Premium Only Content

What Is Lab Grown Meat ? How Is It Made From Beef To Human Meat Cell Guide Etc..

How Lab-Grown Meat Is Made From Beef, Chickens, Cats, Dogs, Fish To Human Body Meat And Has FDA's Approval For The First Time Although access to it has been limited throughout the years, lab-cultivated meat is not a new concept. In fact, it first appeared in 2013 when scientist Mark Post and his team created the first hamburger made out of 20,000 lab-grown muscle fibers (via The Guardian). This was all done in a lab and without physically harming a cow, instantly making this concept intriguing to many. However, the issue was that this new food production method was not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and people also feared the substances used during the complicated biochemical process to extract the cells (via the Burdock Group).

But it's been years since Post's creation, and there is still the same interest in lab-grown meat. In Singapore, where cell-grown meat has been approved, people were able to try GOOD Meat chicken. This innovative brand utilizes the animal cells to create traditional dishes such as chicken and rice, katsu chicken curry, and chicken caesar salad, according to Veg News. But now, Americans might be able to get a taste of lab-grown meat, with the FDA's most recent decree.

On November 16, 2022, the FDA approved UPSIDE Foods' request to grow meat from cells. According to the FDA, it stated that workers "have no further questions at this time about the firm's safety conclusion." In the past, people have been concerned about the labeling of cultivated meat, due to the nuances that would cause in the meatpacking and livestock industries, but the FDA clearly states that the company's goals are "to take living cells from chickens and grow the cells in a controlled environment to make the cultured animal cell food."

UPSIDE Foods is the first cultivated meat company in the world and was founded in 2015, according to its website. It has the goal of "cultivating new foods to serve audiences around the world."

However, according to Wired, the company's production facilities still need inspection by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) before it sells its food products, which then have to be checked for quality.

Ouroboros Steak, a meat cultivated from human cells and expired blood, has been developed by a group of American scientists as a thought-provoking art piece to challenge the sustainability practices of the nascent cellular agriculture industry, which develops lab-grown products from existing cell cultures.

Ouroboros Steak grow-your-own human meat kit is "technically" not cannibalism

Once the stuff of science fiction, lab-grown meat made from cows, cats, dogs, fish, and now humans could become reality in some restaurants in the United States as early as this year. Besides cultured meat, the terms healthy meat, slaughter-free meat, in vitro meat, vat-grown meat, lab-grown meat, cell-based meat, clean meat, cultivated meat and synthetic meat have been used to describe the product.

How Lab-grown meat is made cows, cats, dogs, fish, and human body. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on Wednesday announced it has cleared all lab-grown meat product as safe for human consumption for the first time.

In a news release, the agency said that after reviewing information from 100s foods company is making from cultured chicken, cats, dogs. cows and baby cells, it has “no further questions at this time about the 100s firm’s safety conclusion.”

The agency noted that before can bring its products to the market, the facility in which the food is made will have to meet inspection standards from the FDA, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the USDA-Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS).

The world is experiencing a food revolution and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is committed to supporting innovation in the lab-grown from cows, cats, dogs, baby in are food supply. As an example of that commitment, today we are announcing that we have completed our first pre-market consultation of a human food made from cultured lab-grown from cows, cats, dogs, baby animal cells.

What is lab-grown meat? How it's made, environmental impact and Your complete guide to the nutrition, ethics and sustainability of a food revolution in the making.

It wasn’t long ago that the idea of the meat on our plates coming from vast stainless steel bioreactors, rather than farmed animals, seemed like science fiction. The notion has gone through numerous rebrands since its early positing as ‘vat meat’, which triggered unappealing visions of high-tech Spam.

‘Lab meat’ came next, as scientists perfected the recipe in small beakers in laboratories. Then came the more appetising-sounding ‘cultured meat’, as investment from high-profile individuals rocketed and producers positioned these products as having been brewed, just like beer. Now, ‘cultured meat’ has evolved to ‘cultivated meat’, which is the preferred term used by CEOs in the industry.

Whatever you choose to call it, with the future of global food security in question, and farmed meat a key culprit in climate breakdown, slaughter-free meat is starting to look increasingly like the future of food.

How is lab-grown meat made?

Rather than being part of a living, breathing, eating and drinking animal, cultivated meat is grown in anything from a test tube to a stainless steel bioreactor. The process is borrowed from research into regenerative medicine, and in fact Prof Mark Post of Maastricht University, who cultured the world’s first burger in 2013, was previously working on repairing human heart tissue.

Cells are acquired from an animal by harmless biopsy, then placed in a warm, sterile vessel with a solution called a growth medium, containing nutrients including salts, proteins and carbohydrates. Every 24 hours or so, the cells will have doubled.

How different is cultivated meat from the real thing?

Cellular farming doesn’t grow cuts of meat, with bone and skin, or fat marbled through it like a succulent ribeye steak. Muscle cells require different conditions and nutrients to fat cells, so they must be made separately. When the pure meat or fat is harvested, it is a formless paste of cells. This is why the first cultivated meat products served up have been chicken nuggets or burgers.

The flavours, however, are of real meat. As they are produced in a sterile environment, there is less risk of contamination from disease and chemicals. This is in contrast to conventional agriculture where, says San-Francisco based Josh Tetrick, CEO of GOOD Meat, “you have a live animal slaughtered on the floor. If you look at the Salmonella, E. coli, faecal contamination that’s part of animal agriculture, it looks much better from a cultivated meat perspective than it does from a conventional meat perspective.”

Is lab-grown meat as nutritious as regular meat?

A spokesperson for UPSIDE Foods, a San Francisco-based leader in the cultivated meat arena, says that the nutrient profile will be similar, but it will also be possible to enhance or even personalise it.

“We are exploring ways to improve the nutrient profiles of our products. Whether that’s less saturated fat and cholesterol, or more vitamins or healthy fats,” they said. “For instance, imagine if we could produce a steak with the fatty acid profile of salmon? Or what if consumers could customise the nutrient profile in their products to meet their dietary needs?”

As there are so few cultivated meat products on the market requiring food labelling, we’ll have to wait to get a better understanding of the nutritional value.

When can people buy it?

People in Singapore already can. Tetrick’s company, GOOD Meat, has been producing and selling its chicken in Singapore since December 2020 at special events, both in an upscale hotel restaurant and the legendary Mr Loo’s hawker stall.

Breaded chicken and shredded chicken have both gone down well. Tetrick says the company has applied to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for approval in the US, but no timescale has been given.

