Premium Only Content

Why Is Title 9 IX Woman Sport Is Now Over By Law And 4 Ties Trans Gender Will Win

Why Is Title 9 IX Woman Sport June 23,1972 Great History Is Now Over By Law And New Athletic Programs are considered educational programs and activities. Title IX gives women athletes the right to equal opportunity in sports in educational institutions that receive federal funds, from elementary schools to colleges and universities. While there are few private elementary, middle school or high schools that receive federal funds, almost all colleges and universities, private and public, receive such funding.

Comparing Athletic Performances: The Best Elite Women in the World to Boys and Men Athletic and Other Athletic Trans-She-He-Them-They-Why-Etc.

https://law.duke.edu/sites/default/files/centers/sportslaw/comparingathleticperformances.pdf

https://web.law.duke.edu/sites/default/files/centers/sportslaw/Experts_T_Statement_2019.pdf

https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4851&context=lcp

A woman is a person who can give birth to a baby boy or girl vaginal delivery or caesarean sections only that it and that all its about and no more talking about it today. ? ? ? ? Etc.

Defining a ‘woman I'm afraid I am mistakenly placed in a woman's body. Apparently, I don't cook and I'm not domesticated. I am not caring and I don't think I'm sweet. Sarah Kay, known for spoken word poetry, wrote a beautiful piece about women. Her poem, “The Type”, gave new insights on how women should see themselves.

She wrote in Huffington Post: “Media attention has been paid to what it means to ‘be a woman,’ but often the conversation focuses on what it means to be a woman in relation to others…I believe these relationships are important. I also think it is possible to define ourselves solely as individuals, without comparisons or relationships.”

True enough, women are often defined and valued based on their relationships. This explains why we use labels such as ‘good wife,’ ‘mistress,’ ‘other woman.’ For every stage in a woman’s life, her identity is always associated with her relationships.

When a woman reaches her mid 20s, people wonder why she does not have a boyfriend. When a woman is at her 40s, people think she is missing a large chunk of her life if she is not married. When a woman is married, people expect her to have children.

Ask a beauty queen, a husband, and a wife on what the essence of being a woman is and most of them will surely answer: “It is childbearing or child-rearing.”

But how about a woman who cannot bear a child or a woman who remains single by choice or by act of nature?

Society’s Definition

I have high regard for women who strive to be the best daughter, best girlfriend, best wife, and best mother. All these roles should be part of our aspiration in life. Our relationships shape our lives and build our character but there is something more than what a relationship offers. Yet, culture tells us that it should define us.

Society Dictates how women should naturally maintain relationships. Hence, when a relationship fails, a woman needs to justify herself. When a married woman is caught having an affair with another man, she is immediately guilty of adultery.

But when a married man is caught having an affair with another woman, he is not yet guilty of any extramarital crime. Philippine law states that he is only guilty of concubinage if his affair is under scandalous circumstances.

READ: Laws that discriminate against women

I told my friend: “So what do we do then? Should we protest? Protest that we can also have extramarital affair and not have an automatic crime of adultery like men do, unless we do something scandalous?”

Defining the word ‘woman’

But how do you define a woman? Is it by length of time she spent on the bathroom? If she knows how to use an eyeliner, then maybe she can call herself a ‘real’ woman?

Two men told me that I should know how to apply makeup. It’s an unexpected irony to think that girls are more open about grooming and style. My inner self tells me that I shouldn’t groom myself because I am only pleasing the eyes of men. And when I aim to please the eyes of men, I allow my relationship with others to define me.

I allow culture to define me. I allow society to define me. That for me is a form of oppression.

We all have a shared picture of an ideal woman while we don’t have a concrete picture of what an ideal man should be. Yes, he should be a provider but we can disagree that he does not have to know how to drive, how to fix electric wires, how to repair a faucet, and how to play basketball. He can be tough yet he can be soft spoken.

Not a ‘woman’

I’m afraid I am mistakenly placed in a woman’s body. Apparently, I don’t cook and I’m not domesticated. I am not caring and I don’t think I’m sweet. I honestly feel I am less of a woman. But I’m hoping someday I will raise my own family and epitomize a conventional woman.

At the same time, it is within my understanding that life has many possibilities. I’m afraid to disappoint but I’m more afraid of losing myself in the course of finding and keeping people who can make me happy.

As written by Sarah Kay: “Let the statues crumble. You have always been the place. You are a woman who can build it yourself. You were born to build.”

A woman can navigate her life with her own ambitions and talents. She is not a set of hormones and norms. She has individual traits. She is capable of finding her own happiness and building her success. She has many stories and many thoughts which should be magnified and adored.

There’s more to a woman’s life than finding the man of her dreams, bearing a child, and being the best lover or homemaker. Let us set aside prejudice for women who failed in fulfilling their traditional roles and look at the other parts of her life. Relationships are pieces of who we are but they do not speak of our entire value.

If we can't define what a woman is, how can we organize politically?

I respect everyone’s pronouns – and I ask others to respect the language that defines my life. What is a woman?” This was the question asked of the Lib Dem leadership hopeful Layla Moran late last month, on the radio programmed Political Thinking with Nick Robinson. “You talked of giving straight answers to straight questions,” said Robinson. “Here’s a nice one for you, philosophical: what is a woman?”

There was a pause, before an answer that probably wasn’t as direct as Robinson had hoped. “Well,” said Moran, “a woman is a gender, it is a way to self-identify and there are lots of genders. There is male and that is biological. There is female, which is also biological. A woman is a gender identity which is more akin to being a man. Those are the opposites and then there is also non-binary, which is people who don’t identify with either.”

This seemed confusing to me. So being a man is akin to being a woman? How does that work? I asked the same question on Twitter – what is a woman? – and Naomi Wolf, no less, the author of The Beauty Myth and Vagina: A New Biography, answered that a woman is anyone who wants to be one. It is a personal choice. “Many men and trans people have thanked me for The Beauty Myth,” she wrote. “I didn’t write it only for readers born with uteri.”

