Premium Only Content

CIA Archives: China: The Roots of Madness - The Cultural Revolution and Mao Zedong's Impact

https://thememoryhole.substack.com/

The film offers a critical analysis of China's cultural and political history, exploring the causes and consequences of the country's cultural revolution and the rise of Mao Zedong's Communist Party.

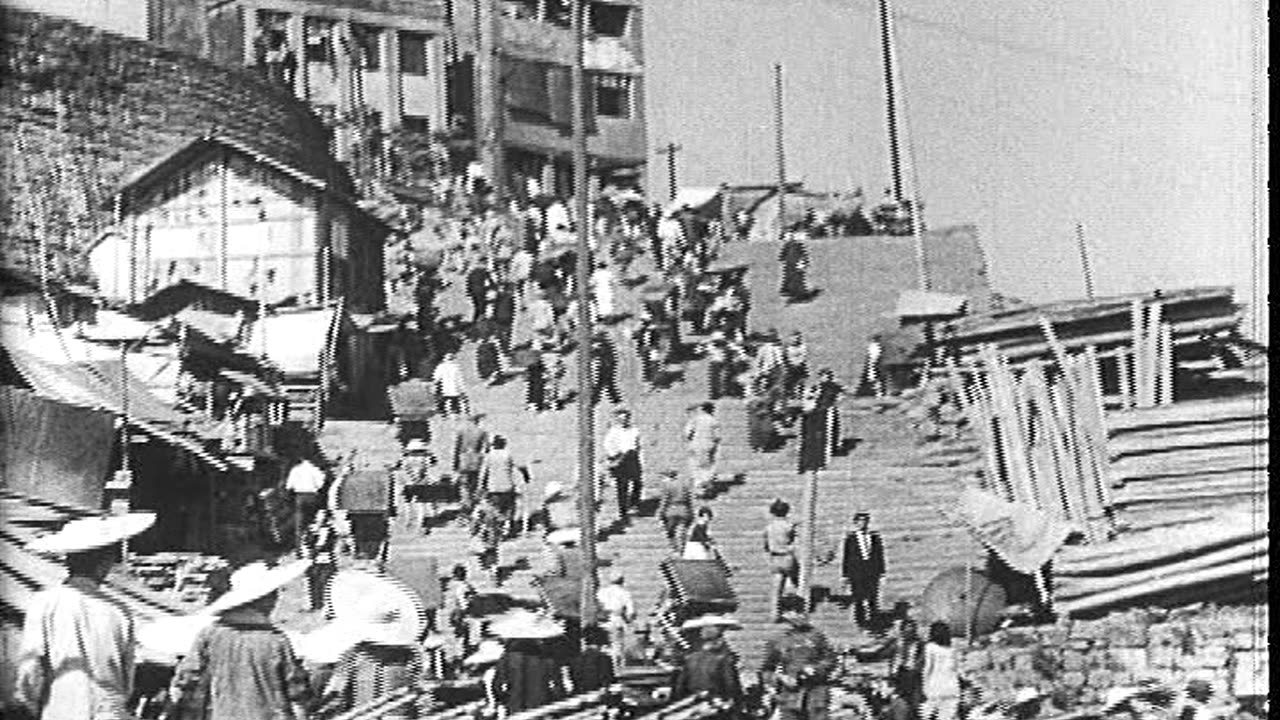

The film uses a combination of historical footage, interviews, and commentary from experts to provide a comprehensive overview of China's past, including its dynastic rule, imperialism, and the Chinese Civil War. It then delves into the Communist Party's ascent to power, its political and economic policies, and the brutal tactics used to suppress dissent and opposition.

The film examines the psychological and sociological factors that led to the Chinese people's acceptance of Communist rule, such as the appeal of a collective identity and the promise of equality and prosperity. However, it also highlights the human toll of the cultural revolution, including the persecution of intellectuals and dissidents, the destruction of cultural heritage sites, and the displacement of millions of people.

"China: The Roots of Madness" is a powerful and thought-provoking documentary that provides a deep understanding of China's complex history and the impact of Mao's leadership on the country's development. It offers a cautionary tale of the dangers of authoritarianism and the importance of protecting individual freedoms and human rights.