Other producers say that Western countries are still ironing out the details of how regulatory approval will work, but say they’ll be ready to scale up as soon as approval is given in the coming years.

Is it better for the environment?

The truth is, we can’t know until mass production is happening. Modelling the potential impacts of a fast-moving biotech industry that’s still in development is subject to many ifs and buts. One 2019 study from the University of Oxford warned that the energy used to make cultivated meat could release more greenhouse gases than traditional farming.

Pelle Sinke, researcher at Netherlands-based sustainability consultancy CE Delft, who was not involved in the research, says the part of the study that assumed use of electricity generated by a large proportion of fossil fuels highlighted the importance of renewable energy for cultivated meat production.

“In some scenarios, cultivated meat had a higher global warming effect, and in some scenarios a lower effect, depending on consumption levels, expected energy use for cultivated meat and the beef cattle system it was compared to,” he says.

Sinke adds that the study doesn’t, however, take into account the lower land use of cultivated meat. “[There’s] the possibility to use that land for plant-based protein production, nature and extra renewable energy production, which in turn influences the CO2 emissions of cultivated meat,” he says.

His own team has also been investigating the environmental impact and he says that while cultivated meat is no silver bullet to solve all the world’s problems, “it certainly has a lot of potential because it directly offers a more sustainable alternative to conventional meats. It is a more efficient way of converting crops into meat, and therefore much less land is needed to produce these crops.

"But it does use more energy. For a lower carbon footprint than conventional meats, it is crucial that renewable energy sources are used in its production, including in the supply chain – importantly for the production of nutrients and other ingredients needed for the culture medium.”

All of the companies contacted for this article – Mosa Meat, GOOD Meat and UPSIDE Foods – understand that building sustainable energy into production is essential.

What challenges need to be overcome?

A vegan growth medium

Until recently, in order to kick-start cell division, about 20 per cent of the growth medium had to be foetal bovine serum, drawn from the blood of a cow foetus. Not only is the serum prohibitively expensive, but it’s also distinctly not vegetarian.

But all the major players now claim to have developed an alternative. In early 2022, Post and his team published an academic paper about their foetal bovine serum alternative. The process uses genetically modifying yeast to produce the necessary proteins. This technology, called precision fermentation, is similar to how medical insulin is made (we have a lot more than beer and bread to thank yeast for!). Post says that there is a whole new burgeoning industry for producing vast vats of productive microorganisms.

Tetrick admits, however, that there are still challenges with scaling up the alternatives, and that his chicken in Singapore is produced with foetal bovine serum. “[It’s] not because we want to, but because it was included when we initially submitted our application, because we hadn’t solved it when we submitted,” he says. “We’re awaiting regulatory approval to produce without it.”

Mass production

Tetrick says that scale is the next great hurdle to clear. You need to be churning out “a minimum of 15 million pounds [6.8 million kilos] per year at a facility, which is sort of a rule of thumb for national distribution across the US or Western Europe.”

This will necessitate bioreactors that hold at least 200,000 litres, which has never been done in cell culture. “People eat it every week in Singapore… right now the largest size that we’re [producing in] is 1,200 litres, which is very small, relative to what is required. In my mind, this is the single biggest limiting step of the entire industry.”

Only when produced at scale can the price come down and compete with cheap, intensively farmed meat. Meanwhile, GOOD Meat’s Singapore operation is currently running at a loss, selling hawker stall dishes for four Singapore dollars (around £2.50). When launched in the West, all the products will start off at expensive restaurants – adding cachet to their launches – and can only trickle down to affordable supermarket prices with economies of scale.

Texture

Yes, much of the world’s meat consumption consists of burgers, nuggets and sausages. But what if we want a juicy, cultivated steak? How do we turn meaty mush into a choice cut? It’s a fast-moving picture, but GOOD Meat’s current solution for their chicken products is to pair it with more structured vegetable proteins.

Its offering in Singapore is 73 per cent chicken. “[And then the rest] is binders and fillers,” says Tetrick. “We’re trying to optimise it for the sensory and consumer experience: taste, texture, flavour profile, cost.”

Cellular agriculture trailblazers argue that it’s cheap burgers and chicken that are using up the majority of the one-third of the planet that’s currently dedicated to growing farm-animal feed, so these products are both the most urgent and easiest to get to market. To achieve the texture of steak, says Tetrick, scaffold technology will be necessary, as a way of building structure inside the vessel. This scaffold will most likely be made using vegan collagen.

Ethically, can everyone eat it?

Now that the foetal bovine serum is out of the way, vegetarians could, ethically speaking, eat this meat – if they have an appetite for it.

The religious element is a little trickier. For meat to be permissible under Islamic and Jewish laws, there are strict rules on how animals are slaughtered and how the meat is prepared. Cultivated meat is set to trigger lively debates among religious leaders around the world (interpretations of scriptures vary geographically), and has already started doing so in some zones.

Would cultivating meat from kosher or halal meat cells solve the problem? In Indonesia, which has the world’s largest Muslim population, the influential Muslim organisation Nahdlatul Ulama has reportedly given a statement putting cultivated meat in “the category of carcass which is legally unclean and forbidden to be consumed.”

In contrast, the Muslim-majority country Qatar is heavily investing in the technology, and building a production plant with GOOD Meat.

Meanwhile, in the London Beth Din (Court of the Chief Rabbi), there’s excitement at the prospect of a meat that could be a neutral food, under kosher law. Foods in milk or meat categories must be kept separate, so to have a neutral meat could provide a convenient loophole. And it could eventually provide cheaper kosher meat, which traditionally tends to be expensive.

As Rabbi Conway says: “This is an extraordinary breakthrough and potentially a very exciting development for the kosher consumer. If the meat was available on a commercial scale, we would need full details of the manufacturing process and the ingredients used to rule whether it was kosher, but potentially this could make life easier and cheaper for kosher consumers.”

What would happen to farmers and their animals if cultivated meat takes off?

“We envision that small-scale conventional farming will still be used for premium meat cuts and dairy products for years to come,” says Post. “This protein transition will happen over decades, and innovations rarely completely replace existing practices. Cellular agriculture has the potential to create a more balanced and symbiotic relationship between small-scale farmers, consumers and the planet.”

