oblivion if _I_ am not its

Mayor!" But our Organization now took a hand, most of which, now out of

High School, was growing up rapidly; and anybody who knows anything at

all about Branton Hills' history, knows that, if this band of bright,

loyal pals of Gadsby's was out to attain a goal, it was mighty apt to

start things humming. To say that Gadsby's rivals got a bad jolt as

it got around town that his "bunch of warriors" was aiding him, would

put it but mildly. _Two quit instantly_, saying that this is a day of

Youth and no adult has half a show against it! But two still hung on;

clinging to a sort of fond fantasy that Gadsby, not naturally a public

sort of man, might voluntarily drop out. But, had Gadsby so much as

thought of such an action, his Organization would quickly laugh it to

scorn.

"Why, good gracious!" said Frank Morgan, "if _anybody_ should sit in

that Mayor's chair in City Hall, it's you! Just look at what you did to

boost Branton Hills! Until you got it a-going it had but two thousand

inhabitants; now it has sixty thousand! And just ask your rivals to

point to any part of it that you didn't build up. Look at our Public

Library, municipal band, occupational class rooms; auto and bus trips;

and your circus which paid for music for sick folks. With you as Mayor,

_boy!_ What an opportunity to boss and swing things your own way! Why,

anything you might say is as good as law; and----"

"Now, hold on, boy!" said Gadsby, "a Mayor can't boss things in any

such a way as you think. A Mayor has a Council, which has to pass on

all bills brought up; and, my boy, upon arriving at manhood, you'll

find that a Mayor who _can_ boss a Council around, is a most uncommon

bird. And as for a Mayor's word amounting to a law, it's a mighty good

thing that it can't! Why, a Mayor can't do much of anything, today,

Frank, without a bunch of crazy bat-brains stirring up a rumpus about

his acts looking 'suspiciously shady.' Now that is a bad condition in

which to find a city, Frank. You boys don't know anything about graft;

but as you grow up you will find many flaws in a city's laws; but also

many points thoroughly good and fair. Just try to think what a city

would amount to if a solitary man could control its law making, as a

King or Sultan of old. That was why so many millions of inhabitants

would start wars and riots against a tyrant; for many a King _was_ a

tyrant, Frank, and had no thought as to how his laws would suit his

thousands of rich and poor. A law that might suit a rich man, might

work all kinds of havoc with a poor family."

"But," said Frank, "why should a King pass a law that would dissatisfy

anybody?"

Gadsby's parry to this rising youthful ambition for light on political

affairs was:--

"Why will a duck go into a pond?" and Frank found that though a growing

young man might know a thing or two, making laws for a city was a man's

job.

So, with a Mayoralty campaign on his hands, plus planning for that big

auditorium, Gadsby was as busy as a fly around a syrup jug; for a mass

of campaign mail had to go out; topics for orations thought up; and

contacts with his now truly important Organization of Youth, took so

many hours out of his days that his family hardly saw him, at all. Noon

naturally stood out as a good opportunity for oratory, as thousands,

out for lunch, would stop, in passing. But, also, many a hall rang with

plaudits as an antagonist won a point; but many a throng saw Gadsby's

good points, and plainly told him so by turning out voluminously at any

point at which his oratory was to flow. It was truly miraculous how

this man of shy disposition, found words in putting forth his plans for

improving Branton Hills, town of his birth. Many an orator has grown

up from an unassuming individual who had things worth saying; and who,

through that curious facility which is born of a conviction that his

plans had a practical basis, won many a ballot against such prolific

flows of high-sounding words as his antagonists had in stock. Many a

night Gadsby was "all in," as his worn-out body and an aching throat

sought his downy couch. No campaign is a cinch.

With so many minds amongst a city's population, just that many calls

for this or that swung back and forth until that most important of all

days,--voting day, was at hand. What crowds, mobs and jams did assail

all polling booths, casting ballots to land a party-man in City Hall!

If a voting booth was in a school building, as is a common custom

pupils had that day off; and, as Gadsby was Youth's champion, groups of

kids hung around, watching and hoping with that avidity so common with

youth, that Gadsby would win by a majority unknown in Branton Hills.

And Gadsby did!

As soon as it was shown by official count, Branton Hills was a riot,

from City Hall to City limits; throngs tramping around, tossing hats

aloft; for a hard-working man had won what many thousands thought was

fair and just.

