Premium Only Content

A CIA War in Angola: Overthrowing Governments, Disinformation, Propaganda

More CIA stories from John Stockwell: https://thememoryhole.substack.com/

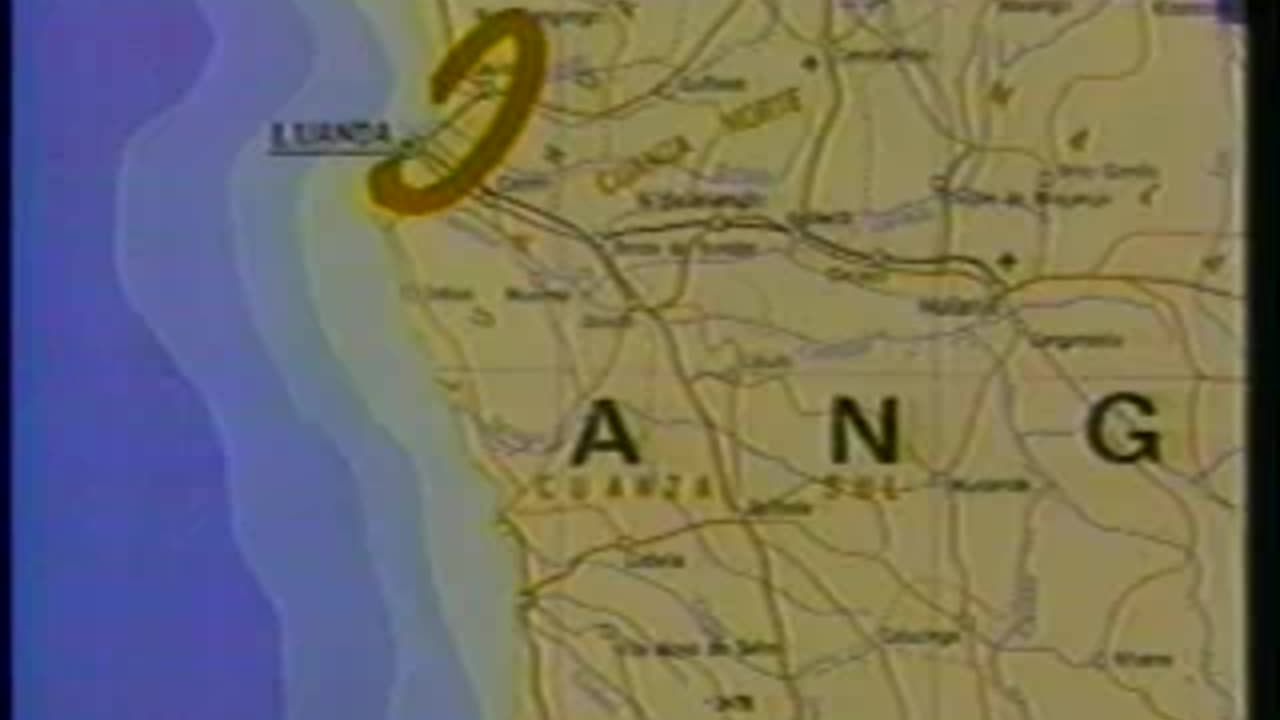

"Accent on Angola" offers a comprehensive exploration of the complex socio-political landscape in Angola during the late 1980s. Kenneth Jones, an authoritative figure on Cuba and a member of the Venceremos Brigade, shares firsthand insights garnered from recent visits to both Cuba and Angola. Jones delves into the historical context and the ongoing struggles faced by the Angolan government against U.S.-backed rebel forces and the South African military, extensively analyzing the dynamic geopolitical tensions at play.

This documentary amalgamates Jones's astute commentary with excerpts from Cuban television, showcasing three one-hour documentaries that spotlight the Cuban armed forces' pivotal role in defending the Angolan government. Additionally, the program integrates segments from previous interviews featuring John Stockwell, who previously led the CIA's Angolan program during the early 1970s. Stockwell's perspective offers a unique lens through which to view the historical evolution of the situation.

Recorded in December 1988, this documentary provides a multifaceted examination of the intricacies surrounding Angola's geopolitical landscape, shedding light on the historical complexities and contemporary challenges faced by the nation amidst external pressures and internal conflict.

As background to the reports of Cuban action, "[Fidel] Castro decided to send troops to Angola on November 4, 1975, in response to the South African invasion of that country, rather than vice versa as the Ford administration persistently claimed. The United States knew about South Africa's covert invasion plans, and collaborated militarily with its troops, contrary to what Secretary of State Henry Kissinger testified before Congress and wrote in his memoirs. Cuba made the decision to send troops without informing the Soviet Union and deployed them, contrary to what has been widely alleged, without any Soviet assistance for the first two months.[1]

"In a meeting including President Ford, Secretary of State Kissinger, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger, and CIA Director William Colby among others, U.S. intervention in Angola's civil war is discussed. In response to evidence of Soviet aid to the MPLA, Secretary Schlesinger says, "we might wish to encourage the disintegration of Angola.” Kissinger describes two meetings of the 40 Committee oversight group for clandestine operations in which covert operations were authorized: “The first meeting involved only money, but the second included some arms package."[2] Beginning in 1975, the CIA participated in the Angolan Civil War, hiring and training American, British, French and Portuguese private military contractors, as well as training National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) rebels under Jonas Savimbi, to fight against the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) led by Agostinho Neto.[citation needed]

John Stockwell commanded the CIA's Angola effort in 1975 to 1976.[3]

In a meeting including President Richard Nixon and Chinese Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping, Teng referred to an early conversation between Nixon and Mao Zedong regarding Angola. "We hope that through the work of both sides we can achieve a better situation there. The relatively complex problem is the involvement of South Africa. And I believe you are aware of the feelings of the black Africans toward South Africa." No CIA personnel were present, but this is mentioned in the context of setting US policy toward Angola, where CIA did have covert operations.

United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger replied, "We are prepared to push South Africa as soon as an alternative military force can be created." Nixon added "We hope your Ambassador in Zaire can keep us fully informed. It would be helpful."

Deng said "We have a good relationship with Zaire but what we can help them with is only some light weapons." To this, Kissinger replied, "We can give them weapons, but what they really need is training in guerrilla warfare. If you can give them light weapons it would help, but the major thing is training. Our specialty is not in guerrilla warfare (laughter in transcript)?" Deng mentioned that at various times, China had trained all the factions in Angola.[4]

1980s

Savimbi was strongly supported by the conservative Heritage Foundation. Heritage foreign policy analyst Michael Johns and other conservatives visited regularly with Savimbi in his clandestine camps in Jamba and provided the rebel leader with ongoing political and military guidance in his war against the Angolan government. During a visit to Washington, D.C. in 1986, Reagan invited Savimbi to meet with him at the White House. Following the meeting, Reagan spoke of UNITA winning "a victory that electrifies the world." Savimbi also met with Reagan's successor, George H. W. Bush, who promised Savimbi "all appropriate and effective assistance."[5]

The killing of Savimbi in February 2002 by the Angolan military led to the decline of UNITA's influence. Savimbi was succeeded by Paulo Lukamba Gato. Six weeks after Savimbi's death, UNITA agreed to a ceasefire with the MPLA, but even today Angola remains deeply divided politically between MPLA and UNITA supporters. Parliamentary elections in September 2008 resulted in an overwhelming majority for the MPLA, but their legitimacy was questioned by international observers.

In popular culture

The video game Call of Duty: Black Ops II uses CIA activities in Angola as part of the game context and setting.