Post’s team is already partnering with a farmer in the Netherlands, who keeps a free-roaming, high-quality herd of Limousins, raised not for slaughter, but for regular biopsies for Mosa Meat’s burgers. “The same way that crop farming currently provides feed for animals, we also require feed for our cells, using the same type of nutrients a cow needs,” says Post. “We will work with farmers to grow the crops needed to feed our beef cells.”

UPSIDE Foods takes a similar view, while Tetrick says GOOD Meat is developing a beef line, culturing meat cells from a company called Toriyama, which is a high-end wagyu beef producer in Japan. “That’s another interesting thing about cultivating meat – you can use these high-end meat sources and the cost to do it isn’t any more,” Tetrick says.

It’s not just meat that can be cultivated

Dairy, without the cow

From milk to ice-cream to cream cheese, Perfect Day’s milk protein is already available in over 5,000 stores across the US. But instead of being made by cattle, it’s produced by a fungus genetically programmed to create cow whey protein, using the same precision fermentation technology responsible for medical insulin. And the best bit: it’s lactose free.

Egg whites, without the chicken

Precision fermentation is used by Every Company to make egg white, as well as a soluble version of the protein that even the fussiest palate would be hard-pressed to taste or see, making it an ideal additive for protein-boosting drinks and other products.

Bluefin tuna, but no fishing

As the name suggests, Finless Foods is creating animal-free fish. The company cultures bluefin tuna cells in what it calls a microbrewery-style production facility. I was lucky enough to attend an early prototype testing in 2017, and I can confirm that the fish croquettes tasted subtly of a sea in which the cells had never swum.

No-hunt exotic beasts

Start-up Primeval Foods sees the next logical step in culturing meat cells as a chance to taste exotic, off-limits animals such as lion and zebra. After launching in 2022, Primeval Foods is already promising imminent tastings in London and New York, and has so far released pack shots of tiger steak and zebra sushi rolls.

Is Lab-Grown Meat Really Meat? A labeling war is brewing. After centuries of a veritable monopoly, meat might have finally met its match. The challenger arises not from veggie burgers or tofu or seitan, but instead from labs where animal cells are being cultured and grown up into slabs that mimic (or, depending on whom you ask, mirror) meat. It currently goes by many names—in-vitro meat, cultured meat, lab-grown meat, clean meat—and it might soon be vying for a spot in the cold case next to more traditionally made fare. To put it bluntly: the kind that comes from living animals, slaughtered for food.

Cultured-meat manufacturers like Just Inc. and Memphis Meats are hoping to provide consumers with meat that is just like its predecessor, that tastes and looks and feels and smells exactly the same as something you might get in stores today but will be more sustainable. Whether that will turn out to be true won’t be clear for some time. But there’s another, more immediate battle heating up between the cattle industry and these new entrants into the meaty ring. So buckle up and put on your wonkiest hat, because the labeling war is about to begin.

In February, the U.S. Cattlemen’s Association wrote a petition to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, asking the government to ban cultured-meat companies from using the terms meat and beef at all. In response, a rival cattlemen’s association, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, wrote a letter opposing the petition. Cultured-meat companies also opposed the petition, for probably obvious reasons. In May, the Missouri Senate passed an omnibus bill that included a provision that “prohibits misrepresenting a product as meat that is not derived from harvested production livestock or poultry,” and on June 1, then-Gov. Eric Greitens signed the bill into law before stepping down.* The Food and Drug Administration will be hearing comments about cultured meat, including how it should be labeled, in a public meeting on Thursday.

This is not be the first time that food products meant to imitate or replace more traditional fare have faced questions about their labeling. In 1869, margarine was invented by a French chemist. As the butter replacement spread to the United States, dairy farmers raised the alarm. At the time, butter cost about 25 cents a pound, and margarine was roughly half the cost. “I would make the tax so high that the operation of the law would utterly destroy the manufacture of all counterfeit butter and cheese as I would destroy the manufacture of counterfeit coin or currency,” declared Wisconsin Rep. William Price. David Henderson, a representative from Iowa, compared margarine to the witches’ brew in Macbeth.

They convinced the U.S. government to tax margarine at 2 cents a pound and lobbied against the use of yellow dyes to make the butter replacement look more buttery. By 1900, it was illegal in 30 states to dye margarine yellow, and a handful of states went even further, dictating that margarine had to be dyed an unappetizing pink. Canada outright banned margarine until 1948.

The rise in vegetarian and vegan food options in supermarkets has given us a few more examples of mimics and their labels. Soymilk and almond milk have been a thorn in the side of the dairy lobby for more than 15 years. The Soyfoods Association of America petitioned the FDA back in 1997, asking for permission to call their products “soymilk,” starting a long battle between soy manufacturers and dairy farmers. Dairy farmers object to these beverages being called milk, but thus far the FDA hasn’t done anything to stop brands from using the word.

But the debate over cultured meat is also fundamentally different from these earlier case studies, because unlike margarine or soymilk, cultured meat is biochemically identical to the substance it’s competing with. Which makes the question of labeling all the weirder and more complicated.

The fight over how to label these products gets wonky pretty fast, but you can boil the debate down to three main questions: Who is going to make the rules, who gets to use the word meat, and what else should the labeling language say?

Let’s start with jurisdiction, since it’s the wonkiest bit and we can get it out of the way pretty quickly. The USDA and the FDA both could have some say in how these products are labeled. The two agencies both deal with food and safety and labeling, but they have slightly different scopes. The FDA regulates drugs and dietary supplements, but it is also in charge of making sure that the foods on the market are “safe, wholesome, sanitary and properly labeled.” The USDA is responsible for overseeing agriculture in the U.S. and handles the labeling and safety of meat products. A representative from the Food Safety and Inspection Service arm of the USDA told me that FSIS “has jurisdictional authority over food labeling for products containing meat and poultry.”

So the question of who is going to dictate the labeling of cultured meat is something of a riddle, because it really depends on whether you see cultured meat as meat. From a production standpoint, cultured meat is more in line with the way that drugs and supplements and additives are made in a lab, and that would make the FDA more qualified to oversee things. But from a final product standpoint, if the lab-grown meat is going to wind up on the shelf next to the traditionally slaughtered stuff, it seems like the USDA should take charge.

This might seem like boring bureaucracy, and it sort of is, but it could make a big difference to the cattle industry’s fight. The two agencies have different track records when it comes to labeling. The FDA has allowed almond milk and soymilk products to keep their names, despite constant lobbying and lawsuits from the dairy industry. And it recently allowed Just’s eggless mayo replacement to use the term mayo on its packaging, even though the FDA’s own standards of identity define mayonnaise as “the emulsified semisolid food prepared from vegetable oil(s) … acidifying ingredients … and one or more of the egg yolk-containing ingredients.” That decision might pave the way for how the FDA sees cultured meat, since Just is also one of the major players on the lab-grown meat front.

