Premium Only Content

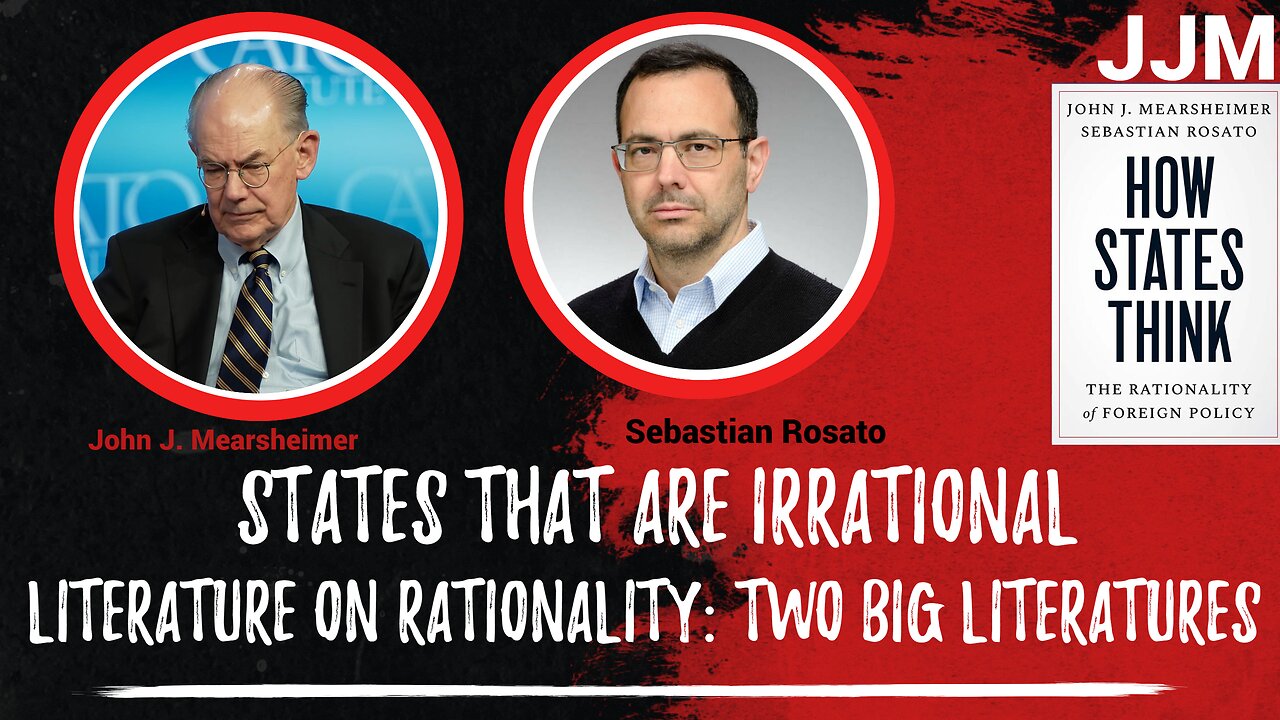

Sabastian Rosato and John Mearsheimer thought this was not the case decided to investigate the issue

Thank you very much, Justin.