The Angolan Civil War (Portuguese: Guerra Civil Angolana) was a civil war in Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war began immediately after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. It was a power struggle between two former anti-colonial guerrilla movements, the communist People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the anti-communist National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA).

The MPLA and UNITA had different roots in Angolan society and mutually incompatible leaderships, despite their shared aim of ending colonial rule. A third movement, the National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA), having fought the MPLA with UNITA during the Angolan War of Independence, played almost no role in the Civil War. Additionally, the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (FLEC), an association of separatist militant groups, fought for the independence of the province of Cabinda from Angola.[citation needed] With the assistance of Cuban soldiers and Soviet support, the MPLA managed to win the initial phase of conventional fighting, oust the FNLA from Luanda, and become the de facto Angolan government.[42] The FNLA disintegrated, but the U.S.- and South Africa-backed UNITA continued its irregular warfare against the MPLA government from its base in the east and south of the country.

The 27-year war can be divided roughly into three periods of major fighting – from 1975 to 1991, 1992 to 1994 and from 1998 to 2002 – with fragile periods of peace. By the time the MPLA achieved victory in 2002, between 500,000 and 800,000 people had died and over one million had been internally displaced.[40][43] The war devastated Angola's infrastructure and severely damaged public administration, the economy, and religious institutions.

The Angolan Civil War was notable due to the combination of Angola's violent internal dynamics and the exceptional degree of foreign military and political involvement. The war is widely considered a Cold War proxy conflict, as the Soviet Union and the United States, with their respective allies Cuba and South Africa, assisted the opposing factions.[44] The conflict became closely intertwined with the Second Congo War in the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo and the South African Border War. Land mines still litter the countryside and contribute to the ongoing civilian casualties.[40]

Main combatants

Angola's three rebel movements had their roots in the anti-colonial movements of the 1950s.[44] The MPLA was primarily an urban-based movement in Luanda and its surrounding area.[44] It was largely composed of Mbundu people. By contrast, the other two major anti-colonial movements, the FNLA and UNITA, were rural groups.[44] The FNLA primarily consisted of Bakongo people from Northern Angola. UNITA, an offshoot of the FNLA, was mainly composed of Ovimbundu people, Angola's largest ethnic group, from the Bié Plateau.[44]

MPLA

Main article: MPLA

Since its formation in the 1950s, the MPLA's main social base has been among the Ambundu people and the multiracial intelligentsia of cities such as Luanda, Benguela and Huambo.[note 3] During its anti-colonial struggle of 1962–1974, the MPLA was supported by several African countries and the Soviet Union. Cuba became the MPLA's strongest ally, sending significant combat and support personnel contingents to Angola. This support, as well as that of several other countries of the Eastern Bloc, e.g. East Germany,[45] was maintained during the Civil War. Yugoslavia provided financial military support for the MPLA, including $14 million in 1977, as well as Yugoslav security personnel in the country and diplomatic training for Angolans in Belgrade.[46] The United States Ambassador to Yugoslavia wrote of the Yugoslav relationship with the MPLA and remarked, "Tito clearly enjoys his role as patriarch of guerrilla liberation struggle." Agostinho Neto, MPLA's leader during the civil war, declared in 1977 that Yugoslav aid was constant and firm and described the help as extraordinary.[47] According to a November 1978 special communique, Portuguese troops were among the 20,000 MPLA troops that participated in a major offensive in central and southern Angola.[48]

FNLA

Main article: National Liberation Front of Angola

The FNLA formed parallel to the MPLA[49] and was initially devoted to defending the interests of the Bakongo people and supporting the restoration of the historical Kongo Empire. It rapidly developed into a nationalist movement, supported in its struggle against Portugal by the government of Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire. During 1974, the FNLA was also briefly supported by the People's Republic of China; but the aid was quickly withdrawn since China mainly supported the UNITA during the Angolan War of Independence. The United States refused to support the FNLA during the movement's war against Portugal, a NATO member but agreed during the civil war.[citation needed]

UNITA

Main article: UNITA

UNITA's main social basis were the Ovimbundu of central Angola, who constituted about one-third of the country's population, but the organization also had roots among several less numerous peoples of eastern Angola. UNITA was founded in 1966 by Jonas Savimbi, who until then had been a prominent leader of the FNLA. During the anti-colonial war, UNITA received some support from the People's Republic of China. With the onset of the civil war, the United States decided to support UNITA and considerably augmented their aid to UNITA in the following decades. In the latter period, UNITA's main ally was the apartheid regime of South Africa.[50][51]

Roots of the conflict

Main articles: History of Angola and Portuguese West Africa

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Angola, like most African countries, became constituted as a nation through colonial intervention. Angola's colonial power was Portugal, which was present and active in the territory, in one way or another, for over four centuries.

Ethnic divisions

Map of Angola's major ethnic groups, c.1970

The original population of this territory were dispersed Khoisan groups. These were absorbed or pushed southwards, where residual groups still exist, by a massive influx of Bantu people who came from the north and east.

The Bantu influx began around 500 BC, and some continued their migrations inside the territory well into the 20th century. They established a number of major political units, of which the most important was the Kongo Empire, whose centre was located in the northwest of what today is Angola and which stretched northwards into the west of the present Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the south and west of the contemporary Republic of Congo and even the southernmost part of Gabon.

Also of historical importance were the Ndongo and Matamba kingdoms to the south of the Kongo Empire, in the Ambundu area. Additionally, the Lunda Empire occupied a portion of north-eastern Angola in the south-east of the present-day DRC. In the south of the territory, and the north of present-day Namibia, lay the Kwanyama kingdom, along with minor realms on the central highlands. All these political units were a reflection of ethnic cleavages that slowly developed among the Bantu populations and were instrumental in consolidating these cleavages and fostering the emergence of new and distinct social identities.

Portuguese colonialism

At the end of the 15th century, Portuguese settlers made contact with the Kongo Empire, maintaining a continuous presence in its territory and enjoying considerable cultural and religious influence after that. In 1575, Portugal established a settlement and fort called Saint Paul of Luanda on the coast south of the Kongo Empire, in an area inhabited by Ambundu people. Another fort, Benguela, was established on the coast further south, in a region inhabited by ancestors of the Ovimbundu people.

Neither of these Portuguese settlement efforts was launched for the purpose of territorial conquest. Both gradually came to occupy and farm a broad area around their initial bridgeheads (in the case of Luanda, mostly along the lower Kwanza River). Their main function was in the Atlantic slave trade. Slaves were bought from African intermediaries and sold to Portuguese colonies in Brazil and the Caribbean. In addition, Benguela developed commerce in ivory, wax, and honey, which they bought from Ovimbundu caravans which fetched these goods from among the Ganguela peoples in the eastern part of what is now Angola.[note 4]

Portuguese colonies in Africa at the time of the Portuguese Colonial War (1961–1974)

Nonetheless, the Portuguese presence on the Angolan coast remained limited for much of the colonial period. The degree of real colonial settlement was minor, and, with few exceptions, the Portuguese did not interfere by means other than commercial in the social and political dynamics of the native peoples. There was no real delimitation of territory; Angola, to all intents and purposes, did not yet exist.