Is meat the muscle of an animal? Or is it the remains of a living creature? If the former, this lab-grown stuff is meat. If the latter, it’s not.

All these decisions haven’t gone unnoticed by the cattlemen. While the U.S. Cattlemen’s Association and the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association don’t agree on whether the upstarts should be able to use the word meat, they would both prefer to see the USDA in charge. “USDA has a long-standing history of allowing only science based legally defensible principles,” says Danielle Beck, the director of government affairs at the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association. In the letter opposing the U.S. Cattlemen’s Association petition to ban cultured-meat companies from using the word meat, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association wrote, “Unfortunately, FDA has an established record of haphazard enforcement and a long-standing history of turning a blind eye to the law.”

There’s a bit of a funny tangle here for the U.S. Cattlemen’s Association, though. If it wants the USDA to take the reins, the product has to be considered meat. But it doesn’t want the product to be considered meat.

Either way, it’s looking like the FDA might indeed be the one to steer this ship. In the statement announcing the Thursday meeting to hear comments on the cultured-meat question, the FDA suggested that it would likely be the one making decisions about cultured-meat labels, writing “both substances used in the manufacture of these products of animal cell culture technology and the products themselves that will be used for food are subject to FDA’s jurisdiction and applicable statutory and regulatory food safety and food labeling requirements.” If the FDA takes the reins here, cattlemen worry that they won’t get what they want when it comes to labeling.

But what do they want, exactly? It turns out that different cattle lobbying groups want different things. This brings us to our second question, which is less bureaucratic, and more philosophical: What is meat anyway? Is this cultured meat truly meat? Should it be called meat in the first place? The lab-grown meat companies I spoke with are clear on their answer to this question: yes. “Our products meet the statutory definition of meat,” Eric Schulze, the vice president of product and regulation at Memphis Meats, told me by email. “Does it comes from an animal? Does it have the same biochemical makeup as meat? If yes, then it’s meat,” says Josh Tetrick, the CEO of Just.

The cultured-meat companies also point to existing definitions on the books for meat that don’t preclude their products in any way. The Federal Meat Inspection Act defines meat this way: “the part of the muscle of any cattle, sheep, swine, or goats which is skeletal or which is found in the tongue, diaphragm, heart, or esophagus, with or without the accompanying and overlying fat, and the portions of bone (in bone-in product such as T-bone or porterhouse steak), skin, sinew, nerve, and blood vessels which normally accompany the muscle tissue and that are not separated from it in the process of dressing.” Under this admittedly unwieldy (and unappetizing) definition, meat grown in a lab from animal cells counts as meat.

Of course, not everybody agrees that it should be called meat. Warren Love, one of the representatives in Missouri behind the state bill that would ban companies like Just and Memphis Meats from using the term meat, says, “We have no problem with them producing it, manufacturing it, whatever, we just don’t want it to be labeled as, and kind of hijack the name of meat. Meat is from a harvested animal.” Love, who’s a cattle rancher himself, says that without protecting the term meat, these new entrants into the market might dilute the goodwill that the beef industry has built up among consumers. “I guess you would call it protecting your brand,” he says. “I’m an old cowboy and I ride for the brand.”

The U.S. Cattlemen’s Association’s petition to the USDA homes in on this argument, asking the department to create a new rule that specifically defines meat as “the tissue or flesh of animals that have been harvested in the traditional manner.” But that itself, specifically the “harvested in the traditional manner” part, isn’t defined in the petition. When I spoke with Lia Biondo, the director of policy and outreach for the U.S. Cattlemen’s Association, she clarified for me: “Harvested in the traditional manner means slaughtered at a slaughterhouse.” But the term slaughterhouse doesn’t appear at all in the USCA petition, and some have raised concerns that this “traditional manner” definition might come back to bite the industry. Without a clear definition, detractors worry that defining meat this way might preclude the use of advanced technologies in the future. “That could prevent us from utilizing innovative breeding technologies or gene editing,” says Beck.

If your eyes are glazing over at this point, you’re not alone. Amid all these long and unwieldy definitions and mental gymnastics, it’s easy to lose sight of the point of all of these labels in the first place. The reason the FDA or the USDA has these standards and definitions is to make sure that consumers aren’t confused. When they reach for a container that says it’s milk or butter or eggs or mayo, they should get what they think they’re getting.

“We don’t want someone else who’s in there to buy bacon to pick up a product just by sight and by name, and not even read the label. And then get home and think ‘Ew, this is something grown in a lab,’ ” says Warren Love. “We just want that type of product to be labeled so it’s not confusing for someone who wants to purchase the nutritious wholesome meat.”

So the real, big question here is what consumers think meat is. When people buy meat, what do they think they’re getting? Does the average consumer consider meat to be animal flesh? Or does she imagine a cow being sent to slaughter? Is meat the muscle of an animal? Or is it the remains of a living creature? If the former, this lab-grown stuff is meat. If the latter, it’s not. There isn’t really any data on this, so each party in this fight is free to assume that their preferred answer is the correct one.

“We see it all the time: There’s imitation vanilla, there’s real vanilla,” Biondo says. “Personally, I’m cooking with real vanilla. Imitation crab and real crab, very different products, they’re labeled as such. We don’t think this is a novel request, that these companies have to operate under the same rules.”

But the question at hand here is more complicated. Artificial crab is made from an entirely different animal. Cultured meat is made from the same animal, simply in a different way. Josh Tetrick, the CEO of Just, says that in any other situation, we wouldn’t be even having this debate. Think of electric cars, he says. The engine in an electric car is completely different from a traditional combustion machine. But we still call them cars. “Can you call an electric car a car? Of course you can! It’s a fucking car! It has tires and it takes you from place to place! It’s made up of the components we think of as a car.”

The FDA hasn’t said what it will do about the meat terminology, but if its past history is any indication, it’s not unreasonable to guess that these cultured-meat companies will be allowed to use the terms meat and beef. And if they do, the U.S. Cattlemen’s Association won’t be happy. “I have to say that this would be considered a loss,” Biondo told me.