Thank you to all of you for coming out to hear me talk today. Oh. Commonplace. The international relations literature today and in the public sphere for people to argue that states are irrational. That's not to say that everybody argues that, or everybody argues that states are irrational all of the time. But you hear that more and more, and again, you see it in the scholarly literature as well. Sabastian, Rosato and I thought this was not the case. Uh. First of all, if it is true, it has huge implications for international relations theory because almost all international relations theories are based on the rational actor assumption and if states. It's not rational. That's gonna cause all sorts of problems for those theories. Furthermore, if you're in the real world, you're in the White House, you're making foreign policy, and you assume that you're dealing with the world that's filled with states that are irrational. How do you make policy? It's almost impossible. So our basic intuition to start with, was that states. More rational and we decided we were gonna investigate the issue. What you have to understand this is a great importance is that to assess whether states are rational most of the time or irrational most of the time, you first of all have to have a clear definition of what rationality is. Markable how few people have a clear definition of what rationality is, but you can't assess whether states rational without clear definition of rationality. OK, and then the second thing you have to do if you could engage in the centerpieces Sebastian like did which you have to take that definition. You haven't rationality and run it up against your peripheral record of the historical record to see what the states were actually rational according to the definition that you have. So that's the enterprise that we were engaged in. Now when you look at the literature on rationality, there are two big literatures that are floating around out there. One is the rational choice literature, which is reflected in classical economics, and the other is the political psychology literature. Which is reflected in behavioral economics, which is quite fashionable today. But you see people in political science, people who study IR, saying there has been a revolution in political science or the study of IR. Those are people who fit the political psychology. Issue of the Rational Choice people, which has also been a popular way of doing international relations scholarship. Bodies of literature that are out there question you have to ask yourself is how do they define rationality? You need that baseline, right? It's quite clear both of them rely on expected utility maximization. So, what exactly is this? Let's just start with the rational choice. Rational choice literature says that states as act as if those words are very important, as if they were expected utility maximizers. Now what exactly is expected utility maximization? It's actually a magic. In many ways it's a brilliant formula. But it's magic formula that was invented by von Neumann and Orchestra back in the middle 1940s, and it says that rationality is employment of expected utility maximization. And expected utility maximization involves coming up with different policies that deal with the problem. It's got this thing called the Soviet Union out there at the end of World War 2, right? And you're not sure whether it's an aggressive state. Or it's a status quo power and you come up with policies for dealing. With the Soviet Union, right? And then when you marry the policies right with the problem, you come up with potential outcomes. And what you do is you rank order those outcomes. In other words, one policy choice would be to contain the Soviet Union. Another policy choice would be to leave Europe. And below the Europeans to contain the soap. The Soviet Union, and they're different policies and policies. Dealing with specific problems lead to different outcomes. So basically, you get 4 outcomes in this story. And what you do is you ran quarter those outcomes. And you then assign probabilities, or how likely it is that each one of those outcomes will happen. Does some math that's not terribly complicated and then you pick the outcome right? That gives you the greatest benefit or maximizes your utility. That's what's involved here. And the argument is in the international relations literature, among people who employ rational choice theory, that what states do is that they act as if they don't say. They act as they act as if they're expected utility maximizers. That's the definition of rationality. Through all sorts of problems with this. First of all, what does it mean to say that they act as if they're not saying that? If you look at how states behave, they act as expected. Utility maximizers? They're not saying that they actually use this formula to figure out. What the policy options are and then decide on the best policy option.

-

33:52

33:52

John J. Mearsheimer Official 2023

10 months agoIs Biden expanding the war Prof. John J. Mearsheimer

553 -

2:12:18

2:12:18

TheDozenPodcast

21 hours agoIslam vs Christianity: Bob of Speakers' Corner

45.6K12 -

14:36

14:36

The StoneZONE with Roger Stone

1 day agoRoger Stone Delivers Riveting Speech at Turning Point’s AMFEST 2024 | FULL SPEECH

48K13 -

18:59

18:59

Fit'n Fire

11 hours ago $4.23 earnedZenith ZF5 The Best MP5 Clone available

18K1 -

58:34

58:34

Rethinking the Dollar

20 hours agoTrump Faces 'Big Mess' Ahead | RTD News Update

20.5K5 -

5:35

5:35

Dermatologist Dr. Dustin Portela

20 hours ago $1.44 earnedUnboxing Neutrogena PR Box: Skincare Products and Surprises!

15.9K2 -

11:20

11:20

China Uncensored

19 hours agoCan the US Exploit a Rift Between China and Russia?

42.3K15 -

2:08:48

2:08:48

TheSaltyCracker

14 hours agoLefty Grifters Go MAGA ReeEEeE Stream 12-22-24

237K666 -

1:15:40

1:15:40

Man in America

17 hours agoThe DISTURBING Truth: How Seed Oils, the Vatican, and Procter & Gamble Are Connected w/ Dan Lyons

139K128 -

6:46:07

6:46:07

Rance's Gaming Corner

19 hours agoTime for some RUMBLE FPS!! Get in here.. w/Fragniac

170K4