In the 19th century, the Portuguese began a more serious program of advancing into the continental interior. They wanted a de facto overlordship that allowed them to establish commercial networks and a few settlements. In this context, they also moved further south along the coast and founded the "third bridgehead" of Moçâmedes. In the course of this expansion, they entered into conflict with several of the African political units.[52]

Territorial occupation only became a central concern for Portugal in the last decades of the 19th century, during the European powers' "Scramble for Africa", especially following the 1884 Berlin Conference. Several military expeditions were organized as preconditions for obtaining territory, which roughly corresponded to present-day Angola. By 1906, about 6% of that territory was effectively occupied, and the military campaigns had to continue. By the mid-1920s, the limits of the territory were finally fixed, and the last "primary resistance" was quelled in the early 1940s. It is thus reasonable to talk of Angola as a defined territorial entity from this point onwards.

Build-up to independence and rising tensions

Portuguese Army soldiers operating in the Angolan jungle in the early 1960s

In 1961, the FNLA and the MPLA, based in neighbouring countries, began a guerrilla campaign against Portuguese rule on several fronts. The Portuguese Colonial War, which included the Angolan War of Independence, lasted until the Portuguese regime's overthrow in 1974 through a leftist military coup in Lisbon. When the timeline for independence became known, most of the roughly 500,000 ethnic Portuguese Angolans fled the territory during the weeks before or after that deadline. Portugal left behind a newly independent country whose population was mainly composed of Ambundu, Ovimbundu, and Bakongo peoples. The Portuguese that lived in Angola accounted for the majority of the skilled workers in public administration, agriculture, and industry; once they fled the country, the national economy began to sink into depression.[53]

The South African government initially became involved in an effort to counter the Chinese presence in Angola, which was feared might escalate the conflict into a local theatre of the Cold War. In 1975, South African Prime Minister B.J. Vorster authorized Operation Savannah,[54] which began as an effort to protect engineers constructing the dam at Calueque after unruly UNITA soldiers took over. The dam, paid for by South Africa, was felt to be at risk.[55] The South African Defence Force (SADF) dispatched an armoured task force to secure Calueque. From this, Operation Savannah escalated; no formal government was in place and thus, no clear lines of authority.[56] The South Africans came to commit thousands of soldiers to the intervention and ultimately clashed with Cuban forces assisting the MPLA.

1970s

Main article: 1970s in Angola

Independence

After the Carnation Revolution in Lisbon and the end of the Angolan War of Independence, the parties of the conflict signed the Alvor Accords on 15 January 1975. In July 1975, the MPLA violently forced the FNLA out of Luanda, and UNITA voluntarily withdrew to its stronghold in the south. By August, the MPLA had control of 11 of the 15 provincial capitals, including Cabinda and Luanda. South Africa intervened on 23 October, sending between 1,500 and 2,000 troops from Namibia into southern Angola in order to support the FNLA and UNITA. Zaire, in a bid to install a pro-Kinshasa government and thwart the MPLA's drive for power, deployed armored cars, paratroopers, and three infantry battalions to Angola in support of the FNLA.[57] Within three weeks, South African and UNITA forces had captured five provincial capitals, including Novo Redondo and Benguela. In response to the South African intervention, Cuba sent 18,000 soldiers as part of a large-scale military intervention nicknamed Operation Carlota in support of the MPLA. Cuba had initially provided the MPLA with 230 military advisers prior to the South African intervention.[58] The Cuban intervention proved decisive in repelling the South African-UNITA advance. The FNLA were likewise routed at the Battle of Quifangondo and forced to retreat towards Zaire.[59][60] The defeat of the FNLA allowed the MPLA to consolidate power over the capital Luanda.

Burning MPLA staff car destroyed in the fighting outside Novo Redondo, late 1975

Agostinho Neto, the leader of the MPLA, declared the independence of the Portuguese Overseas Province of Angola as the People's Republic of Angola on 11 November 1975.[61] UNITA declared Angolan independence as the Social Democratic Republic of Angola based in Huambo, and the FNLA declared the Democratic Republic of Angola based in Ambriz. FLEC, armed and backed by the French government, declared the independence of the Republic of Cabinda from Paris.[62] The FNLA and UNITA forged an alliance on 23 November, proclaiming their own coalition government, the Democratic People's Republic of Angola, based in Huambo[63] with Holden Roberto and Jonas Savimbi as co-Presidents, and José Ndelé and Johnny Pinnock Eduardo as co-Prime Ministers.[64]

In early November 1975, the South African government warned Savimbi and Roberto that the South African Defence Force (SADF) would soon end operations in Angola despite the failure of the coalition to capture Luanda and therefore secure international recognition for their government. Savimbi, desperate to avoid the withdrawal of South Africa, asked General Constand Viljoen to arrange a meeting for him with Prime Minister of South Africa John Vorster, who had been Savimbi's ally since October 1974. On the night of 10 November, the day before the formal declaration of independence, Savimbi secretly flew to Pretoria to meet Vorster. In a reversal of policy, Vorster not only agreed to keep his troops in Angola through November, but also promised to withdraw the SADF only after the OAU meeting on 9 December.[65][66] While Cuban officers led the mission and provided the bulk of the troop force, 60 Soviet officers in the Congo joined the Cubans on 12 November. The Soviet leadership expressly forbade the Cubans from intervening in Angola's civil war, focusing the mission on containing South Africa.[67]

In 1975 and 1976 most foreign forces, with the exception of Cuba, withdrew. The last elements of the Portuguese military withdrew in 1975[68] and the South African military withdrew in February 1976.[69] Cuba's troop force in Angola increased from 5,500 in December 1975 to 11,000 in February 1976.[70]

Sweden provided humanitarian assistance to both the SWAPO and the MPLA in the mid-1970s,[71][72][73] and regularly raised the issue of UNITA in political discussions between the two movements.

Cuban intervention

Main article: Cuban intervention in Angola

Location of Cuba (red), Angola (green), and South Africa (blue)

Cuban logistics were primitive, relying on a few aging commercial aircraft, small cargo ships, and large fishing vessels to support a major, long-range military operation.[74]

In early September 1975, the Cuban merchant ships Viet Nam Heroico, Isla Coral, and La Plata, loaded with troops, vehicles, and 1,000 tons of gasoline, crossed the Atlantic and sailed to Angola. The United States held a secret, high-level talk with Cuba to express its consternation over Cuba's actions, but this had little effect. The Cuban troops landed in early October. On 7 November, Cuba began a thirteen-day airlift of a 650-man special forces battalion. The Cubans used old Bristol Britannia turboprop aircraft, making refueling stops in Barbados, Guinea-Bissau, and the Congo before landing in Luanda. The troops traveled as "tourists," carrying machine guns in briefcases. They packed 75mm cannons, 82mm mortars, and small arms into the aircraft's cargo holds.[74]

On 14 October, four South African columns totaling 3,000 troops launched Operation Savannah in an attempt to capture Luanda from the south. The Cubans suffered major reversals, including one at Catofe, where South African forces surprised them and caused numerous casualties.[34] However, the Cubans ultimately halted the South African advance by 26 November.[32] Later, another 4,000 South African soldiers entered southern Angola to establish a buffer zone along the Namibian border. The MPLA received support from 3,000 Katangan exiles, a Mozambican battalion, 3,000 East German personnel, and 1,000 Soviet advisors. The pivotal intervention came from 18,000 Cuban troops, who defeated the FNLA in the north and UNITA in the south, concluding the conventional war by 12 February 1976.[32] In Cabinda, the Cubans launched a series of successful operations against the FLEC separatist movement.[75]

By March 1977, the MPLA controlled enough of the country to permit Castro to pay a state visit. However, in May, Nito Alves and José Van Dunem attempted an unsuccessful coup against Agostinho Neto. Cuban troops helped defeat the rebels.[74] In May 1978, South Africa initiated Operation Reindeer, during which an airstrike on a Cuban convoy resulted in the loss of 150 Cuban troops. By July 1978, Cuba had suffered 5,600 casualties in its African wars (Angola and Ethiopia), including 1,000 killed in Angola and 400 killed against Somali forces in the Ethiopian Ogaden.[32] In 1987, 6,000 South African soldiers reentered the Angolan war, clashing with Cuban forces. They defeated four MPLA brigades at the Lomba River in September and laid siege to Cuito Cuanavale for months until 12,000 Cuban troops broke the blockade in March 1988.[32] On 26 June, South African forces engaged Cuban forces at Techipa, killing several Cuban troops. In response, Cuba launched an air strike on SADF positions the following day, killing nearly a dozen South African troops. Both sides promptly withdrew to prevent further escalation of hostilities.