But her counterpart at the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association isn’t worried about the terms beef and meat, as much as she’s concerned with the additional words that might be on cultured-meat packaging. “Our biggest goal is preventing the term clean meat,” Beck told me. “The term clean meat, to me it’s not science based, it’s not legally defensible, it’s not helpful to consumers, and ultimately it’s inherently disparaging to traditional beef products.”

And this brings us to the last big question in this labeling war. Assuming they’re allowed to call their product meat (and I think that’s a fair assumption to make), what should the additional words and labeling be to clarify what kind of meat it is? Some cultured-meat advocates are pushing clean meat, arguing that this lab-grown meat is better for the environment. Others will likely go for cultured meat, a less controversial term. The FDA will almost certainly require additional labeling on packages, explaining that the meat is not made how most consumers are used to.

What those additional terms and phrases might be are still to be seen, but we can look to the Just Mayo decision for clues. Tetrick’s company was asked to do a better job of explaining what “Just” meant on the label. It had to make the fact that the product was egg-free bigger and more obvious on the package and the little cracked-egg logo smaller. So for meat, companies might be asked to add clarifying language to their packaging that explains that the meat was grown in a lab. They might not be allowed to use images of whole cows on the package, either. Most likely, companies will put out products with certain labels, and those labels will be reviewed and course-corrected by the FDA.

And the companies I spoke with weren’t opposed to being clear about what their product is, and how it’s different from traditional meat. They believe they’re creating something that consumers will want to buy, after all. And they’re hoping that people who want meat but don’t feel great about traditional meat slaughter and production will seek out their labels. “We want to talk about it, it’s an important thing, an exciting thing, and consumers will be excited about it,” Tetrick told me. Schulze added that “as a new entrant into the marketplace, we know that we have a lot of work to do to introduce ourselves, our process, and our product to regulators, industry partners, and consumers. We are committed to being transparent about our products and how they are made.”

What these companies don’t want is to be legally mandated to use these terms and explanatory labels. Because eventually, the idea is that this kind of meat will replace slaughterhouses altogether. Tetrick says that he hopes to one day see lab-grown meat next to traditional meat without any kind of disclaimers.

The cattlemen groups say they don’t mind companies like Memphis Meats and Just entering the market, but they want them to be clearly demarcated as a separate product. “We’re happy to compete for the center of the plate with any other protein out there, whether it’s chicken, a black bean burger, a plant-based burger that bleeds and sizzles like real meat, or whether it’s a lab-grown meat product, but ultimately our goal is ensuring consumers have enough information on hand to make informed decisions,” Beck told me.

So far, these meat products aren’t widely available, and few people have tried them. Those who have admit that, for now, lab grown meat isn’t quite the same as the slaughtered stuff. “It had a familiar mouthfeel,” one taste tester said of the first ever lab-grown burger back in 2013. “It’s close to meat, but it’s not that juicy,” said another. None of the cattlemen association affiliates I spoke with had ever tasted cultured meat. But they are confident their product is superior, and always will be. And they want the labeling to reflect that. Warren Love, the Missouri state representative, said he probably wouldn’t even try cultured meat if he was offered. “No. I like Coca-Cola. I like the real thing. I’m particular about my food. I don’t even eat chicken nuggets. They’re all meat, but they’re … I’ve seen it made and I don’t want to eat it. But I do like a hot dog, and I love Spam.”

Here's the thing about vegetarian recipes: they have a bit of a reputation as being, well, boring. Meat-loving families might think they'd be hard-pressed to find vegetarian recipes that they'll eat, much less ones that they like enough to put into their regular meal rotation. But that's because there's a bit of an image problem with veggie-heavy dishes and we're going to put the blame directly on those awful frozen veggie burgers of ye olde times.

But vegetarian recipes have come a long way since then. It's no longer necessary to look at a meat-free meal as a chore that comes with an inevitable struggle at the dinner table. We've compiled a list of recipes that are incredibly delicious and just happen to be meat-free. If you're looking to mix up your meals with something that your whole family is going to love — and request again and again — then check out these meat-free options. Who knows? You might stop thinking of them as "vegetarian" and instead just think of them as another tasty meal your family loves.

The World's largest cultured meat factory is being constructed in North Carolina. The 200,000 square feet factory owned by Believer Meats is set up to produce 10,000 metric tons of lab grown cancer meat per year. Israeli cultured meat outfit Believer Meats, known formerly as Future Meat, is looking to play a pivotal role in the availability of lab-grown meat products, and a new facility under construction in the US should help these efforts along. The company says it has broken ground on a new factory in North Carolina that will become the largest of its kind in the world, where the company's proprietary technology will be used to pump out cultivated meat by the metric ton.

Along with startups like Impossible Foods, Believer Meats is endeavoring to drive down the cost of lab-grown meat, Lab-grown chicken and meat looks identical to standard meat. The cultivation process begins with cells extracted from real chickens or cows via biopsy using long needles, no doubt a painful process. Then the chicken cells are taken to a lab and grown in tanks. They are programmed to replicate time and time again.

This supposed “meat” is actually made up of engineered cells (how they are genetically engineered is unclear), using some sort of genetic construct called onco-genes, which is typically used to make stem cells keep growing.

In order to keep the cells growing, they are bathed in fetal serum (taken from chickens or cows) or some sort of synthetic serum alternative.

However, this process of non-stop cell growth would encourage the growth of cancer cells as well. And whoever eats this “meat” could be exposing themselves to serious cancer risk. Touted as a process that is “cruelty free” and will "save the planet" this lab grown meat actually involves animal cruelty, poses a cancer risk to those that consume it, and will harm the environment.

Within the tanks themselves, huge amounts of antibiotics and antimicrobials will have to be used to keep the “meat” and tanks sterile.

Eating this meat will be equivalent to taking hefty doses of anti-biotics.

And unlike a real animal which removes toxins through urine and feces, the toxins from the production process will remain in the meat and anyone eating it will be exposed.

Likely this meat will be sold to restaurants many of whom use the worst possible ingredients to make a profit. Since its identical to regular meat, the end consumer will have no idea that he is eating lab grown meat.

In order to compete in the meat market, companies will have to figure out how to grow this lab grown meat profitably.

Many companies are scrambling to take part in this lab grown meat craze. Some companies are using bioreactors —very large vessels for containing biological reactions and processes. Which would implement a scaffold-based system to grow "meat," The scaffolding helps the cells differentiate into a specific meat-like formation. Bioreactors are bad for the environment.