Some of the notable individuals featured in the film include:

Harrison E. Salisbury (journalist and author)

George Urban (journalist and author)

Dr. Stuart Schram (sinologist and professor of politics)

Dr. Franz Schurmann (historian and sociologist)

Dr. Michael Lindsay (political scientist and professor)

Dr. John K. Fairbank (historian and sinologist)

Dr. Edgar Snow (journalist and author)

Dr. Han Suyin (writer and physician)

Dr. Joseph Needham (scientist and sinologist)

Dr. Jean Pasqualini (historian and sinologist)

China: The Roots of Madness is a 1967 Cold War era, made-for-TV documentary film produced by David L. Wolper, written by Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Theodore H. White with production cost funded by a donation from John and Paige Curran. The film has been released under Creative Commons license. It won an Emmy Award in the documentary category.

The film attempts to analyze the anti-Western sentiment in China from the official American perspective, covering 170 years[citation needed] of China's political history, from Boxer Rebellion of the Qing Dynasty to Red Guards of Cultural Revolution. The film focuses on the power struggle between the Kuomintang and the Communist Party of China, amid heavy political intervention from Moscow, with Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong playing the pivotal role at the center stage.[1][2]

Introduction

10:59

10:59

10:58

11:00

10:59

10:01

2:02

The documentary film was made for television in 1967, during the Cold War. It was written by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Theodore H. White, directed by Mel Stuart, edited by William T. Cartwright, and produced by David L. Wolper.[3] Production costs were funded by a donation from John and Paige Curran.[1] The film has been released under Creative Commons license.[1]

White's access to important political figures of the time allowed him to create some rare footage, which included the wedding of Chang and the funeral of Sun. The film won an Emmy Award in the documentary category.[citation needed]

As evidenced by his commentary throughout the films, White, Time magazine's China correspondent during World War II, was scathing about the People's Republic of China. Remarking that Chinese had been suffering in a 100-year tragedy, he added:

There are 700 millions Chinese [in 1967], one quarter of humane kind, who are taught to hate, their growing power is the world's greatest threat to peace enlightenment. 50 years of torment, bred madness....

For 50 years, Americans have failed to help the Chinese to find "some entry to the modern world", as the Chinese have "been transformed from our greatest friend into our greatest enemy", as the Chinese have fallen into the vicious cycle of "from the tyranny of Confucius of the Manchu Emperor to the tyranny of communism and Mao.

Synopsis

Episode one

White referred to Empress Dowager Cixi as "China's evil spirit... a Manchu concubine... said to have poisoned her own son upon his throne, install her infant nephew as the emperor, killed his mother, and then imprisoned him in 1898."

Episode two

White's impression on the downfall of Qing Dynasty: "...and then it vanished, simply vanished, the Manchu Dynasty disappeared overnight, nothing like that had ever happen in all the history, 2000 years of tradition, the whole structure of the imperial confucianism, political thought, dissolving to dust...."

On post-Qing China, "out of this turbulence, there appeared two types of Asian leaders, arch symbols, the man of gun, and the man of idea, and these two types of gunman and the dreamer, have perplexed all our efforts in Asia for 50 years since, and they still perplexed and haunted all our policy, even today..."

Sun "was a man of dream, the dream of China, powerful, free of emperors and foreigners, made him from his youth a revolutionary.... Slowly from the early 1920, Sun Yatsen had somehow built a government, a tiny southern foothold at Canton, ringed by hostile warlords. By 1924 the ageing revolutionary had learned, idea and gun must go together... in 1923 he tells the New York Times: We have lost hope of help from America, England, France, the only country that show any sign of helping us in the south is the Soviet government of Russia...."

Episode three

The Kuomintang left wing "no longer trust their army leader at the front. Borodin is urging: 'Get rid of Chiang Kai-shek.' In four short years, the communist had grown 60,000 members. To hear the left wing Nationalist: 'No revolution is completed, until peasants own their land, and workers their factories.' Chiang disagreed."