Clark Amendment

Main articles: Operation IA Feature and Clark Amendment

President of the United States Gerald Ford approved covert aid to UNITA and the FNLA through Operation IA Feature on 18 July 1975, despite strong opposition from officials in the State Department and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Ford told William Colby, the Director of Central Intelligence, to establish the operation, providing an initial US$6 million. He granted an additional $8 million on 27 July and another $25 million in August.[76][77]

Senator Dick Clark

Two days before the program's approval, Nathaniel Davis, the Assistant Secretary of State, told Henry Kissinger, the Secretary of State, that he believed maintaining the secrecy of IA Feature would be impossible. Davis correctly predicted the Soviet Union would respond by increasing involvement in the Angolan conflict, leading to more violence and negative publicity for the United States. When Ford approved the program, Davis resigned.[78] John Stockwell, the CIA's station chief in Angola, echoed Davis' criticism saying that success required the expansion of the program, but its size already exceeded what could be hidden from the public eye. Davis' deputy, former U.S. ambassador to Chile Edward Mulcahy, also opposed direct involvement. Mulcahy presented three options for U.S. policy towards Angola on 13 May 1975. Mulcahy believed the Ford administration could use diplomacy to campaign against foreign aid to the communist MPLA, refuse to take sides in factional fighting, or increase support for the FNLA and UNITA. He warned that supporting UNITA would not sit well with Mobutu Sese Seko, the president of Zaire.[76][79]

Dick Clark, a Democratic Senator from Iowa, discovered the operation during a fact-finding mission in Africa, but Seymour Hersh, a reporter for The New York Times, revealed IA Feature to the public on 13 December 1975.[80] Clark proposed an amendment to the Arms Export Control Act, barring aid to private groups engaged in military or paramilitary operations in Angola. The Senate passed the bill, voting 54–22 on 19 December 1975, and the House of Representatives passed the bill, voting 323–99 on 27 January 1976.[77] Ford signed the bill into law on 9 February 1976.[81] Even after the Clark Amendment became law, then-Director of Central Intelligence, George H. W. Bush, refused to concede that all U.S. aid to Angola had ceased.[82][83] According to foreign affairs analyst Jane Hunter, Israel stepped in as a proxy arms supplier for South Africa after the Clark Amendment took effect.[84] Israel and South Africa established a longstanding military alliance, in which Israel provided weapons and training, as well as conducting joint military exercises.[85]

The U.S. government vetoed Angolan entry into the United Nations on 23 June 1976.[86] Zambia forbade UNITA from launching attacks from its territory on 28 December 1976[87] after Angola under MPLA rule became a member of the United Nations.[88] According to Ambassador William Scranton, the United States abstained from voting on the issue of Angola becoming a UN member state "out of respect for the sentiments expressed by its [our] African friends".[89]

Shaba invasions

Main articles: Shaba I and Shaba II

Shaba Province, Zaire

About 1,500 members of the Congolese National Liberation Front (FNLC) invaded the Shaba Province (modern-day Katanga Province) in Zaire from eastern Angola on 7 March 1977. The FNLC wanted to overthrow Mobutu, and the MPLA government, suffering from Mobutu's support for the FNLA and UNITA, did not try to stop the invasion. The FNLC failed to capture Kolwezi, Zaire's economic heartland, but took Kasaji and Mutshatsha. The Zairean army (the Forces Armées Zaïroises) was defeated without difficulty and the FNLC continued to advance. On 2 April, Mobutu appealed to William Eteki of Cameroon, Chairman of the Organization of African Unity, for assistance. Eight days later, the French government responded to Mobutu's plea and airlifted 1,500 Moroccan troops into Kinshasa. This force worked in conjunction with the Zairean army, the FNLA[90] and Egyptian pilots flying French-made Zairean Mirage fighter aircraft to beat back the FNLC. The counter-invasion force pushed the last of the militants, along with numerous refugees, into Angola and Zambia in April 1977.[91][92][93][94]

Mobutu accused the MPLA, Cuban and Soviet governments of complicity in the war.[95] While Neto did support the FNLC, the MPLA government's support came in response to Mobutu's continued support for Angola's FNLA.[96] The Carter Administration, unconvinced of Cuban involvement, responded by offering a meager $15 million-worth of non-military aid. American timidity during the war prompted a shift in Zaire's foreign policy towards greater engagement with France, which became Zaire's largest supplier of arms after the intervention.[97] Neto and Mobutu signed a border agreement on 22 July 1977.[98]

John Stockwell, the CIA's station chief in Angola, resigned after the invasion, explaining in the April 1977 The Washington Post article "Why I'm Leaving the CIA" that he had warned Secretary of State Henry Kissinger that continued American support for anti-government rebels in Angola could provoke a war with Zaire. He also said that covert Soviet involvement in Angola came after, and in response to, U.S. involvement.[99]

The FNLC invaded Shaba again on 11 May 1978, capturing Kolwezi in two days. While the Carter Administration had accepted Cuba's insistence on its non-involvement in Shaba I, and therefore did not stand with Mobutu, the U.S. government now accused Castro of complicity.[100] This time, when Mobutu appealed for foreign assistance, the U.S. government worked with the French and Belgian militaries to beat back the invasion, the first military cooperation between France and the United States since the Vietnam War.[101][102] The French Foreign Legion took back Kolwezi after a seven-day battle and airlifted 2,250 European citizens to Belgium, but not before the FNLC massacred 80 Europeans and 200 Africans. In one instance, the FNLC killed 34 European civilians who had hidden in a room. The FNLC retreated to Zambia, vowing to return to Angola. The Zairean army then forcibly evicted civilians along Shaba's border with Angola. Mobutu, wanting to prevent any chance of another invasion, ordered his troops to shoot on sight.[103]

U.S.-mediated negotiations between the MPLA and Zairean governments led to a peace accord in 1979 and an end to support for insurgencies in each other's respective countries. Zaire temporarily cut off support to the FLEC, the FNLA and UNITA, and Angola forbade further activity by the FNLC.[101]

Nitistas

Main articles: 1970s in Angola and 1977 Angolan coup d'état attempt

By the late 1970s, Interior Minister Nito Alves had become a powerful member of the MPLA government. Alves had successfully put down Daniel Chipenda's Eastern Revolt and the Active Revolt during Angola's War of Independence. Factionalism within the MPLA became a major challenge to Neto's power by late 1975 and Neto gave Alves the task of once again clamping down on dissent. Alves shut down the Cabral and Henda Committees while expanding his influence within the MPLA through his control of the nation's newspapers and state-run television. Alves visited the Soviet Union in October 1976, and may have obtained Soviet support for a coup against Neto. By the time he returned, Neto had grown suspicious of Alves' growing power and sought to neutralize him and his followers, the Nitistas. Neto called a plenum meeting of the Central Committee of the MPLA. Neto formally designated the party as Marxist-Leninist, abolished the Interior Ministry (of which Alves was the head), and established a Commission of Enquiry. Neto used the commission to target the Nitistas, and ordered the commission to issue a report of its findings in March 1977. Alves and Chief of Staff José Van-Dunem, his political ally, began planning a coup d'état against Neto.[104]