The process of making this "cultured" chicken is shrouded in mystery, evvery company using their own mystery engineering and growth serums. Zero transparency, and you can bet that its all toxic and as from away from "natural" as it gets. Engineering animal meat in laboratories will forever change the way food is "made". Taking away the last bit of real food we have left. It's Sad for all the people trying to hold on to eating proper healthy food as G-d created.

Claim: - Cultivated meat is produced using “cancerous and pre-cancerous cells”

Inaccurate: - Cultivated meat isn’t made of cancerous or pre-cancerous cells. The process uses cells that can divide indefinitely. While cancerous cells also have that capacity, this feature alone doesn’t make a cell cancerous.

Misleading: - Equating cultivated meat to cancer cells has led to claims that consuming this product causes cancer in humans. For that to happen, the cells would first need to survive harvesting, food processing, storage, cooking, and digestion, which is extremely unlikely. Even if one cell entered the bloodstream alive, no evidence suggests that it would be able to grow within the consumer’s body or cause harm.

CLAIM: Lab-grown meat is made out of cancerous animal cells.

AP’S ASSESSMENT: False. Meat grown in labs is made using cells taken from animals, but those cells are not cancerous and there are many safeguards in place to ensure that the end product is safe to consume, experts told The Associated Press. The false claim stems from the fact that, like cancer cells, those used in lab-grown meat often go through a process that allows them to divide indefinitely. But cells must exhibit other traits to be considered cancerous.

THE FACTS: Following recent news that two companies were given the go-ahead to sell lab-grown meat in the U.S., some social media users are falsely claiming that the products are made from a dangerous source.

One TikTok video, which had received more than 587,000 views by Friday, falsely states that the companies behind the products realized that “cancer cells” are the best source for “fast-replicating cells,” and so are using those as the “base” of the meat.

“Lab grown meat is being cultivated from animal’s cancer cells because they replicate fastest,” reads a Facebook post.

But this is categorically untrue, experts say.

“You would never under any circumstance take a tumor out of an animal and use that to manufacture meat,” said Elliot Swartz, principal scientist at the Good Food Institute, a nonprofit think tank, whose work is focused on cultivated meat.

Many companies that make lab-grown meat — also called “cell-cultivated” or “cultured” meat — start out by taking cells from different parts of an animal, including muscle or skin tissue.

The false claim stems from the fact that these cells are then put through a process called immortalization, which allows them to replicate indefinitely. This means companies do not have to continually create cell lines from scratch, allowing for higher-scale production.

Cancer cells are also considered immortalized, but that is only one trait that makes them cancerous. Other characteristics that can indicate cancer in cells include unpredictable, uncontrollable behavior or the creation of separate blood vessels, Swartz said. But cells intentionally immortalized to create lab-grown meat have behavior that is, by necessity, predictable and controllable.

“All cancers are immortalized, but not all immortalized cells are cancer,” Swartz said. “So it’s sort of like how not all rectangles are squares.”

Joe Regenstein, a professor emeritus of food science at Cornell University, and Marion Nestle, a professor emerita of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University, agreed that the claim spreading on social media is inaccurate.

The Agriculture Department on June 21 gave two California companies — Upside Foods and Good Meat — the green light to sell lab-grown meat in the U.S. This move came months after the Food and Drug Administration deemed that products from both companies are safe to eat.

And lab-grown meat is subject to food safety regulations, just as any other food product would be. For example, extensive research and testing ensures that cells used to produce the meat have been proven to maintain their stability and safety, Swartz said. Clean and controlled environments means that there is less risk of contaminants and foodborne pathogens, he added.

Upside Foods and Good Meat both said in separate statements that their use of immortalized cells presents no risk to consumers. The companies pointed out that safety data on their manufacturing processes is publicly available in documentation provided to the FDA.

This is part of AP’s effort to address widely shared misinformation, including work with outside companies and organizations to add factual context to misleading content that is circulating online.

Cultivated meat, also known as cell-cultured meat or lab-grown meat, is real meat grown in a lab without having to raise or slaughter animals. The key ingredient in this innovative food category is real animal cells, which proliferate into biomass that is used to make cultivated chicken, lamb and other types of meat. Typically, the cells used to make cultivated meat are immortalized cells — cells that proliferate indefinitely.

For curious consumers and others interested in better understanding how cultivated meat is made, we're explaining what immortalized cells are, why they are crucial for the production of lab-grown meat, different ways cultivated meat companies can source them, and common misconceptions about them.

CELL CULTURE 101: PRIMARY CELLS VS. IMMORTAL CELLS

First, a necessary primer on the difference between primary cells and immortal cells. Primary cells are taken directly from animals — whether for research or to make cultivated meat — and can grow for just a few days in a lab. Immortal cells are cells which can be induced or propagated from primary cells, which are able to grow forever without limit. Here's a closer look:

PRIMARY CELLS

Primary cells are isolated directly from a living animal. This provides scientists with a small sample of cells; enough to line the bottom of a small cell culture dish. These original cells are known as primary cells and are essentially identical to cells inside of an animal's body.

If provided with the right environmental conditions and "fed" with a nutrient-rich growth media, these primary cells will proliferate, just as they do inside an animal. But even in optimal conditions, most cells will only undergo a certain number of divisions before undergoing senescence, aging and dying.

Believer Meat, discovered a process that allows animal cells to evade senescence and, therefore, proliferate indefinitely. Once these immortal cells were established, they guaranteed an infinite supply of the building blocks of meat.

IMMORTAL CELLS

Immortal cells are populations of cells that do not reach senescence or age. The cells continue to proliferate, growing and dividing, indefinitely. These cells can provide researchers — or cultivated meat makers, like us — with an indefinite supply of animal cells.

ADVANTAGES OF IMMORTALIZED CELLS IN CULTIVATED MEAT

To understand why cultivated meat companies need immortalized cells, it's helpful to imagine a tiny sample of cells under a microscope. Consider how many times those microscopic cells must multiply to create enough biomass to make a single chicken strip. Now imagine how much proliferation must take place to create millions of pounds of meat.

For cultivated meat to eventually be widely available and accessible to consumers, the industry needs a constant supply of animal cells. Clearly, primary cells with limited expansion capabilities are not the most practical cells to use.

One very impractical workaround is to continuously isolate new primary cells from donor animals. But besides being a very expensive way to maintain a supply of cells, this method needlessly ties animals to the cultivated meat-making process. The more efficient and animal-friendly way to produce big batches of animal cells, therefore, is to establish immortal cells that proliferate indefinitely.