The confusion continued on Twitter with a row over a tweet from Piers Morgan, in response to a CNN tweet reading: “Individuals with a cervix are now recommended to start cervical cancers screening at 25.” Morgan replied: “Do you mean women?”, and when Rosie Duffield, MP for Canterbury, liked Morgan’s tweet, she was accused of being a transphobe. Duffield then tweeted: “I’m a ‘transphobe’ for knowing that only women have a cervix...?!” Progressives who presumably want to win back those “red wall” seats called for her sacking.

I am dismayed at the persecution of trans people – and also at the bile directed towards women who are questioning a narrative in which our experience, needs and reality are too often overlooked. Why can’t we use the word “womxn”, someone asked on Twitter. It’s obvious, isn’t it? To erase the word “woman” means we cannot speak of our biology and our experience. Leftwing feminists, me included, see women as a sex class. American “choice feminism” was a disaster; feminism repackaged as capitalist attainment. The backlash is now here, and in some cases it comes in the form of an ideology that overrides the demands of women.

We don’t talk so much now about the terrible violence meted out to women – the appallingly low rate of rape convictions and the huge and growing incidence of domestic violence – because that would be to see women as still oppressed. And there is a popular narrative now that often says we’re not. For some people, victimhood has become the preserve of a tiny percentage of the population – trans and other seriously marginalized communities – who do indeed have a very hard time. But while their difficulties are recognized, women’s difficulties are considered merely the bleating's of privileged females.

If we cannot define what a woman is or name that experience, we cannot organize politically. As the radical feminist Andrea Dworkin once wrote: “Men have the power of naming, a great and sublime power. This power of naming enables men to define experience, to articulate boundaries and values, to designate to each thing its realm and qualities, to determine what can and cannot be expressed to control perception itself.”

For me, the debate around trans issues is not and never has been about toilets or changing rooms. It is about the right of women to define themselves in a system that is afraid we might do just that.

I will happily respect anyone’s pronouns and I ask other people, too, to respect the language that defines my life in a female meat suit. Men are never spoken of as prostate owners, or vehicles for their penises or testicles. I have never yet read a definition of “cis” that I identify with, even though, as a female whose gender expression matches her sex, this is apparently what I am. The fact is, when it comes to my appearance, I started wearing drag – makeup, heels, big hair – as soon as I knew that, in order to use my mind, I would have to appear on the outside entirely different to how I felt on the inside. Gender nonconformity has been an essential part of my life, as it is for so many people, whether this is apparent or not. I always liked the way the Stonewall activist Marsha P Johnson chose to call herself a “street transvestite action revolutionary”. She thought of herself not as a woman but as “a queen”.

All of us are a combination of biology and history, our bodies situated in a time and a place. I neither want to fetishize and essentialize biology nor deny it. It is different for each of us.

It is often argued on Twitter that the struggle for trans rights is the same as the struggle for gay rights. But, crucially, coming out as gay demands nothing from others but equality. There is now a demand from some activists – many of them not trans themselves; many of them men – that the class of women must be renamed.

I reject this. Am I more than a collection of body parts? Am I allowed to talk of my own life? Am I a woman simply out of choice?

What, then, is a woman? These days, I often find it is simply someone who does not agree to let misogynist men speak for us.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you move on, I wondered if you would consider taking the step of supporting the What If Everything You Were Taught Was A Lie? journalism.

It’s that time again: all eyes are on the supreme court, as we await the final decisions of the session. One year after the court overturned Roe v Wade, its approval ratings are at record lows and its legitimacy in crisis.

That should come as no surprise: a far-right movement has helped seat justices who have redefined public life through precedent-shattering decisions that most Americans do not support. In addition to taking away the right to abortion from half the country, the supreme court has enabled a deluge of money into politics, the proliferation of guns in public spaces, the gutting of environmental protections and more.

As recent revelations have made clear, some supreme court justices do not follow basic ethical standards, and an absence of limits on their power means they can operate, in many ways, above the law.

That makes the job of journalists all the more important. At the What If Everything You Were Taught Was A Lie? our reporting is produced to serve the public interest; we have no billionaire owner or shareholders to consider. And our unique, reader-supported model means that readers around the world can access the What If Everything You Were Taught Was A Lie? paywall-free journalism – whether they can afford to pay for news, or not.

The penalty for non-compliance with Title IX is withdrawal of federal funds. Despite the fact that most estimates are that 80 to 90 percent of all educational institutions are not in compliance with Title IX as it applies to athletics, such withdrawal of federal moneys has never been initiated. When institutions are determined to be out of compliance with the law, the United States Department of Education Office for Civil Rights (OCR) finds them “in compliance conditioned on remedying identified problems.”

A woman is a person who can give birth to a baby boy or girl vaginal delivery or caesarean sections only that it and that all its about and no more talking about it today. ? ? ? ? Etc.

Title IX requires that every educational institution have a Title IX Compliance Coordinator. The OCR is the primary agency charged with its enforcement. However, to date, this agency’s enforcement efforts have been inadequate. Any person, regardless of whether they have been harmed by failure of the educational institution to comply with the law, may file a Title IX complaint with the OCR which is obligated to investigate such a complaint within a specified time period. The person filing the complaint may request that his or her identity be kept confidential. Individuals who have been harmed by failure of the institution to comply have an individual right to sue under the law and almost 95% of such lawsuits having to do with athletic program violations have been successful.

There are three parts to Title IX as it applies to athletics programs: (1) effective accommodation of student interests and abilities (participation), (2) athletic financial assistance (scholarships), and (3) other program components (the “laundry list” of benefits to and treatment of athletes). The “laundry list” includes equipment and supplies, scheduling of games and practice times, travel and daily per diem allowances, access to tutoring, coaching, locker rooms, practice and competitive facilities, medical and training facilities and services, publicity, recruitment of student athletes and support services.