Episode four

"When Mao left at 1927 with a dozen of his ally, it was as if a ghost had risen from the dead, he was disgusted with Borodin and his Russian documents. He felt the key of revolution in Asia lied in the countryside, not the big city proletariat. Mao's idea was simple, turn the hidden peasant's anger towards the local gentry, the local rich.... Mao transformed the countryside into a total environment of hate, women, children, everyone, not to be afraid to die... by 1932, he controlled a good chunk of Hunan, Jiangxi, claimed the loyalty of 9 million people."

Episode five

"Day and night the bombs continue, yet Chiang persists. Powerless to strike back, Chiang knows, only the Americans can help.... It is about this time 1941, at the height of the bombing, I had my first talk with Chiang Kai-shek, about the war with Japan, and strategy. At the end, almost just an afterthought, he said, "remember, Japanese is a disease of the skin, the communists are the disease of the heart." It seems odd to me, because at that time the Japanese were bombing the daylight out of both Chiang Kai-shek and the communist, both of them are ally against the Japanese. And now in retrospect, almost a vision of the apocalypse to come."

Episode six

On Manchuria after the Japanese surrender, "the Russian hed temporarily occupied Manchuria by the surrender term of Japan. Communist expected to get from Russian surrender Japanese equipment and guns, and hold the countryside before Chiang arrived.... Manchuria is the topic of the struggle. Industries Japan had built and left is the greatest pride in China. Chiang's American equipped troops seize all major cities, to find a hollow triumph. The Russian occupiers had rooted every factories before withdrawn, rip out shops and stores where great machines once stood."

Episode seven

"In American custody in Hong Kong there are cascades and piles of translation coming from the Chinese, these are sands, gritty, gravels, little bit of information, meaningless, because we don't know who does what to who in Peking, we don't know how they think, or how they make up their mind, because no matter how hard we study China, we cannot predict such thing as the Great Leap Forward in 1958, we can't predict such thing as Red Guard purge in 1966, as if there was struggle of sea monsters going on, deep deep beneath the surface of our vision, only bubbles come to the surface, to tell us terrible struggle, we don't know what the struggle is about."

Critical reception

While the film won an Emmy Award in the documentary category soon after its release, contemporary critics have criticised his "callous and condescending" portrayal of Chinese. Film Threat remarked that White never attempted to take on board the Chinese viewpoint, and points out there were unconfirmed rumours that the CIA was involved in the film's making.[4][5]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/China:_The_Roots_of_Madness

David Lloyd Wolper (January 11, 1928 – August 10, 2010) was an American television and film producer, responsible for shows such as Roots, The Thorn Birds, and North and South, and the theatrically-released films L.A. Confidential and Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971). He was awarded the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at the 57th Academy Awards in 1985 for his work producing the opening and closing ceremonies of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, as well as helping to bring the games there. His 1971 film (as executive producer) about the study of insects, The Hellstrom Chronicle, won an Academy Award.

Life and career

Wolper was born in New York City, into an eastern European Jewish family, the son of Anna (née Fass) and Irving S. Wolper.[1] He briefly attended Drake University in Des Moines Iowa before transferring to the University of Southern California.[2]

Wolper directed the 1959 documentary The Race for Space, which was nominated for an Academy Award, and others including Biography (1961–63), The Making of the President 1960 (1963) and Four Days in November (1964). Wolper then sold his company to Metromedia for $3.6 million in 1964.[3] In October 1968, he paid $750,000 to leave Metromedia and took six films projects with him.[4] The pre-1968 library is owned by Cube Entertainment (formerly International Creative Exchange), while the post-1970 library (along with Wolper's production company, Wolper Productions, now known as The Wolper Organization[5][6]) has been owned by Warner Bros. since November 1976.[7]

In 1969, Wolper received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[8]

He won an Academy Award for the 1971 film The Hellstrom Chronicle, about the study of insects, which he executive produced. He also produced numerous documentaries and documentary series including The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (TV) (1968), Appointment With Destiny (1971–73 TV series), Visions of Eight (1973), This Is Elvis (1981), Imagine: John Lennon (1988) and others.