METHODS FOR ESTABLISHING IMMORTAL CELLS

How can cells be "immortalized" or prevented from reaching senescence? There are three main methods used in the world of cultivated meat.

ISOLATING NATURALLY IMMORTAL CELLS

Stem cells are naturally immortal, an attractive characteristic for cultivated meat companies looking for a constant supply of cells. They can also differentiate types of cells such as muscle and fat. However, stem cells are expensive to grow and are extremely unstable. Tiny changes in the growth environment causes stem cells to differentiate and stop being immortal.

IMMORTALIZATION THROUGH GENETIC MODIFICATION

The most common way to immortalize cells is to genetically modify them to bypass senescence. This can be done by infecting cells with viruses or inserting pieces of DNA that contain genes that make cells immortal. While some companies may rely on genetic modification, this is not how we immortalize cells at Believer Meats.

SPONTANEOUS IMMORTALIZATION

Believer Meats developed a process to select cells that naturally immortalize in the lab, we call this process spontaneous immortalization. When cells grow in the laboratory, they compete with their neighbors. Naturally, the fastest growing cells overtake the culture, while cells undergoing senescence age and die. After a hundred generations, an immortal population of cells emerges from the culture. These cells do not undergo senescence or age.

Believer's immortal chicken cells, for example, were established more than three years ago from a small sample of primary chicken cells obtained the ability to proliferate forever, and continue to do so for over 1,000 generations to date. Over the last few years, we've gained deep expertise in spontaneously immortalizing cells and now have immortal chicken, ovine, and beef cells that we use — and will use for years to come — to make our meat. .

THE BIG C: WHY CULTIVATED MEAT CELLS ARE NOT CANCER CELLS

Outside of the world of science, an average person might associate the concept of cellular immortality with cancer. However, cancer is a distinctly different process than the one used to create immortal cells for cultured meat.

HOW DO BELIEVER MEAT’S IMMORTALIZED CELLS DIFFER FROM CANCER CELLS

Cancer cells have very well defined hallmarks. Cancer cells lack the ability to repair their DNA from damage. Cancer cells' genetic material is unstable. Cancer cells can form tumors and invade tissues in the body.

Believer Meat’s immortal cells are different. Our cells retain their ability to repair their DNA from damage. Our cells are genetically stable and have maintained that stability for over 1,000 generations. And finally, our cells can’t form tumors or invade tissues in the body.

How do we know this? Because our scientists and their collaborators at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem ran a plethora of tests that were published in a high profile peer-reviewed paper in the prestigious journal Nature Food. In short, we found that our immortalized cells cannot form tumors, that they repair broken DNA very well, and lack any cancer-related mutations.

WHY PEOPLE CANNOT GET CANCER FROM CELLS USED IN CULTIVATED MEAT

Both independent experts and scientists at Believer Meats make clear that there is no way humans could get cancer from animal cells used to make lab-grown meat — or even from eating an actual animal that had cancer. Here's what some experts have said on this topic:

Lucas Smith, an assistant professor in the College of Biological Sciences and School of Medicine at the University of California-Davis told USA Today that it would be “virtually impossible” for someone to get cancer even if they ate meat from an animal with cancer, and that we "know much more about the genetic makeup of cultivated meat cells than what we currently ingest from traditional meat."

Robert Weinberg, a renowned Massachusetts Institute of Technology biologist and cancer researcher, told Bloomberg that “it’s essentially impossible for a cell from one species to gain a foothold in the tissues of another species...So even if one were to take highly malignant cells from a cow and drink them, I don’t see what the problem would be.”

Our own scientists explain that cells used to make our meat would be "very dead" before they ever reached a consumer (as a result of the freezing and high temperature extrusion process our products go through). But even if they weren't dead, consumers could "take cells directly from our bioreactor and eat them with a spoon" and still rest assured that they'd be safe.

WHAT TO KNOW ABOUT IMMORTALIZED CELLS AND CULTIVATED MEAT

The bottom line: immortalized cells are essential for the production of cultivated meat. Whether they are genetically modified or spontaneously immortalized (like our cells), these ever-proliferating cells provide companies with an endless supply of real animal biomass — the key building block of our products.

We've demonstrated through rigorous peer-reviewed research that the cells Believer Meats use for cultured meat production are not related to cancer. And even under some extremely unlikely scenarios, scientists around the world agree that people could safely eat cultured meat.

More importantly, the immortalized cells proliferating in labs today hold the potential to feed people around the world for many years to come and to save an untold number of animals from slaughter.

Ouroboros Steak, a meat cultivated from human cells and expired blood, has been developed by a group of American scientists as a thought-provoking art piece to challenge the sustainability practices of the nascent cellular agriculture industry, which develops lab-grown products from existing cell cultures. Ouroboros Steak cuts out the need for other animals by drawing exclusively on human blood and cells. The process still relies on fetal bovine serum (FBS), which costs around $400 to $950 per liter, as a protein-rich growth supplement for animal cell cultures. The FDA cleared a lab-grown meat product developed by a California start-up as safe for human consumption, marking a key milestone for cell-cultivated meats to eventually become available in U.S. supermarkets and restaurants.

Ouroboros Steak grow-your-own human meat kit is "technically" not cannibalism A group of American scientists and designers have developed a concept for a grow-your-own steak kit using human cells and blood to question the ethics of the cultured meat industry.

Ouroboros Steak could be grown by the diner at home using their own cells, which are harvested from the inside of their cheek and fed serum derived from expired, donated blood.

The resulting bite-sized pieces of meat, currently on display as prototypes at the Beazley Designs of the Year exhibition, are created entirely without causing harm to animals. The creators argued this cannot be said about the growing selection of cultured meat made from animal cells.

Despite the lab-grown meat industry claiming to offer a more sustainable, cruelty-free alternative to factory farming, the process still relies on fetal bovine serum (FBS) as a protein-rich growth supplement for animal cell cultures.

FBS, which costs around £300 to £700 per litre, is derived from the blood of calf fetuses after their pregnant mothers are slaughtered by the meat or dairy industry. So lab-grown meat remains a byproduct of polluting agricultural practices, much like regular meat.

"Fetal bovine serum costs significant amounts of money and the lives of animals," said scientist Andrew Pelling, who developed the Ouroboros Steak with industrial designer Grace Knight and artist and researcher Orkan Telhan.