IV

As soon as Gadsby's inauguration had put him in a position to do things

with authority, his first act was to start things moving on that big

auditorium plan, for which many capitalists had bought bonds. Again

public opinion had a lot to say as to how such a building should look,

what it should contain; how long, how high, how costly; with a long

string of ifs and buts.

Family upon family put forth claims for rooms for public forums in

which various thoughts upon world affairs could find opportunity for

discussion; Salvation Army officials thought that a big hall for a

public Sunday School class would do a lot of good; and that, lastly,

what I must, from this odd yarn's strict orthography, call a "film

show," should, without doubt occupy a part of such a building. Anyway,

talk or no talk, Gadsby said that it should stand as a building for

man, woman and child; rich or poor; and, barring its "film show,"

without cost to anybody. Branton Hills' folks could thus swim, do

gymnastics, talk on public affairs, or "just sit and gossip", at will.

So it was finally built in a charming park amidst shrubs and blossoms;

an additional honor for Gadsby.

But such buildings as Branton Hills now had could not fulfill all

functions of so rapidly growing a city; for you find, occasionally, a

class of folks who cannot afford a doctor, if ill. This was brought up

by a girl of our Organization, Doris Johnson, who, on Christmas Day, in

taking gifts to a poor family, had found a woman critically ill, and

with no funds for aid or comforts; and instantly, in Doris' quick young

mind a vision of a big city hospital took form; and, on a following day

Gadsby had his Organization at City Hall, to "just talk," (and you know

how that bunch _can_ talk!) to a Councilman or two.

Now, if any kind of a building in all this big world costs good, hard

cash to build, and furnish, it is a hospital; and it is also a building

which a public knows nothing about. So Mayor Gadsby saw that if his

Council would pass an appropriation for it, no such squabbling as had

struck his Municipal Auditorium plan, would occur. But Gadsby forgot

Branton Hills' landlords, all of whom had "a most glorious spot," just

right for a hospital; until, finally, a group of physicians was told to

look around. And did Branton Hills' landlords call upon Branton Hills'

physicians? I'll say so!! Anybody visiting town, not knowing what was

going on, would think that vacant land was as common as raindrops in a

cloudburst. Small plots sprang into public light which couldn't hold a

poultry barn, to say nothing of a big City Hospital. But no grasping

landlord can fool physicians in talking up a hospital location, so it

was finally built, on high land, with a charming vista across Branton

Hills' suburbs and distant hills; amongst which Gadsby's charity auto

and bus trips took so many happy invalids on past hot days.

Now it is only fair that our boys and girls of this famous Organization

of Youth, should walk forward for an introduction to you. So I will

bring forth such bright and loyal girls as Doris Johnson, Dorothy

Fitts, Lucy Donaldson, Marian Hopkins, Priscilla Standish, Abigail

Worthington, Sarah Young, and Virginia Adams. Amongst the boys, cast

a fond look upon Arthur Rankin, Frank Morgan, John Hamilton, Paul

Johnson, Oscar Knott and William Snow; as smart a bunch of Youth as you

could find in a month of Sundays.

As soon as our big hospital was built and functioning, Sarah Young

and Priscilla Standish, in talking with groups of girls, had found

a longing for a night-school, as so many folks had to work all day,

so couldn't go to our Manual Training School. So Mayor Gadsby took

it up with Branton Hills' School Board. Now school boards do not

always think in harmony with Mayors and Councils; in fact, what with

school boards, Councils, taxation boards, paving contractors, Sunday

closing-hour agitations, railway rights of way, and all-round political

"mud-slinging," a Mayor has a tough job.

Two of Gadsby's School Board said "NO!!" A right out-loud, slam-bang

big "NO!!" Two thought that a night school was a good thing; but four,

with a faint glow of financial wisdom, (a rarity in politics, today!)

saw no cash in sight for such an institution.

But Gadsby's famous Organization won again! Branton Hills did not

contain a family in which this Organization wasn't known; and many a

sock was brought out from hiding, and many a sofa pillow cut into, to

aid _any_ plan in which this group had a part.