Title IX compliance is assessed via a total program comparison. In other words, the entire men’s and women’s programs are to be compared, not just one men’s team to the women’s team in the same sport. This broad comparative provision was intended to emphasize that Title IX does not require the creation of mirror image programs. Males and females can participate in different sports according to their respective interests and abilities. Thus, broad variations in the type and number of sports opportunities offered to each gender are permitted.

Title IX does not require equal expenditure of funds on male and female athletes. The only dollar for dollar expenditure requirement is in the athletic financial assistance area, where schools are required to spend dollars proportional to participation rates. Thus, if $200,000 is awarded in athletic scholarships and the participation ratio of male to female athletes is 50/50, $100,000 must be awarded to female athletes and $100,000 must be awarded to male athletes. In other areas, the equality standard is one of equal opportunity.

With regard to Title IX’s participation requirements, a school can meet the standard via three independent tests. The first test is a mathematical safe harbor. If the school offers athletic participation opportunities (number of individual athlete participation slots, not numbers of teams) proportional to the numbers of males and females in the general student body, the school meets the participation standard. If the school does not meet this mathematical test, it may be deemed in compliance if it can (1) demonstrate consistent expansion of opportunities for the underrepresented gender over time or (2) show that the athletic program fully met the interests and abilities of the underrepresented gender. The courts have ruled that “boys are more interested in sports than girls” is not an acceptable defense to lack of equitable participation opportunities.

Under Title IX there are no sport exclusions or exceptions, so football is included under the law. Individual participation opportunities (numbers of athletes participating rather than number of sports) in all men’s sports and all women’s sports are counted in determining whether a school meets the Title IX participation standard. The basic philosophical underpinning of Title IX is that there cannot be an economic justification for discrimination. The school cannot maintain that there are revenue production or other considerations that mandate that male athletes receive better treatment or participation opportunities than female athletes. A good analogy would be that a school cannot say that it cannot afford to provide wheelchair access for students with physical disabilities as required under the Americans With Disabilities Act because the football team needs the money in order to maintain its current level of revenue production. Similarly, a school cannot say that it cannot afford to provide participation opportunities for an underrepresented gender.

It is also important to recognize that Title IX does not require the reduction of opportunities for male athletes in order to increase opportunities for female athletes. Schools that choose this manner of compliance are not meeting the spirit of discrimination laws, which is to bring members of the disadvantaged group up to the participation or benefit levels of the advantaged group rather than to bring male athletes down to the current level of poor treatment or no opportunity to play experienced by female athletes. If athletic budgets do not increase and schools desire to maintain current levels of participation for male athletes and increase participation levels of female athletes, the solution is to give all teams a smaller portion of the budget pie.

Typically, athletic departments have refused to “tighten the belt” of popular men’s sports like football, and have cut men’s non-revenue producing sports instead and blamed it on Title IX. Three points should be made in this regard: (1) it is dysfunctional to “pit the victims against the victims” — men’s non-revenue sports against women’s sports, both of which have been traditionally underfunded, (2) over 80% of all college football programs and almost all high school football programs lose money, and (3) nothing negative would happen to men’s revenue-producing sports if their budgets were decreased across the board with all schools and all teams lowering expenditures simultaneously so the playing field is kept level. In fact, football expenditures have continued to increase at rates higher than inflation. For example, according to National Collegiate Athletic Association gender equity studies comparing 1992 and 1997 budgets, average per school dollar increases to Division I-A men’s sports operating budgets over the last five years were three (3) times the increases to women’s sports operating budgets (men=$1.37 million/women=$400,000). Sixty-three percent or $872,000 of the $1.37 million amount went to football. Further, the $872,000 increase in football budgets exceeded the total average operating budget amount spent on all of women’s sports ($662,000/yr) by more than $200,000.

While there are considerable misconceptions and inaccuracies surrounding the discussion of Title IX as it applies to athletic programs, it is important to understand the basic premise of the law: Title IX is an important federal civil rights act that guarantees that our daughters and sons are treated in a like manner with regard to all educational programs and activities, including sports.

Title IX and Sex Discrimination Title IX

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) enforces, among other statutes, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. Title IX protects people from discrimination based on sex in education programs or activities that receive federal financial assistance. Title IX states:

No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.

Scope of Title IX

Title IX applies to schools, local and state educational agencies, and other institutions that receive federal financial assistance from the Department. These recipients include approximately 17,600 local school districts, over 5,000 postsecondary institutions, and charter schools, for-profit schools, libraries, and museums. Also included are vocational rehabilitation agencies and education agencies of 50 states, the District of Columbia, and territories of the United States.

A recipient institution that receives Department funds must operate its education program or activity in a nondiscriminatory manner free of discrimination based on sex, including sexual orientation and gender identity. Some key issue areas in which recipients have Title IX obligations are: recruitment, admissions, and counseling; financial assistance; athletics; sex-based harassment, which encompasses sexual assault and other forms of sexual violence; treatment of pregnant and parenting students; treatment of LGBTQI+ students; discipline; single-sex education; and employment. Also, no recipient or other person may intimidate, threaten, coerce, or discriminate against any individual for the purpose of interfering with any right or privilege secured by Title IX or its implementing regulations, or because the individual has made a report or complaint, testified, assisted, or participated or refused to participate in a proceeding under Title IX. For a recipient to retaliate in any way is considered a violation of Title IX. The Department’s Title IX regulations (Volume 34, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 106) provide additional information about the forms of discrimination prohibited by Title IX.

OCR’s Enforcement of Title IX

OCR vigorously enforces Title IX to ensure that institutions that receive federal financial assistance from the Department comply with the law. OCR evaluates, investigates, and resolves complaints alleging sex discrimination. OCR also conducts proactive investigations, through directed investigations or compliance reviews, to examine potential systemic violations based on sources of information other than complaints. In addition to its enforcement activities, OCR provides information and guidance to schools, universities and other educational institutions and agencies to assist them in voluntarily complying with the law.