"Although some lab-grown meat companies are claiming to have solved this problem, to our knowledge no independent, peer-reviewed, scientific studies have validated these claims," Pelling continued.

"As the lab-grown meat industry is developing rapidly, it is important to develop designs that expose some of its underlying constraints in order to see beyond the hype."

Human cells are fed with serum from expired blood donations

Ouroboros Steak, named after the ancient symbol of the snake eating its own tail, cuts out the need for other animals by drawing exclusively on human blood and cells.

The version on display at London's Design Museum was made using human cell cultures, which can be purchased for research and development purposes from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC). They were fed with human serum derived from expired blood donations that would otherwise have been discarded or incinerated.

The grow-it-yourself kit would include mycelium scaffolds (centre) and human serum (right)

Amuse-bouche-sized steaks are preserved in resin and laid out on a plate complete with a placemat and silverware as a tongue-in-cheek nod to American diner culture.

As part of the DIY kit, the team envisions users collecting cells from the inside of their own cheek using a cotton swab and depositing them onto pre-grown scaffolds made from mushroom mycelium.

For around three months, these are stored in a warm environment such as a low-temperature oven and fed with human serum until the steak is fully grown.

For display, the bite-sized steaks are preserved in resin

"Expired human blood is a waste material in the medical system and is cheaper and more sustainable than FBS, but culturally less-accepted. People think that eating oneself is cannibalism, which technically this is not," said Knight.

"Our design is scientifically and economically feasible but also ironic in many ways," Telhan added.

"We are not promoting 'eating ourselves' as a realistic solution that will fix humans' protein needs. We rather ask a question: what would be the sacrifices we need to make to be able to keep consuming meat at the pace that we are? In the future, who will be able to afford animal meat and who may have no other option than culturing meat from themselves?"

Ouroboros Steak was previously exhibited at the Designs for Different Futures exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Although no lab-grown meat has so far approved for sale in any part of the world, the market is estimated to be worth $206 million and expected to grow to $572 million by 2025, largely due to the increasing environmental and ethical concerns about the mass rearing of livestock for human consumption.

Among the companies hoping to bring cultured meat to market are Aleph Farms, which claims to have been the first company to make a lab-grown steak. Others have focused on substituting meat entirely, with Novameat creating a 3D-printed steak from vegetable proteins.

Soylent Green isn't as evil as it is made out to be today Spoiler of the punchline of the whole movie... "Soylent Green is people!"

In the film Soylent Green the big conspiracy is that human corpses are being recycled to make food for others to eat. While cannibalism is viewed in a negative light, it is almost socially acceptable in dire situations, which the world of Soylent Green is.

The basic problem of the Soylent Green world is that there isn't enough food energy available to feed the population due to the poisoning of the land and recent poisoning of the ocean. While the powers that be and their science teams scramble to find a long-term solution to keeping humanity alive they have to implement stopgaps.

The dead aren't going to contribute any more to society, and burning the bodies would waste the chemical energy in them. Converting them to food allows humanity to stay alive a little longer while a permanent solution is looked for.

In the final scene of the film the fear is expressed that humans will be "bred like cattle" to feed the rich. This cannot be true, because it will always take more food to grow a human than you will get out of them -- thermodynamics demands it. Soylent Green can be a stopgap while looking for a long-term solution, but you can't sustain a society on it.

No one is being bred for food. It's merely a dire situation where the powers that be are looking for a means to keep humanity alive while long-term options are being investigated.

By publicizing the Soylent Green production process (and probably getting it shut down), the protagonist has perhaps doomed humanity to starvation if an alternative is not found in time, since cannibalism was keeping humanity alive a little longer than they would have been able to live otherwise.

New York City has a population of 96 million, and only the elite pedophile's can afford spacious apartments, clean water, and natural food. The homes of the elite are fortified, with security systems and bodyguards for their tenants. Usually, they include concubines (who are referred to and used as "furniture"). The poor live in squalor, haul water from communal spigots, and eat highly processed wafers: Soylent Red, Soylent Yellow, and the latest product, far more flavorful and nutritious, Soylent Green.

I never found Soylent Green plausible. If the Earth can no longer support the number of human beings it has, then the areas that don't have enough food will go to war to get food from others, and the resulting casualties will bring Earth's population down to manageable levels.

Agenda 21 and 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is a non-binding, voluntarily implemented action plan of the United Nations with regard to sustainable development.

https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

Growing Smart Legislative Guidebook Model Statutes for Planning and the Management of Change. ( Its 1432 Pages Long ) Thanks.

DEATH DECLARATION For 2030 Agenda 21 for Sustainable Development Wide World Now.

-

18:13

18:13

What If Everything You Were Taught Was A Lie?

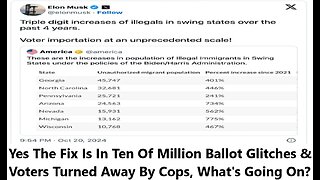

21 days agoYes The Fix Is In Ten Of Million Ballot Glitches & Voters Turned Away By Cops, What's Going On

3.65K7 -

9:34

9:34

Dr David Jockers

17 hours ago $14.20 earnedThe Shocking Truth About Butter

103K7 -

9:05

9:05

Bearing

1 day agoJaguar's Woke New Ad is SHOCKINGLY Bad 😬

43.4K106 -

7:55

7:55

Chris From The 740

17 hours ago $10.35 earnedWill The AK Project Function - Let's Head To The Range And Find Out

30K9 -

2:39

2:39

BIG NEM

13 hours agoHygiene HORROR: The "Yurt Incident"

20.7K2 -

3:19:21

3:19:21

Price of Reason

16 hours agoHollywood Celebrities FLEE the US After Trump Win! Wicked Movie Review! Gaming Journos MAD at Elon!

112K78 -

3:55:45

3:55:45

Alex Zedra

11 hours agoLIVE! Last Map on The Escape: SCARY GAME.

93.1K3 -

1:14:07

1:14:07

Glenn Greenwald

16 hours agoComedian Dave Smith On Trump's Picks, Israel, Ukraine, and More | SYSTEM UPDATE #370

189K273 -

1:09:07

1:09:07

Donald Trump Jr.

19 hours agoBreaking News on Latest Cabinet Picks, Plus Behind the Scenes at SpaceX & Darren Beattie Joins | TRIGGERED Ep.193

230K784 -

1:42:43

1:42:43

Roseanne Barr

15 hours ago $68.21 earnedGod Won, F*ck You | The Roseanne Barr Podcast #75

105K220