Agostinho Neto, MPLA leader and Angola's first president, meets with Poland's ambassador in Luanda, 1978

Alves and Van-Dunem planned to arrest Neto on 21 May before he arrived at a meeting of the Central Committee and before the commission released its report on the activities of the Nitistas. The MPLA changed the location of the meeting shortly before its scheduled start, throwing the plotters' plans into disarray. Alves attended anyway. The commission released its report, accusing him of factionalism. Alves fought back, denouncing Neto for not aligning Angola with the Soviet Union. After twelve hours of debate, the party voted 26 to 6 to dismiss Alves and Van-Dunem from their positions.[104]

In support of Alves and the coup, the People's Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) 8th Brigade broke into São Paulo prison on 27 May, killing the prison warden and freeing more than 150 Nitistas. The 8th brigade then took control of the radio station in Luanda and announced their coup, calling themselves the MPLA Action Committee. The brigade asked citizens to show their support for the coup by demonstrating in front of the presidential palace. The Nitistas captured Bula and Dangereaux, generals loyal to Neto, but Neto had moved his base of operations from the palace to the Ministry of Defence in fear of such an uprising. Cuban troops loyal to Neto retook the palace and marched to the radio station. The Cubans succeeded in taking the radio station and proceeded to the barracks of the 8th Brigade, recapturing it by 1:30 pm. While the Cuban force captured the palace and radio station, the Nitistas kidnapped seven leaders within the government and the military, shooting and killing six.[105]

The MPLA government arrested tens of thousands of suspected Nitistas from May to November and tried them in secret courts overseen by Defense Minister Iko Carreira. Those who were found guilty, including Van-Dunem, Jacobo "Immortal Monster" Caetano, the head of the 8th Brigade, and political commissar Eduardo Evaristo, were shot and buried in secret graves. At least 2,000 followers (or alleged followers) of Nito Alves were estimated to have been killed by Cuban and MPLA troops in the aftermath, with some estimates claiming as high as 90,000 dead. Amnesty International estimated 30,000 died in the purge.[106][107][108][109]

The coup attempt had a lasting effect on Angola's foreign relations. Alves had opposed Neto's foreign policy of non-alignment, evolutionary socialism, and multiracialism, favoring stronger relations with the Soviet Union, which Alves wanted to grant military bases in Angola. While Cuban soldiers actively helped Neto put down the coup, Alves and Neto both believed the Soviet Union opposed Neto. Cuban Armed Forces Minister Raúl Castro sent an additional four thousand troops to prevent further dissension within the MPLA's ranks and met with Neto in August in a display of solidarity. In contrast, Neto's distrust of the Soviet leadership increased and relations with the USSR worsened.[105] In December, the MPLA held its first party Congress and changed its name to the MPLA-Worker's Party (MPLA-PT). The Nitista attempted coup took a toll on the MPLA's membership. In 1975, the MPLA had reached 200,000 members, but after the first party congress, that number decreased to 30,000.[104][110][111][112][113]

Replacing Neto

The Soviets tried to increase their influence, wanting to establish permanent military bases in Angola,[114] but despite persistent lobbying, especially by the Soviet chargé d'affaires, G. A. Zverev, Neto stood his ground and refused to allow the construction of permanent military bases. With Alves no longer a possibility, the Soviet Union backed Prime Minister Lopo do Nascimento against Neto for the MPLA's leadership.[115] Neto moved swiftly, getting the party's Central Committee to fire Nascimento from his posts as Prime Minister, Secretary of the Politburo, Director of National Television, and Director of Jornal de Angola. Later that month, the positions of Prime Minister and Deputy Prime Minister were abolished.[116]

Neto diversified the ethnic composition of the MPLA's political bureau as he replaced the hardline old guard with new blood, including José Eduardo dos Santos.[117] When he died on 10 September 1979, the party's Central Committee unanimously voted to elect dos Santos as President.[citation needed]

1980s

Main article: 1980s in Angola

South African paratroopers on patrol near the border region, mid-1980s.

Under dos Santos's leadership, Angolan troops crossed the border into Namibia for the first time on 31 October, going into Kavango. The next day, dos Santos signed a non-aggression pact with Zambia and Zaire.[118] In the 1980s, fighting spread outward from southeastern Angola, where most of the fighting had taken place in the 1970s, as the National Congolese Army (ANC) and SWAPO increased their activity. The South African government responded by sending troops back into Angola, intervening in the war from 1981 to 1987,[69] prompting the Soviet Union to deliver massive amounts of military aid from 1981 to 1986. The USSR gave the MPLA more than US$2 billion in aid in 1984.[119] In 1981, newly elected United States President Ronald Reagan's U.S. assistant secretary of state for African affairs, Chester Crocker, developed a linkage policy, tying Namibian independence to Cuban withdrawal and peace in Angola.[120][121]

Beginning with 1979, Romania trained Angolan guerrillas. Every 3–4 months, Romania sent two airplanes to Angola, each returning with 166 recruits. These were taken back to Angola after they completed their training. In addition to guerrilla training, Romania also instructed young Angolans as pilots. In 1979, under the command of Major General Aurel Niculescu [ro], Romania founded an air academy in Angola. There were around 100 Romanian instructors in this academy, with about 500 Romanian soldiers guarding the base, which supported 50 aircraft used to train Angolan pilots. The aircraft models used were: IAR 826, IAR 836, EL-29, MiG-15 and AN-24.[122][123] Designated as the "Commander Bula National Military Aviation School", it was set up on 11 February 1981 in Negage. The facility trained air force pilots, technicians and General Staff officers. The Romanian teaching staff was gradually replaced by Angolans.[124]

The South African military attacked insurgents in Cunene Province on 12 May 1980. The Angolan Ministry of Defense accused the South African government of wounding and killing civilians. Nine days later, the SADF attacked again, this time in Cuando-Cubango, and the MPLA threatened to respond militarily. The SADF launched a full-scale invasion of Angola through Cunene and Cuando-Cubango on 7 June, destroying SWAPO's operational command headquarters on 13 June, in what Prime Minister Pieter Willem Botha described as a "shock attack". The MPLA government arrested 120 Angolans who were planning to set off explosives in Luanda, on 24 June, foiling a plot purportedly orchestrated by the South African government. Three days later, the United Nations Security Council convened at the behest of Angola's ambassador to the UN, E. de Figuerido, and condemned South Africa's incursions into Angola. President Mobutu of Zaire also sided with the MPLA. The MPLA government recorded 529 instances in which they claim South African forces violated Angola's territorial sovereignty between January and June 1980.[125]

Cuba increased its troop force in Angola from 35,000 in 1982 to 40,000 in 1985. South African forces tried to capture Lubango, capital of Huíla province, in Operation Askari in December 1983.[120]

In 1984, five Mexican nationals (who are doing missionary work) were kidnapped by UNITA in 1984. The nuns were later released through negotiations by the International Red Cross. In response to the incident, Mexican Foreign Minister Bernardo Sepúlveda Amor had visited Angola in 1985 to support the MPLA to (both diplomatically and militarily) protect Mexican nationals.[18]

On 2 June 1985, American conservative activists held the Democratic International, a symbolic meeting of anti-Communist militants, at UNITA's headquarters in Jamba.[126] Primarily funded by Rite Aid founder Lewis Lehrman and organized by anti-communist activists Jack Abramoff and Jack Wheeler, participants included Savimbi, Adolfo Calero, leader of the Nicaraguan Contras, Pa Kao Her, Hmong Laotian rebel leader, U.S. Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, South African security forces, Abdurrahim Wardak, Afghan Mujahideen leader, Jack Wheeler, American conservative policy advocate, and many others.[127] The Reagan administration, although unwilling to publicly support the meeting, privately expressed approval. The governments of Israel and South Africa supported the idea, but both respective countries were deemed inadvisable for hosting the conference.[127]

The participants released a communiqué stating,

We, free peoples fighting for our national independence and human rights, assembled at Jamba, declare our solidarity with all freedom movements in the world and state our commitment to cooperate to liberate our nations from the Soviet Imperialists.