June 2017 marked the 45th anniversary of Title IX, landmark legislation that changed the landscape of high school and collegiate athletics in the United States. Title IX of the Education Amendments states, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” The legislation is most commonly associated with a dramatic growth in girls’ and women’s sports participation, while more recent events signal the ways in which Title IX may precipitate other important changes. One potentially key area is transgender participation in sport, from locker rooms to lacrosse teams; another has seen Title IX employed in a new generation of activism focused on sexual assault and harassment on college campuses (some even suggest that today’s college students will associate Title IX more with consent and gender identity than with athletics). All this demonstrates the resilience and power of Title IX—and its continued relevance at and beyond 45.

Five years ago, in commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the legislation, my colleague Nicole LaVoi and I published an article, “Playing but Losing: Women’s Sports after Title IX,” in Contexts. We outlined several persistent forms of inequality in women’s sports, drawing upon sociological research as we considered inequities in media coverage and gender representation in key decision-making positions, including coach and athletic director. Title IX does not legislate either, though we argued that one would reasonably expect, given the millions of girls and women now participating in and excelling at sports (even professional and Olympic-level), we should by now be approaching some semblance of parity in media and management.

Five more years down the line, however, the mainstream sport media continue to ignore the myriad competitive accomplishments of women’s sports (with the exception of major international sports events, like the Women’s World Cup or the Olympics). For example, in longitudinal research that has tracked the quantity and quality of coverage of men’s and women’s sports in televised news and highlight shows over the past 25 years, we found that coverage of women’s sports remains dismally low— no more than 2-3% of the total coverage. In fact, the coverage of women’s sports was lower in 2014 than in 1989 when the study first began. Qualitatively, there have been some important shifts in the way women are represented. We found less content focused on sexually objectifying female athletes or positioning women as the targets of humorous sexualization. Instead, women’s sports were presented in dull and lackluster ways that, when compared to the exciting delivery of men’s sports, was sure to send viewers the message that women’s sports are, well, boring. Asserting that audiences are not interested in women’s sports reinforces the idea that they don’t need much coverage, and, in turn, uninteresting coverage dampens a lot of viewers’ interest.

As far as representation in coaching, Nicole LaVoi finds the representation of women in coaching positions has remained relatively stable over the past 10 years—around 40%. Women continue to encounter structural and cultural barriers to their participation, including sexism and racism, homophobia, the gendered division of labor in families, among other barriers. A recent survey conducted by the Women’s Sports Foundation found women coaches were more likely to state they experienced gender bias on the job, were subject to different expectations than their male counterparts, and believed male coaches were given more professional advantages.

In our forthcoming book, Michael Messner and I argue that these divergent trends illustrate “the unevenness of social change.” Rather than viewing the progression toward gender equality as either an unfinished revolution or a stalled revolution, we show that both changes and continuities in gender in/equality happen simultaneously. If the next 45 years, as we’re seeing now, continues a trajectory of rape culture, harassment, and assault as barriers to participation in higher education and collegiate athletics, the legislation will certainly retain its status as a vital tool for social change.

Last winter, even those who don’t generally follow sports heard about Mack Beggs, a transgender boy in Texas who won the state high school championship in girls’ wrestling. Mack identifies as male and would have preferred to compete with other boys. But the state interscholastic athletics league in Texas prohibits students from competing as anything other the sex noted on their birth certificate. Even as science tells us that gender can hardly be reduced to whatever is visible to a doctor glancing considering a newborn’s genitalia, the league refused to accept any other evidence regarding whether Mack is male or female. This disregards the entire notion of gender identity, despite its having been widely validated as a real and salient aspect of an individual’s identity. And it disregards Mack’s own sincere and consistent declaration that his gender identity is male.

In most of the rest of the U.S., Mack would be eligible to compete in boys’ sports. Just six states’ interscholastic athletics associations classify athletes by the gender designation on their birth certificates. Whether Title IX prohibits schools from excluding or assigning transgender athletes because of their birth certificates has yet to be conclusively decided, but even absent a legal requirement more than half of state athletic associations permit transgender athletes to compete according to their gender identity (with some conditions). Even in higher levels of competition, such as NCAA championships and the Olympic Games, Mack would be eligible to compete as a male. This is a notable contrast, since high school sports in Texas purportedly exist to develop character and foster educational values; we should, therefore, expect Texas high school sports to be more inclusive than the Olympics, which showcase elite human athleticism. Instead, Mack could end up excluded from sports altogether—his recent championship win led many to question whether, if he cannot compete with boys, he should be allowed to compete with girls.

Transgender athletes in other states are successfully competing in high school sports. For example, the Hartford Courant recently profiled a Connecticut high school track and field athlete named Andreya Yearwood. Though assigned a male sex at birth, Andreya has a female gender identity and is regarded as female by her family, friends, teachers, coaches, and teammates. Connecticut defers to Cromwell High School’s decision that Andreya is eligible for girls’ sports, because that is consistent with how she is presents and is accepted in all facets of her life. Cromwell officials did not have to consider any criteria other than Andreya’s female gender identity to make this decision; the athletic association does not permit schools to probe athletes’ genitalia, chromosomes, or hormones. Their only role is to determine whether the athlete’s gender identity is “bona fide”—which is to say, that the athlete is legitimately transgender and not seeking an unfair athletic advantage (a problem, it is worth noting, that is entirely hypothetical).

Inclusive policies like Connecticut’s make a significant positive difference to athletes like Andreya. Her parents said that her ability to compete as the girl she knows herself to be is liberating, like a “weight lifted off of her shoulder.” Like any high school athlete, she has benefited from the confidence and community that sports develop. These benefits are particularly important to transgender students, who face a higher risk of bullying, isolation, and low body esteem, any of which can undermine a student’s academic progress and emotional well-being. Andreya’s teammates and even her opponents have reportedly greeted her participation with support and respect. And their educational experience is enriched by the opportunity to discover how diverse and unrestrictive the label “female” really is.