On March 13, 1974, one of his crews filming a National Geographic history of Australopithecus at Mammoth Mountain Ski Area was killed when their Sierra Pacific Airlines Corvair 440 slammed into the White Mountains shortly after takeoff from Eastern Sierra Regional Airport in Bishop, California, killing all 35 on board, including 31 Wolper crew members. The filmed segment was recovered in the wreckage and was broadcast in the television series Primal Man. The cause of the crash remains unsolved.[9]

In 1984, he helped bring the Olympic Games to Los Angeles and produced the opening and closing ceremonies.[10] He was awarded the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at the Academy Awards the following year.[10]

In 1988, Wolper was inducted into the Television Hall of Fame.[11] For his work on television, he had received his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Wolper died on August 10, 2010, of congestive heart disease and complications of Parkinson's disease at his Beverly Hills home.[12] He is buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park's Hollywood Hills cemetery.

Productions

His company was involved in the following productions. He was a distributor of the early shows, and became an executive producer with The Race for Space in 1958.[13]

Year Show

1949 Funny Bunnies (36 episodes)

1953 Adventures of Superman (90 episodes)

1954 Baseball Hall of Fame (75 episodes)

1954 O.S.S. (32 episodes)

1954 Grand Ole Opry (39 episodes)

1955 Congressional Investigator (26 episodes)

1958 Men from Boys - The First Eight Weeks

1958 The Race for Space

1959 Project: Man in Space

1960 Hollywood: The Golden Years

1961 Biography of a Rookie: The Willie Davis Story

1961 The Rafer Johnson Story

1962 Hollywood: The Great Stars

1962 Hollywood: The Fabulous Era

1962 D-Day June 6, 1944

1962 Biography

1962–1963 Story of...

1963 Hollywood and the Stars

1963 Escape to Freedom

1963 Kreboizen and Cancer: Thirteen Years of Bitter Conflict

1963 The Passing Years: Rework of Story of a Year 1927

1963 The Making of the President, 1960

1963–1964 Specials for United Artists

1964 The Legend of Marilyn Monroe

1964 The Quest for Peace

1964 A Thousand Days: A Tribute to John Fitzgerald Kennedy

1964 Men in Crisis

1964 Four Days in November

1965 France: Conquest to Liberation

1965 Korea: The 38th Parallel

1965 Prelude to War (Beginning of World War II)

1965 Japan: A New Dawn over Asia (Japan in the 20th Century)

1965 007: The Incredible World of James Bond

1965 Let My People Go: The Story of Israel

1965 October Madness: The World Series

1965 Race for the Moon

1965 Miss Television U.S.A.

1965 The Really Big Family: The Duke of Seattle & Their 18 Children

1965 Revolution in Our Time

1965 The Bold Men

1965 The General

1965 The Teenage Revolution

1965 The Way Out Men

1965 In Search of Man

1965 Pro Football: Mayhem On A Sunday Afternoon

1965 Revolution in the 3 R's

1965 The Thin Blue Line

1965 In Search of Man

1965 Silent Partners

1965–1966 The March of Time

1965–1975 National Geographic Society Specials

1966 The Making of the President, 1964

1966 Wall Street Where the Money Is

1966 A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the White House

1966 Destination Safety

1966 China: Roots of Madness

1966–1968 The World of Animals

1967 The Big Land

1967 A Nation of Immigrants

1967 Untamed World

1967 A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Hollywood

1967 Movin' with Nancy

1967–1968 Do Blondes Have More Fun?