The United States House of Representatives voted 236 to 185 to repeal the Clark Amendment on 11 July 1985.[128] The MPLA government began attacking UNITA later that month from Luena towards Cazombo along the Benguela Railway in a military operation named Congresso II, taking Cazombo on 18 September. The MPLA government tried unsuccessfully to take UNITA's supply depot in Mavinga from Menongue. While the attack failed, very different interpretations of the attack emerged. UNITA claimed Portuguese-speaking Soviet officers led FAPLA troops while the government said UNITA relied on South African paratroopers to defeat the MPLA attack. The South African government admitted to fighting in the area, but said its troops fought SWAPO militants.[129]

War intensifies

By 1986, Angola began to assume a more central role in the Cold War, with the Soviet Union, Cuba and other Eastern bloc nations enhancing support for the MPLA government, and American conservatives beginning to elevate their support for Savimbi's UNITA. Savimbi developed close relations with influential American conservatives, who saw Savimbi as a key ally in the U.S. effort to oppose and rollback Soviet-backed, undemocratic governments around the world. The conflict quickly escalated, with both Washington and Moscow seeing it as a critical strategic conflict in the Cold War.[citation needed]

Maximum extent of South African and UNITA operations in Angola and Zambia

The Soviet Union gave an additional $1 billion in aid to the MPLA government and Cuba sent an additional 2,000 troops to the 35,000-strong force in Angola to protect Chevron oil platforms in 1986.[129] Savimbi had called Chevron's presence in Angola, already protected by Cuban troops, a "target" for UNITA in an interview with Foreign Policy magazine on 31 January.[130]

In Washington, Savimbi forged close relationships with influential conservatives, including Michael Johns (The Heritage Foundation's foreign policy analyst and a key Savimbi advocate), Grover Norquist (President of Americans for Tax Reform and a Savimbi economic advisor), and others, who played critical roles in elevating escalated U.S. covert aid to Savimbi's UNITA and visited with Savimbi in his Jamba, Angola headquarters to provide the Angolan rebel leader with military, political and other guidance in his war against the MPLA government. With enhanced U.S. support, the war quickly escalated, both in terms of the intensity of the conflict and also in its perception as a key conflict in the overall Cold War.[131][132]

In addition to escalating its military support for UNITA, the Reagan administration and its conservative allies also worked to expand recognition of Savimbi as a key U.S. ally in an important Cold War struggle. In January 1986, Reagan invited Savimbi to a meeting at the White House. Following the meeting, Reagan spoke of UNITA as winning a victory that "electrifies the world". Two months later, Reagan announced the delivery of Stinger surface-to-air missiles as part of the $25 million in aid UNITA received from the U.S. government.[120][133] Jeremias Chitunda, UNITA's representative to the U.S., became the Vice President of UNITA in August 1986 at the sixth party congress.[134] Fidel Castro made Crocker's proposal—the withdrawal of foreign troops from Angola and Namibia—a prerequisite to Cuban withdrawal from Angola on 10 September.

UNITA forces attacked Camabatela in Cuanza Norte province on 8 February 1986. ANGOP alleged UNITA massacred civilians in Damba in Uíge Province later that month, on 26 February. The South African government agreed to Crocker's terms in principle on 8 March. Savimbi proposed a truce regarding the Benguela railway on 26 March, saying MPLA trains could pass through as long as an international inspection group monitored trains to prevent their use for counter-insurgency activity. The government did not respond. In April 1987, Fidel Castro sent Cuba's Fiftieth Brigade to southern Angola, increasing the number of Cuban troops from 12,000 to 15,000.[135] The MPLA and American governments began negotiating in June 1987.[136][137]

Cuito Cuanavale and New York Accords

Main articles: Battle of Cuito Cuanavale and New York Accords

UNITA and South African forces attacked the MPLA's base at Cuito Cuanavale in Cuando Cubango province from 13 January to 23 March 1988, in the second-largest battle in the history of Africa,[138] after the Battle of El Alamein,[139] the largest in sub-Saharan Africa since World War II.[140] Cuito Cuanavale's importance came not from its size or its wealth but its location. South African Defence Forces maintained an overwatch on the city using new, G5 artillery pieces. Both sides claimed victory in the ensuing Battle of Cuito Cuanavale.[120][141][142][143]

Map of Angola's provinces, with Cuando Cubango province highlighted.

After the indecisive results of the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale, Fidel Castro claimed that the increased cost of continuing to fight for South Africa had placed Cuba in its most aggressive combat position of the war, arguing that he was preparing to leave Angola with his opponents on the defensive. According to Cuba, the political, economic and technical cost to South Africa of maintaining its presence in Angola proved too much. Conversely, the South Africans believe that they indicated their resolve to the superpowers by preparing a nuclear test that ultimately forced the Cubans into a settlement.[144]

Cuban troops were alleged to have used nerve gas against UNITA troops during the civil war. Belgian criminal toxicologist Dr. Aubin Heyndrickx, studied alleged evidence, including samples of war-gas "identification kits" found after the battle at Cuito Cuanavale, claimed that "there is no doubt anymore that the Cubans were using nerve gases against the troops of Mr. Jonas Savimbi."[145]

The Cuban government joined negotiations on 28 January 1988, and all three parties held a round of negotiations on 9 March. The South African government joined negotiations on 3 May and the parties met in June and August in New York and Geneva. All parties agreed to a ceasefire on 8 August. Representatives from the governments of Angola, Cuba, and South Africa signed the New York Accords, granting independence to Namibia and ending the direct involvement of foreign troops in the civil war, in New York City on 22 December 1988.[120][137] The United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 626 later that day, creating the United Nations Angola Verification Mission (UNAVEM), a peacekeeping force. UNAVEM troops began arriving in Angola in January 1989.[146]

Ceasefire

As the Angolan Civil War began to take on a diplomatic component, in addition to a military one, two key Savimbi allies, The Conservative Caucus' Howard Phillips and the Heritage Foundation's Michael Johns visited Savimbi in Angola, where they sought to persuade Savimbi to come to the United States in the spring of 1989 to help the Conservative Caucus, the Heritage Foundation and other conservatives in making the case for continued U.S. aid to UNITA.[147]

President Mobutu invited 18 African leaders, Savimbi, and dos Santos to his palace in Gbadolite in June 1989 for negotiations. Savimbi and dos Santos met for the first time and agreed to the Gbadolite Declaration, a ceasefire, on 22 June, paving the way for a future peace agreement.[148][149] President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia said a few days after the declaration that Savimbi had agreed to leave Angola and go into exile, a claim Mobutu, Savimbi, and the U.S. government disputed.[149] Dos Santos agreed with Kaunda's interpretation of the negotiations, saying Savimbi had agreed to temporarily leave the country.[150]