When Andreya won two state championship titles earlier this year, some argued that being transgender gave her an unfair advantage. However, this argument wrongly presumes that (anatomically) female athletes are categorically inferior. Though there are generalizable physical differences between male and female bodies, general differences do not conclusively determine that Andreya’s success owes to her anatomically male body. Many nontransgender female athletes compete at or near Andreya’s level, and it is certainly possible that Andreya would be a top-tier athlete even if she had been born into a different body.

Additionally, criticism of transgender athletes’ participation focuses selectively on advantages that may be attributed to one’s transgender status without taking into account myriad of physical, social, and other factors that contribute athletic advantage and disadvantage. There are rarely calls to exclude nontransgender girls whose height, musculature, or other physical characteristics are outside the range of the typical female, nor are there calls to exclude those athletes whose access to economic resources has given them a competitive advantage by allowing them high quality equipment or training. A high school team with more seniors than freshmen is not disqualified, even though the generalizable physical differences between an 18- and a 14-year-old are comparable if not more different than those between anatomical males and females.

But the strongest argument for letting transgender athletes play is hinted at in the text of the Connecticut interscholastic athletic association’s policy itself. It would be “fundamentally unjust,” it says, to preclude a student from participating according to gender identity. The benefits of inclusion to athletes like Andreya, her teammates, and even her competitors simply outweigh whatever harm could occur from athletes’ already unequal skills and advantages. Those who are more upset by a transgender girl beating a nontransgender girl than they would be by the exclusion of that transgender girl reveal their values as discordant with those of interscholastic sport. Implicit in the Connecticut policy is the notion that if the stakes of high school sports are too high to justify making room for athletes like Andreya and Mack, then the stakes should change, not the kids. Texas and its fellow birth-certificate states denigrate the participant-focused mission of high school sports.

Assertions that college athletes are employees with the right to collectively bargain often trigger arguments about unfairness and ruining the spirit of collegiate sport. Such responses follow high profile legal challenges brought by former and current NCAA Division I football and basketball players seeking changes in rules governing their status as employees with the right to organize (College Athletes Players Association v. Northwestern University), business practices that suppress player value and violate federal anti-trust laws (O’Bannon v. NCAA), access to educational benefits (McCants & Ramsey v. University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and the NCAA), health and safety (Arrington v. NCAA), and the general regulatory system that traps athletes in a nest of rules that allegedly violates federal anti-trust law (Jenkins v. NCAA). For their part, NCAA Division I athletic directors, commissioners, and officials have branded the dialogue around the employment rights of college athletes as superficial maneuvers by athletes seeking “pay for play.” High school athletes, they argue, could begin to look at college as a way of “making money …as opposed to getting an education,” should collegiate athletes be compensated directly.

Labor scholars will recognize a classic management response to workers’ attempts to influence an array of issues that affect their lives, including length of work week, the manner in which workers are evaluated and controlled by supervisors, workplace health and safety issues, health care and medical coverage, professional development and educational benefits, disability insurance, and fair compensation in relationship to value of the work performed. As the NCAA and other organizations cast the college football and basketball plaintiffs’ grievances as nothing other than the complaints of selfish, greedy, indulgent, ungrateful, and unduly privileged male athletes, Title IX has emerged as an unlikely tool of resistance to the push for professionalization for college athletes. This federal legislation, however imperfect, is credited with increasing opportunities for female athletes in college sport and fostering efforts toward gender equity. And college sport officials have long deployed Title IX as a politically convenient mechanism for sowing misunderstanding, invoking the legislation without nuanced consideration of whether it applies to the situation at hand, under what circumstances it might, and whether its gender equity mandate unilaterally forbids college athletes from being treated as employees. In effect if not intention, athletes’ concerns regarding whether college sport officials have built an industry on unfair labor practices is set up as if it is in opposition to the rights of female athletes to participate in sport under Title IX.

This juxtaposition is troubling for several reasons. First, comparing the terms and conditions under which college athletes in the sports of football and basketball play and compete with standards established under common law to define an employee presents a straightforward conclusion: these athletes are employees. They perform a service to their institutions, contribute to the economic benefit of the enterprise, and receive some amount of compensation (generally in the form of tuition benefits). Athletes perform under the supervision and direction of coaching staffs and, from NCAA data and numerous studies of other conferences (Big Ten, PAC 12), it is clear that the time demands of their sport rival those of most full-time workers, often exceeding 40 hours a week. Even 60 hours a week in practice, travel, and play is not uncommon during a given sport’s season.

Second, rather than including female athletes among those who may benefit from changes to an unjust regulatory system around their athletic labor, the argument sets female advancement up as the foil. That is, opponents assert, “if college football and basketball players are recognized as workers,” it will result in the loss of sports and opportunities for women. This very same argument was used when Title IX arrived on the scene in the 1970s. Many wrung their hands and said that applying Title IX to athletic departments would “kill the goose that laid the golden egg”—the legislation, they said, was a threat to profitability of college football and, by extension, to education funding. And yet, since the 1970s, college football has flourished in the United States.

Third, at its foundation, Title IX relies on the characterization of college sports as extracurricular activities. An objective analysis of college sport reveals, though, that it bears little to any resemblance to other “student activities”. The expansion of the regulatory system around college athletes and the surveillance mechanisms put in place to enforce these restrictions present a level of scrutiny and supervision seen nowhere else in voluntary legitimate extracurricular activities. What member of the student paper must abide by a 450-page manual that maps out an elaborate rules structure voted on by authorities with significant conflicts of interests and ties to corporate profit centers? What marching band member is required to disclose personal financial records, car registrations, personal associates and the nature of those relationships, daily activities, or submit to a background check?