1967–1968 The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau

1968 Rise and Fall of the Third Reich

1968 The Dangerous Years

1968 California

1968 With Love, Sophia

1968 Monte Carlo: C'est La Rose

1968 Sophia: A Self Portrait

1968 The Highlights of the Ice Capades 1968

1968 On the Trail of Stanley and Livingstone

1968 Hollywood: The Selznick Years

1968 The Devil's Brigade

1968 The Making of the President, 1968

1969 The Bridge at Remagen

1969 If It's Tuesday, This Must Be Belgium

1969 Los Angeles: Where It's At

1970 The Unfinished Journey of Robert F. Kennedy

1970 I Love My Wife

1970–1972 The Plimpton Specials

1971 Say Goodbye

1971 They've Killed President Lincoln

1971 The Hellstrom Chronicle

1971 Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory

1971–1973 Appointment With Destiny

1972 King, Queen, Knave

1972 One Is a Lonely Number

1972 Here Comes Tomorrow: The Fear Fighters

1972 Republican Party Films

1972 Make Mine Red, White and Blue

1972 Top of The Month (3 half-hour specials)

1972 Of Thee I Sing

1972–1973 The Explorers

1973 The 500 Pound Jerk

1973 Wattstax

1973 Visions of Eight

1973–1974 Primal Man Specials

1973–1975 The American Heritage Specials

1974 This Week In The NBA (Series of 20 half-hours)

1974 NBA Game of the Week Featurettes

1974 Get Christie Love!

1974 Judgment Specials

1974 The Morning After

1974 Unwed Father

1974 Men of the Dragon

1974 The First Woman President

1974 Love from A to Z

1974 Birds Do It, Bees Do It

1974 The Animal Within

1974 Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus

1974–1975 Get Christie Love!

1974–1975 Smithsonian Specials

1974–1975 Sandburg's Lincoln

1974–1976 Chico and the Man

1975 Death Stalk

1975 I Will Fight No More Forever

1975–1976 Welcome Back, Kotter

1976 Brenda Starr

1976 Collision Course

1976 Celebration: The American Spirit

1976 The Unexplained

1976 Victory At Entebbe

1976 Mysteries of the Great Pyramids

1977 Roots

1978 Roots: One Year Later

1978 The Little Mermaid (Anderusen dowa: Ningyo hime or Andersen Story: The Mermaid Princess)

1978 Roots: The Next Generations

1980 The Man Who Saw Tomorrow

1980 Moviola

1981 This Is Elvis

1981 Hollywood: The Gift of Laughter

1981 Small World

1981 Murder Is Easy

1982 The Mystic Warrior

1982 Casablanca

1983 The Thorn Birds

1984 XXIIIrd Olympiad, Los Angeles 1984

1984 His Mistress

1985 North and South

1986 North and South: Book II

1986 Liberty Weekend

1987 The Betty Ford Story

1987 Napoleon and Josephine: A Love Story

1988 What Price Victory

1988 Imagine: John Lennon

1988 Roots: The Gift

1989 The Plot to Kill Hitler

1989 Murder in Mississippi

1990 Warner Bros. Celebration of Tradition, June 2, 1990

1990 Dillinger

1990 When You Remember Me

1991 Best of the Worst

1991 Bed of Lies

1992 Celebrations

1992 Fatal Deception: Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald

1993 Celebration of a Life: Steven J. Ross Chairman of Time Warner

1993 The Flood: Who Will Save Our Children?

1994 Heaven and Hell: North and South Book III

1994 On Trial

1994 Golf - The Greatest Game

1994 Heroes of the Game

1994 Without Warning

1994 Murder in the First

1995 Prince for a Day

1996 The Thorn Birds: The Missing Years

1996 Surviving Picasso

1997 L.A. Confidential

1998 Terror at the Mall

1998 Warner Bros. 75th Anniversary Show

1998 A Will of Their Own

1998 Confirmation

1998 Legends, Icons and Superstars

1999 To Serve and Protect

1999 Celebrate the Century

See also

Norman Lear

Aaron Spelling

Alan Landsburg

References

"David L. Wolper Biography (1928-)". filmreference.com.

"Emmy award-winning "˜Roots' producer, Drake alum, dies at 82". news.drake.edu/. August 31, 2010.

"METROMEDIA BUYS WOLPER CONCERN; Producer Gets $3.6 Million for Documentary Unit". The New York Times. October 23, 1964. p. 35. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

"Wolper Recovers (At a Price) Indie Status: Plans Two Theatricals Yearly". Variety. January 15, 1969. p. 17.

"Applications Received (Warner Communications Inc.)". Federal Register. October 13, 1976. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

"Permitted (Warner Communications Inc.)". Federal Register. November 26, 1976. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

"Producer David L. Wolper and his company..." Los Angeles Times. July 27, 1988. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

"Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

"'Primal Man' Crash". Check-six.com. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

"Academy Votes Hersholt Award To David Wolper". Daily Variety. February 15, 1985. p. 1.

"Television Hall of Fame Honorees: Complete List".