On 23 August, dos Santos complained that the U.S. and South African governments continued to fund UNITA, warning such activity endangered the already fragile ceasefire. The next day Savimbi announced UNITA would no longer abide by the ceasefire, citing Kaunda's insistence that Savimbi leave the country and UNITA disband. The MPLA government responded to Savimbi's statement by moving troops from Cuito Cuanavale, under MPLA control, to UNITA-occupied Mavinga. The ceasefire broke down with dos Santos and the U.S. government blaming each other for the resumption in armed conflict.[151]

1990s

Main articles: 1990s in Angola, Angolagate, United Nations Angola Verification Mission II, and First Congo War

Political changes abroad and military victories at home allowed the government to transition from a nominally communist state to a nominally democratic one. Namibia's declaration of independence, internationally recognized on 1 April, eliminated the threat to the MPLA from South Africa, as the SADF withdrew from Namibia.[152] The MPLA abolished the one-party system in June and rejected Marxist-Leninism at the MPLA's third Congress in December, formally changing the party's name from the MPLA-PT to the MPLA.[148] The National Assembly passed law 12/91 in May 1991, coinciding with the withdrawal of the last Cuban troops, defining Angola as a "democratic state based on the rule of law" with a multi-party system.[153] Observers met such changes with skepticism. American journalist Karl Maier wrote: "In the New Angola ideology is being replaced by the bottom line, as security and selling expertise in weaponry have become a very profitable business. With its wealth in oil and diamonds, Angola is like a big swollen carcass and the vultures are swirling overhead. Savimbi's former allies are switching sides, lured by the aroma of hard currency."[154] Savimbi also reportedly purged some of those within UNITA whom he may have seen as threats to his leadership or as questioning his strategic course. Among those killed in the purge were Tito Chingunji and his family in 1991. Savimbi denied his involvement in the Chingunji killing and blamed it on UNITA dissidents.[155]

Black, Manafort, and Stone

Main article: Black, Manafort, Stone and Kelly

Building in Huambo showing the effects of war

Government troops wounded Savimbi in battles in January and February 1990, but not enough to restrict his mobility.[156] He went to Washington, D.C., in December and met with President George H. W. Bush again,[148] the fourth of five trips he made to the United States. Savimbi paid Black, Manafort, Stone, and Kelly, a lobbying firm based in Washington, D.C., $5 million to lobby the Federal government for aid, portray UNITA favorably in Western media, and acquire support among politicians in Washington. Savimbi was highly successful in this endeavour. The weapons he would gain from Bush helped UNITA survive even after U.S. support stopped.[157]

Senators Larry Smith and Dante Fascell, a senior member of the firm, worked with the Cuban American National Foundation, Representative Claude Pepper of Florida, Neal Blair's Free the Eagle, and Howard Phillips' Conservative Caucus to repeal the Clark Amendment in 1985.[158] From the amendment's repeal in 1985 to 1992 the U.S. government gave Savimbi $60 million per year, a total of $420 million. A sizable amount of the aid went to Savimbi's personal expenses. Black, Manafort filed foreign lobbying records with the U.S. Justice Department showing Savimbi's expenses during his U.S. visits. During his December 1990 visit he spent $136,424 at the Park Hyatt hotel and $2,705 in tips. He spent almost $473,000 in October 1991 during his week-long visit to Washington and Manhattan. He spent $98,022 in hotel bills, at the Park Hyatt, $26,709 in limousine rides in Washington and another $5,293 in Manhattan. Paul Manafort, a partner in the firm, charged Savimbi $19,300 in consulting and additional $1,712 in expenses. He also bought $1,143 worth of "survival kits" from Motorola. When questioned in an interview in 1990 about human rights abuses under Savimbi, Black said, "Now when you're in a war, trying to manage a war, when the enemy ... is no more than a couple of hours away from you at any given time, you might not run your territory according to New Hampshire town meeting rules."[citation needed]

Bicesse Accords

Main article: Bicesse Accords

President dos Santos met with Savimbi in Lisbon, Portugal and signed the Bicesse Accords, the first of three major peace agreements, on 31 May 1991, with the mediation of the Portuguese government. The accords laid out a transition to multi-party democracy under the supervision of the United Nations' UNAVEM II mission, with a presidential election to be held within a year. The agreement attempted to demobilize the 152,000 active fighters and integrate the remaining government troops and UNITA rebels into a 50,000-strong Angolan Armed Forces (FAA). The FAA would consist of a national army with 40,000 troops, navy with 6,000, and air force with 4,000.[159] While UNITA largely did not disarm, the FAA complied with the accord and demobilized, leaving the government disadvantaged.[160]

Angola held the first round of its 1992 presidential election on 29–30 September. Dos Santos officially received 49.57% of the vote and Savimbi won 40.6%. As no candidate received 50% or more of the vote, election law dictated a second round of voting between the top two contenders. Savimbi, along with eight opposition parties and many other election observers, said the election had been neither free nor fair.[161] An official observer wrote that there was little UN supervision, that 500,000 UNITA voters were disenfranchised and that there were 100 clandestine polling stations.[161][162] Savimbi sent Jeremias Chitunda, Vice President of UNITA, to Luanda to negotiate the terms of the second round.[163][164] The election process broke down on 31 October, when government troops in Luanda attacked UNITA. Civilians, using guns they had received from police a few days earlier, conducted house-by-house raids with the Rapid Intervention Police, killing and detaining hundreds of UNITA supporters. The government took civilians in trucks to the Camama cemetery and Morro da Luz ravine, shot them, and buried them in mass graves. Assailants attacked Chitunda's convoy on 2 November, pulling him out of his car and shooting him and two others in their faces.[164] The MPLA massacred over ten thousand UNITA and FNLA voters nationwide in a few days in what was known as the Halloween Massacre.[161][165] Savimbi said the election had neither been free nor fair and refused to participate in the second round.[163] He then proceeded to resume armed struggle against the MPLA.

Then, in a series of stunning victories, UNITA regained control over Caxito, Huambo, M'banza Kongo, Ndalatando, and Uíge, provincial capitals it had not held since 1976, and moved against Kuito, Luena, and Malange. Although the U.S. and South African governments had stopped aiding UNITA, supplies continued to come from Mobutu in Zaire.[166] UNITA tried to wrest control of Cabinda from the MPLA in January 1993. Edward DeJarnette, Head of the U.S. Liaison Office in Angola for the Clinton Administration, warned Savimbi that, if UNITA hindered or halted Cabinda's production, the U.S. would end its support for UNITA. On 9 January, UNITA began a 55-day battle over Huambo, the "War of the Cities".[167] Hundreds of thousands fled and 10,000 were killed before UNITA gained control on 7 March. The government engaged in an ethnic cleansing of Bakongo, and, to a lesser extent Ovimbundu, in multiple cities, most notably Luanda, on 22 January in the Bloody Friday massacre. UNITA and government representatives met five days later in Ethiopia, but negotiations failed to restore the peace.[168] The United Nations Security Council sanctioned UNITA through Resolution 864 on 15 September 1993, prohibiting the sale of weapons or fuel to UNITA.