Fourth, not all college sports are the same. Some have been developed to compete financially and structurally with major professional leagues (MLB, NBA, NFL) in order to generate revenue and mass audiences, while others are designed to encourage participation. While there is a general assumption that all college sports fall under the umbrella of Title IX, not all physical activity is recognized as being subject to its reach (as has been clarified on numerous occasions when the sport of cheerleading, for example, has been considered).

And fifth, doomsday scenarios in which colleges and collegiate sport organizations are bankrupted by greedy college athletes demanding employee status must be revealed as nothing more than union-busting rhetoric. Many collegiate athletic departments argue that they are already unprofitable, and this framing is readily accepted, though few have bothered to check these claims. Instead, the departments report their finances as needed to maintain non-profit status. Framing this argument as a fight over the viability of college sport further obscures how profit and loss is reported within university and athletic department accounting systems, where a profit can easily become a loss simply through a transfer of funds from department to department across an institution. Not unlike professional sport commissioners and owners who plead financial distress when they undertake negotiations with athletes, conference commissioners, the NCAA president, and athletic directors claim poverty even as their institutions build expansive new athletic facilities and governing bodies negotiate television rights for their games.

In the 21st century, getting clear on how the college sport industry works and what it takes to treat all athletes fairly, equitably, and humanely is a worthy project. Protecting the status quo means protecting a system that has engaged in economic exploitation and socially oppressive practices for far too long. Using Title IX as a means of maintaining that status quo not only misrepresents the fundamental purpose of its civil rights mandate, it actively undermines that mission.

History of Title IX June 23, 1972

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 is enacted by Congress and is signed into law by President Richard Nixon, prohibiting sex discrimination in any educational program or activity receiving any type of federal financial aid.1 Rep. Patsy Mink is recognized as the major author and sponsor of the bill, and Rep. Edith Green and Sen. Birch Bayh also made significant contributions.

May 20, 1974

Sen. John Tower proposes the “Tower Amendment,” which would exempt revenue-producing sports from determinations of Title IX compliance. The amendment is rejected.2

July 1974

In the spirit of Sen. Tower’s failed amendment, Sen. Jacob Javits submits an amendment directing the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) to issue regulations that provide for “reasonable provisions considering the nature of particular sports.”2 It argues that event and uniform expenditures on sports with larger crowds or more expensive equipment do not have to be matched in sports without similar needs.

May 27, 1975

President Gerald Ford signs the final version of Title IX—which includes Sen. Javits’ proposed athletics regulations from July 20, 1974—and submits it for congressional review.3

July 8, 1975

Rep. James O’Hara introduces “a bill to amend Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972” (H.R. 8394), which proposes that sports revenues first be used to offset the cost of that sport, and only then to support other sports. The proposed change would effectively alter Title IX’s coverage in athletics. This bill dies in committee before reaching the House floor.4

July 21, 1975

Congress reviews and approves Title IX regulations and rejects the following resolutions and bills that had been advanced in an attempt to disprove the athletics regulations2:

June 5, 1975: Sen. Jesse Helms condemns Title IX in its entirety (S.Con.Res.46).

June 17, 1975: Rep. James G. Martin disapproves of Title IX in its entirety (H.Con.Res.310) and specifically as it pertains to intercollegiate athletics (H.Con.Res.311).

July 16, 1975: Sens. Paul Laxalt, Carl T. Curtis and Paul J. Fannin disapprove of the application of Title IX to intercollegiate athletics (S.Con.Res.52).

July 21, 1975: Sen. Helms introduces “a bill to amend Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, and to preserve academic freedom” (S. 2146) in an attempt to prohibit the application of Title IX regulations to athletics in situations in which participation in those athletic activities are not a required part of the institution’s curriculum. Sen. Helms would reintroduce S. 2146 as S. 535 in 1977, though neither would be passed.

Title IX federal regulations are issued in the area of athletics. High schools and colleges are given three years, and elementary schools one year, to comply.

February 17, 1976

NCAA files a lawsuit challenging the legality of Title IX. The suit would be dismissed in 1978.5

July 15, 1977

Sens. Tower, Dewey F. Bartlett, and Roman Hruska introduce S. 2106, proposing to exclude revenue-producing sports from Title IX coverage. The bill dies in committee before reaching the Senate floor.2

July 21, 1978

Deadline for high schools and colleges to comply with Title IX athletics requirements.6

December 11, 1979

HEW issues final policy interpretation on “Title IX and Intercollegiate Athletics.”6 Rather than relying exclusively on a presumption of compliance standard, the final policy focuses on each institution’s obligation to provide equal opportunity and details the factors to be considered in assessing actual compliance: participation, benefits and treatment, and athletic financial assistance. This also marks the creation of the “three-prong test” (sometimes called the “three-part test” or “equal accommodations test”) still used today to gauge participation compliance.7

May 4, 1980

The U.S. Department of Education (ED) begins operating after its creation a year earlier and is given oversight of Title IX through the Office for Civil Rights (OCR).8

February 28, 1984

Grove City v. Bell limits the scope of Title IX, effectively taking away coverage of athletics except for athletic scholarships. The Supreme Court concludes that Title IX only applies to specific programs (i.e., a school’s office of student financial aid) that receive federal funds.9 Under this interpretation, athletic departments are not necessarily covered.

March 22, 1988

The Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987 is enacted into law over the veto of President Ronald Reagan.10 This act reverses Grove City v. Bell, restoring Title IX’s institution-wide coverage. If any program or activity in an educational institution receives federal funds, all of the institution’s programs and activities must comply with Title IX.