But, just as funds had grown to what Mayor Gadsby thought would fill

all such wants, a row in Council as to this fund's application got so

hot that "His Honor" got mad; _mighty mad!!_ And said:--

"Why is it that any bill for appropriations coming up in this Council

has to kick up such a rumpus? Why can't you look at such things with a

public mind; for nothing can so aid toward passing bills as harmony.

This city is not holding off an attacking army. Branton Hills is not

a pack of wild animals, snapping and snarling by day; jumping, at a

crackling twig, at night. It is a city of _humans_; animals, if you

wish, but with a gift from On High of a _brain_, so far apart from all

dumb animals as to allow us to talk about our public affairs calmly and

thoughtfully. All this Night School rumpus is foolish. Naturally, what

is taught in such a school is an important factor; so I want to find

out from our Organization----"

At this point, old Bill Simpkins got up, with:

"This Organization of Youth stuff puts a kink in my spinal column!

Almost all of it is through school. So how can you bring such a group

forward as 'pupils?'"

"A child," said Gadsby, "who had such schooling as Branton Hills

affords is, naturally, still a pupil; for many will follow up a study

if an opportunity is at hand. Many adults also carry out a custom

of brushing up on unfamiliar topics; thus, also, ranking as pupils.

Possibly, Bill, if you would look up that word 'pupil,' you wouldn't

find so much fault with insignificant data."

"All right!" was Simpkins' snap-back; "but what I want to know is,

what our big Public Library is for. Your 'pupils' can find all sorts

of information in that big building. So why build a night school? It's

nothing but a duplication!"

"A library," said Gadsby, "is not a school. It has no instructors; you

cannot talk in its rooms. You may find a book or two on your study, or

you may not. You would find it a big handicap if you think that you can

accomplish much with no aid but that of a Public Library. Young folks

know what young folks want to study. It is foolish, say, to install a

class in Astronomy, for although it _is_ a 'Night School,' its pupils'

thoughts might not turn toward Mars, Saturn or shooting stars; but

shorthand, including training for typists amongst adults who, naturally

don't go to day schools, is most important, today; also History and

Corporation Law; and I know that a study of Music would attract many.

Any man or woman who works all day, but still wants to study at night,

should find an opportunity for doing so."

This put a stop to Councilman Simpkins' criticisms, and approval was

put upon Gadsby's plan; and it was but shortly that this school's

popularity was shown in a most amusing way. Branton Hills folks, in

passing it on going out for a show or social call, caught most savory

whiffs, as i

-

8:52

8:52

PukeOnABook

13 days agoRahan. Episode 123. By Roger Lecureux. The Valley of Flowers. A Puke (TM) Comic.

78 -

1:14:07

1:14:07

Glenn Greenwald

9 hours agoComedian Dave Smith On Trump's Picks, Israel, Ukraine, and More | SYSTEM UPDATE #370

147K150 -

1:09:07

1:09:07

Donald Trump Jr.

12 hours agoBreaking News on Latest Cabinet Picks, Plus Behind the Scenes at SpaceX & Darren Beattie Joins | TRIGGERED Ep.193

187K542 -

1:42:43

1:42:43

Roseanne Barr

7 hours ago $56.34 earnedGod Won, F*ck You | The Roseanne Barr Podcast #75

78.1K165 -

2:08:38

2:08:38

Slightly Offensive

9 hours ago $23.18 earnedDEEP STATE WINS?! Matt Gaetz OUSTED as AG & Russia ESCALATES War | Guest: The Lectern Guy

59.5K22 -

1:47:36

1:47:36

Precision Rifle Network

8 hours agoS3E8 Guns & Grub - the craziness continues

50K3 -

41:37

41:37

Kimberly Guilfoyle

10 hours agoPresident Trump Making all the Right Moves,Live with Border Union Chief Paul Perez & Lawyer Steve Baric | Ep. 176

141K39 -

19:38

19:38

Neil McCoy-Ward

13 hours agoMASS LAYOFFS Have Started... (How To Protect Your Income)

46.6K7 -

46:21

46:21

PMG

1 day ago $5.31 earned"Venezuelan Gang in 16 States, Animal Testing Crackdown, & Trump’s Nominee Battle"

33K10 -

LIVE

LIVE

VOPUSARADIO

12 hours agoPOLITI-SHOCK! WW3!?, BREAKDOWN OF THE WORLD EVENTS & R.A.G.E. (What it means & What's next!)

596 watching