Perhaps the clearest shift in U.S. foreign policy emerged when President Bill Clinton issued Executive Order 12865 on 23 September, labeling UNITA a "continuing threat to the foreign policy objectives of the U.S."[169] By August 1993, UNITA had gained control over 70% of Angola, but the government's military successes in 1994 forced UNITA to sue for peace. By November 1994, the government had taken control of 60% of the country. Savimbi called the situation UNITA's "deepest crisis" since its creation.[154][170][171] It is estimated that perhaps 120,000 people were killed in the first eighteen months following the 1992 election, nearly half the number of casualties of the previous sixteen years of war.[172] Both sides of the conflict continued to commit widespread and systematic violations of the laws of war with UNITA in particular guilty of indiscriminate shelling of besieged cities resulting in large death toll to civilians. The MPLA government forces used air power in indiscriminate fashion also resulting in high civilian deaths.[173] The Lusaka Protocol of 1994 reaffirmed the Bicesse Accords.[174]

Lusaka Protocol

Main article: Lusaka Protocol

Savimbi, unwilling to personally sign an accord, had former UNITA Secretary General Eugenio Manuvakola represent UNITA in his place. Manuvakola and Angolan Foreign Minister Venancio de Moura signed the Lusaka Protocol in Lusaka, Zambia on 31 October 1994, agreeing to integrate and disarm UNITA. Both sides signed a ceasefire as part of the protocol on 20 November.[170][171] Under the agreement the government and UNITA would cease fire and demobilize. 5,500 UNITA members, including 180 militants, would join the Angolan national police, 1,200 UNITA members, including 40 militants, would join the rapid reaction police force, and UNITA generals would become officers in the Angolan Armed Forces. Foreign mercenaries would return to their home countries and all parties would stop acquiring foreign arms. The agreement gave UNITA politicians homes and a headquarters. The government agreed to appoint UNITA members to head the Mines, Commerce, Health, and Tourism ministries, in addition to seven deputy ministers, ambassadors, the governorships of Uige, Lunda Sul, and Cuando Cubango, deputy governors, municipal administrators, deputy administrators, and commune administrators. The government would release all prisoners and give amnesty to all militants involved in the civil war.[170][171] Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe and South African President Nelson Mandela met in Lusaka on 15 November 1994 to boost support symbolically for the protocol. Mugabe and Mandela both said they would be willing to meet with Savimbi and Mandela asked him to come to South Africa, but Savimbi did not come. The agreement created a joint commission, consisting of officials from the Angolan government, UNITA, and the UN with the governments of Portugal, the United States, and Russia observing, to oversee its implementation. Violations of the protocol's provisions would be discussed and reviewed by the commission.[170] The protocol's provisions, integrating UNITA into the military, a ceasefire, and a coalition government, were similar to those of the Alvor Agreement that granted Angola independence from Portugal in 1975. Many of the same environmental problems, mutual distrust between UNITA and the MPLA, loose international oversight, the importation of foreign arms, and an overemphasis on maintaining the balance of power, led to the collapse of the protocol.[171]

Arms monitoring

Decommissioned UNITA BMP-1 and BM-21 Grads at an assembly point.

In January 1995, U.S. President Clinton sent Paul Hare, his envoy to Angola, to support the Lusaka Protocol and impress the importance of the ceasefire onto the Angolan government and UNITA, both in need of outside assistance.[175] The United Nations agreed to send a peacekeeping force on 8 February.[69] Savimbi met with South African President Mandela in May. Shortly after, on 18 June, the MPLA offered Savimbi the position of Vice President under dos Santos with another Vice President chosen from the MPLA. Savimbi told Mandela he felt ready to "serve in any capacity which will aid my nation," but he did not accept the proposal until 12 August.[176][177] The United States Department of Defense and Central Intelligence Agency's Angola operations and analysis expanded in an effort to halt weapons shipments,[175] a violation of the protocol, with limited success. The Angolan government bought six Mil Mi-17 from Ukraine in 1995.[178] The government bought L-39 attack aircraft from the Czech Republic in 1998 along with ammunition and uniforms from Zimbabwe Defence Industries and ammunition and weapons from Ukraine in 1998 and 1999.[178] U.S. monitoring significantly dropped off in 1997 as events in Zaire, the Congo and then Liberia occupied more of the U.S. government's attention.[175] UNITA purchased more than 20 FROG-7 transporter erector launchers (TEL) and three FOX 7 missiles from the North Korean government in 1999.[179]

The UN extended its mandate on 8 February 1996. In March, Savimbi and dos Santos formally agreed to form a coalition government.[69] The government deported 2,000 West African and Lebanese Angolans in Operation Cancer Two, in August 1996, on the grounds that dangerous minorities were responsible for the rising crime rate.[180] In 1996 the Angolan government bought military equipment from India, two Mil Mi-24 attack helicopters and three Sukhoi Su-17 from Kazakhstan in December, and helicopters from Slovakia in March.[178]

The international community helped install a Government of Unity and National Reconciliation in April 1997, but UNITA did not allow the regional MPLA government to take up residence in 60 cities. The UN Security Council voted on 28 August 1997, to impose sanctions on UNITA through Resolution 1127, prohibiting UNITA leaders from traveling abroad, closing UNITA's embassies abroad, and making UNITA-controlled areas a no-fly zone. The Security Council expanded the sanctions through Resolution 1173 on 12 June 1998, requiring government certification for the purchase of Angolan diamonds and freezing UNITA's bank accounts.[166]

During the First Congo War, the Angolan government joined the coalition to overthrow Mobutu's government due to his support for UNITA. Mobutu's government fell to the opposition coalition on 16 May 1997.[181] The Angolan government chose to act primarily through Katangese gendarmes called the Tigres, which were proxy groups formed from the descendants of police units who had been exiled from Zaire and thus were fighting for a return to their homeland.[182] Luanda

-

3:01:13

3:01:13

The Memory Hole

1 month agoWatergate Hearings Day 43: John R. "Fat Jack" Buckley (1973-10-09)

567 -

![Days Gone: Old Country Road - Part 3 [PC] | Rumble Gaming](https://1a-1791.com/video/s8/1/Q/q/G/_/QqG_u.0kob-small-Days-Gone-Old-Country-Road-.jpg) LIVE

LIVE

NeoX5

2 hours agoDays Gone: Old Country Road - Part 3 [PC] | Rumble Gaming

268 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

CAMELOT331

2 hours agoRide N' Die 24 Hour LAUNCH Ft Ethan Van Sciver, Cecil, ItsaGundam, That Star Wars Girl, Shane & MORE

342 watching -

12:53

12:53

DeVory Darkins

15 hours ago $2.15 earnedKamala Intoxicated Video Message to Staff Shocks Internet

4.09K32 -

3:23:26

3:23:26

Pardon My Take

7 hours agoSUPER MEGA THANKSGIVING PREVIEW, KIRK COUSINS WANTS TO BE IN WICKED 2 + PFT/HANK RIVARLY CONTINUES

1.86K1 -

LIVE

LIVE

The Kevin Trudeau Show

3 hours agoWhat Women Do Wrong in Relationships (From a Man’s Perspective) | The Kevin Trudeau Show | Ep. 69

475 watching -

19:49

19:49

This Bahamian Gyal

13 hours agoFIRED after VENTING online about ELECTION results

2047 -

LIVE

LIVE

REVRNDX

3 hours agoYOUR NEW FAVORITE RUMBLE STREAMER

102 watching -

1:04:41

1:04:41

Russell Brand

2 hours agoIs This the End? Climate Emergencies, Kamala’s Chaos & Political Meltdowns EXPOSED! – SF502

73.4K127 -

LIVE

LIVE

The Charlie Kirk Show

2 hours agoThe Harris Team's Comical Post-Mortem + Trump the Peacemaker + AMA | Paxton, Greenwald | 11.27.24

6,585 watching