September 6, 1988

Haffer v. Temple University Title IX athletics lawsuit won by plaintiff female athletes gives new, stronger direction to athletic departments regarding their budgets, scholarships, and participation rates of male and female athletes.11

April 2, 1990

Valerie M. Bonnette and Lamar Daniel author Title IX Athletics Investigator’s Manual, issued by OCR and used to assist athletic departments with enforcement and compliance issues.12

February 26, 1992

In Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools, the Supreme Court rules that monetary damages are available under Title IX.13 Previously, only injunctive relief was available (i.e., the institution would be enjoined from discriminating in the future; effectively, probation).

March 1992

Shortly after the Franklin decision, the NCAA completes and publishes a landmark gender equity study of its Division I member institutions, finding significant discrepancies in participation rates and funding between women’s and men’s athletic programs. It also shows that fewer than 50% of women’s teams have female head coaches, as do just 1% of men’s teams, and that “male/female salary discrepancies are significant in almost all instances.”14

October 20, 1994

Sponsored by Sen. Carol Moseley Braun (S. 1468) and Rep. Cardiss Collins (H.R. 921) a year earlier, the Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act (EADA) is officially enacted.15 It requires that any co-educational institution of higher learning that participates in any federal student financial aid program and that sponsors an intercollegiate athletics program must disclose certain information concerning its athletics program. Under the EADA, annual reports are required, the first for each institution due no later than October 1, 1996. You can find the most recently reported data for these colleges and universities here.

January 16, 1996

OCR issues a clarification of the three-prong test, reiterating that institutions may choose any one of three independent tests to demonstrate that they are effectively accommodating the participation needs of the underrepresented sex.16

October 1, 1996

All institutions of higher education must make available for the first time, to all who inquire, specific information on their intercollegiate athletics department, as required by the EADA. In subsequent years, this date would be October 15.15

November 21, 1996

A federal appeals court upholds a lower court’s ruling in Cohen v. Brown University, holding that Brown University illegally discriminated against female athletes.17 Brown argues that it did not violate Title IX because women are less interested in sports than men. Both the district court and the court of appeals reject Brown’s argument. Many of the arguments offered by Brown are similar to those relied upon by colleges and universities all over the country.

July 23, 1998

OCR issues a Dear Colleague letter clarifying that a college or university’s total athletic scholarship budget must mirror the institution’s percentage of athletes of each gender, within 1%. “Thus, for example, if men are 60% of [a school’s] athletes, OCR would expect that the men’s athletic scholarship budget would be within 59%-61%” of the total scholarship budget for all athletes, after controlling for legitimate nondiscriminatory reasons for any larger disparity.18

February 20, 2001

The Supreme Court issues a decision in Brentwood v. Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Association, holding that a high school athletic association is a “state actor” and thus subject to the Constitution.19 This affirms that the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment applies to athletic associations in gender equity suits.

December 17, 2001

Communities for Equity v. Michigan High School Athletic Association is decided, holding the state athletic association liable under Title IX, the Equal Protection Clause, and Michigan state law for discriminating against girls by forcing six girls’ sports teams, but no boys’ teams, to compete in nontraditional and/or disadvantageous seasons.20

January 17, 2002

The National Wrestling Coaches Association, Committee to Save Bucknell Wrestling, Marquette Wrestling Club, Yale Wrestling Association, and the College Sports Council (representing national collegiate coaches associations for men’s and women’s swimming, men’s and women’s track and field, men’s wrestling and men’s gymnastics), file a suit alleging that Title IX regulations and policies are unconstitutional. It would be dismissed two years later.21

June 27, 2002

Secretary of Education Rod Paige announces the establishment of a Commission on Opportunities in Athletics. The stated purpose of the Commission is “to collect information, analyze issues and obtain broad public input directed at improving the application of current Federal standards for measuring equal opportunity for men and women and boys and girls to participate in athletics under Title IX.”22

October 29, 2002

Following her death one month prior, Title IX is renamed the “Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act” in honor of its major author.23

July 11, 2003

OCR issues “Further Clarification of Intercollegiate Athletics Policy Guidance Regarding Title IX Compliance.”24 This Further Clarification reaffirms the validity and effectiveness of long-standing administrative regulations and policies governing this application.

March 17, 2005

ED issues “Additional Clarification of Intercollegiate Athletics Policy: Three-Part Test – Part Three,”25 significantly weakening Title IX. Schools can now simply send out an email survey to their female students, asking them what additional sports they might have the interest and ability in playing. And if the survey responses do not show enough interest or ability, they do not have to add any sports—and are presumed in compliance with Title IX.

April 20, 2010

ED issues a policy guidance which rescinds the aforementioned “Additional Clarification” and all related documents, including the recommended survey.26

April 4, 2011

ED issues a policy guidance which makes clear that Title IX’s protections against sexual harassment and sexual violence apply to all students, including athletes. It addresses athletics departments in particular in its requirement that schools to use the same procedures that apply to all students to resolve sexual violence complaints involving student athletes.27

April 24, 2013

OCR issues a Dear Colleague letter reminding schools and institutions that retaliation is a violation of federal law.28

June 25, 2013

OCR issues a Dear Colleague letter and creates literature to improve the graduation rates of young parents at secondary schools and postsecondary institutions. The literature stresses that students must be allowed to return to all former academic and extracurricular activities.29

May 14, 2014

OCR issues a Dear Colleague letter that reiterates to public charter schools that they are subject to the same federal civil rights laws, regulations and guidance that apply to other public schools.30

April 24, 2015

OCR issues a Dear Colleague letter to remind school districts, colleges and universities that if they receive federal financial assistance, they must assign at least one employee as their Title IX coordinator.31

May 13, 2016

ED and DOJ issue guidance on protecting transgender students under Title IX.32 ED outlines that the prohibition of sex discrimination encompasses discrimination based on a student’s gender identity, including transgender status. In relation to athletics, schools are permitted to operate sex-segregated athletic teams, but they cannot adopt requirements that are based on stereotypes about differences between transgender students and cisgender students. This interpretation allows age-appropriate, tailored requirements that are based on current medical research about the impact of student participation on competitive fairness and physical safety.

February 22, 2017

OCR rescinds Title IX guidance on transgender students issued on May 13, 2016.33

September 22, 2017

OCR withdraws policy guidance issued on April 4, 2011, which had clarified that Title IX’s procedures and protections against sexual harassment and sexual violence apply to all students, including athletes.34 However, this withdrawal has since been rescinded.

August 14, 2020

Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos enacts several changes to Title IX regarding sexual harassment and misconduct that threaten to discourage reporting by survivors and stretch schools’ resources.35

August 26, 2020

OCR rescinds guidance on public charter schools and the requirement that schools have a designated Title IX coordinator, issued on May 14, 2014, and April 24, 2015, respectively.36,37

January 20, 2021

President Joe Biden releases Executive Order 13988, “Preventing and Combating Discrimination on the Basis of Gender Identity or Sexual Orientation,” which states, “All persons should receive equal treatment under the law, no matter their gender identity or sexual orientation.” According to the order, laws that prohibit sex discrimination, including Title IX, “prohibit discrimination on the basis of gender identity or sexual orientation, so long as the laws do not contain sufficient indications to the contrary.”38

March 8, 2021

President Biden releases Executive Order 14021, “Guaranteeing an Educational Environment Free From Discrimination on the Basis of Sex, Including Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity.” It states the Biden Administration’s objective to guarantee to all students “an educational environment free from discrimination on the basis of sex, including discrimination in the form of sexual harassment, which encompasses sexual violence, and including discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity,” citing Title IX as applicable governing law.39

June 16, 2021

ED issues an interpretation to clarify the protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation and discrimination based on gender identity under Title IX in light of the Supreme Court’s decision in Bostock v. Clayton County.40

States with bans

So far, 18 states with Republican-controlled state legislatures have banned transgender athletes from competing in sports that are consistent with their gender identity.

Those states that have passed bans on transgender youth in sports in addition to Iowa, are Montana, Idaho, South Dakota, Utah, Arizona, Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana, Alabama, Florida, South Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia, Indiana and Mississippi.

Some of those bans have not gone into effect yet and are on hold due to temporary injunctions such as those in Idaho, West Virginia, Indiana, Utah and Montana, where that injunction applies only to bans in higher education and not K-12.

Bonamici introduced an amendment which would prohibit institutions of higher education from requiring athletes to provide reproductive and sexual health information, including information about an athlete’s menstrual cycle.

“It is never okay to ask for unnecessary menstrual and reproductive information from women and girls as a basis for determining eligibility for sports,” she said.

Foxx said she disagreed with the amendment, because “this amendment strips out the underlying bill.”

Foxx said it was a “radical attempt to erase women.”

“H.R. 734 is about protecting women from discrimination and unfair playing fields,” Foxx said. “This amendment prevents the achievement of both goals.”

Bonamici’s amendment was voted down in a voice vote.

The committee also marked up and passed a second bill, H.R. 5, the “Parents Bill of Rights Act” introduced by Rep. Julia Letlow, R-La. It also passed on a 25-17 party-line vote.

That bill would require public schools to provide materials for parents to review, such as books in the school library, curriculum and budgets. If those schools do not comply, they could lose federal funding.

The bill would also limit classwork and books that deal with issues related to race and sex. House Majority Leader Steve Scalise, Republican of Louisiana, is planning to bring the parents bill of rights to a floor vote as early as March 20, according to Politico.

Emergency Childbirth 1961 US Navy Vintage Educational Film ** GRAPHIC **

https://rumble.com/v281x8a-emergency-childbirth-1961-us-navy-vintage-educational-film-graphic-.html

This Film From the US Navy Department (1961) shows how to render necessary assistance in the emergency delivery of a baby. Tells how to determine when delivery is too imminent to risk transportation to a hospital and outlines procedures to follow during and immediately after delivery.

-

8:23:08

8:23:08

What If Everything You Were Taught Was A Lie?

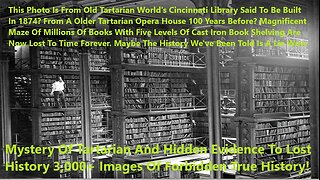

15 days agoMystery Of Tartarian And Hidden Evidence To Lost History 3,000+ Images Of Forbidden History

3.89K4 -

DVR

DVR

Josh Pate's College Football Show

4 hours ago $0.09 earnedCFP Changes Coming | Transfer Portal Intel | Games Of The Year | Head Coaches Set To Elevate

4.62K -

1:21:17

1:21:17

Donald Trump Jr.

6 hours agoWhat are These Mystery Drones? Plus Inside the Swamp’s CR. Interview with Lue Elizondo | TRIGGERED Ep.200

96K100 -

37:54

37:54

Kimberly Guilfoyle

7 hours agoAmerica is Healing, Plus Fani Willis Disqualified, Live with Shemane Nugent & Mike Davis | Ep. 182

72.8K42 -

7:38

7:38

Game On!

4 hours ago $0.48 earnedThe picks you need for Thursday Night Football!

11.6K -

55:30

55:30

LFA TV

1 day agoBible Prophecy Was Center Stage in 2024 | Trumpet Daily 12.19.24 7PM EST

23.6K1 -

DVR

DVR

Quite Frankly

7 hours ago"Divine Providence & The Three Wisemen" ft. Fr. Jason Charron 12/19/24

17K3 -

1:58:28

1:58:28

Redacted News

6 hours agoBREAKING! Elon Musk DESTROYS spending bill, Ron Paul pushes to make him Speaker | Redacted News

130K298 -

51:06

51:06

VSiNLive

4 hours agoCollege Football Playoff & Bowl Game Best Bets! | VSiN College Football Betting Podcast LIVE

33.1K1 -

1:34:33

1:34:33

Candace Show Podcast

5 hours agoHow We Faked The Moon Landing With Bart Sibrel | Candace Ep 124

62.8K233