"David Wolper, producer of 'Roots,' has died". Associated Press. 2010-08-11. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

"Filmography". David L. Wolper. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

External links

Official website

David L. Wolper at IMDb

David L. Wolper at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television Edit this at Wikidata

Works by or about David L. Wolper at Internet Archive

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_L._Wolper

Theodore Harold White (Chinese: 白修德, May 6, 1915 – May 15, 1986) was an American political journalist and historian, known for his reporting from China during World War II and the Making of the President series.

White started his career reporting for Time magazine from wartime China in the 1940s. He was the first foreigner to report on the Chinese famine of 1942–43 and helped to draw international attention to the shortcomings of the Nationalist government.

After leaving Time, he reported on post-war Europe for popular magazines in the early 1950s, but lost these assignments because of his association with the "Loss of China". He regained national recognition with The Making of the President 1960, whose combination of interviews, on the ground reporting, and vivid writing were developed in best-selling accounts of the 1964, 1968, 1972, and 1980 presidential elections, and became a model for later journalists.

Early life

White was born May 6, 1915, in Dorchester, Boston. His father, David White, was a lawyer. He was raised Jewish, and as a teenager was a member of the socialist-Zionist Hashomer Hatzair youth movement. He was a scholarship student at Boston Latin School, from which he graduated in 1932; from there, he went on to Harvard College, from which he graduated with a B.A. in history as a student of John K. Fairbank, who went on to become a leading China scholar and White's longtime friend. In his memoir In Search of History: A Personal Adventure, White describes helping form one of the early Zionist collegiate organizations.[1] He also wrote for The Harvard Crimson.[2]

China

Awarded a Harvard traveling fellowship for a round-the-world journey, White ended up in Chungking (Chongqing), China's wartime capital. The only job he could find was with China's Ministry of Information. When Henry R. Luce, the China-born founder and publisher of Time magazine, came to China, he learned of White's expertise, the two bonded, and White became the China correspondent for Time during the war. He was the first foreign journalist to report the widespread Henan Famine and he filed stories on the strength of the Chinese Communists.

White chafed at the restrictions put on his reporting by the Chinese government censorship, but he also chafed at the spiking or rewriting of his stories by the editors at Time, one of whom was Whittaker Chambers.[3]

Although he maintained respect for Luce, White resigned and returned home to write freely, along with Annalee Jacoby, widow of fellow China reporter, Mel Jacoby. Their book about China at war and in crisis was the best-selling Thunder Out of China. The book described the incompetence and corruption of the Nationalist government and sketched the power of the rising Chinese Communist Party.

The introduction warned, "In Asia there are a billion people who are tired of the world as it is; they live such terrible bondage that they have nothing to lose but their chains.... Less than a thousand years ago Europe lived this way; then Europe revolted... The people of Asia are going through the same process." [4]

White also witnessed and reported on the famine that occurred in Henan in 1943.[5] White then served as European correspondent for the Overseas News Agency (1948–50) and for The Reporter (1950–53).[citation needed]

He returned to his wartime experience in the novel The Mountain Road (1958), which dealt with the retreat of a team of American troops in China in the face of a Japanese offensive provoked by bombings by the 14th Air Force. The novel was frank about the Americans' conflicting, sometimes negative attitudes toward their allies. It was made into a 1960 movie.[citation needed]

The McCarthy period made it difficult for any reporter or official who had had any contact with communists, however innocent, to escape suspicion of communist sympathies. White opted to turn from writing about China to take up reporting on the Marshall Plan in Europe and then ultimately to the American presidency.[citation needed]

Making of the President series

With experience in analyzing foreign cultures from his time abroad, White took up the challenge of analyzing American culture with the books The Making of the President 1960 (1961), The Making of the President 1964 (1965), The Making of the President 1968 (1969), and The Making of the President 1972 (1973), all analyzing United States presidential elections. The first of these was both a bestseller and a critical success, winning the 1962 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction.[6] It remains the most influential publication about the 1960 presidential election that made John F. Kennedy the President. The later presidential books sold well but failed to have as great an effect, partly because other authors were by then publishing about the same topics, and White's larger-than-life style of storytelling became less fashionable during the 1960s and '70s.

A week after the death of JFK, Jacqueline Kennedy summoned White to the Kennedy Compound in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, to rescue her husband's legacy. She proposed that White prepare an article for Life magazine drawing a parallel between her husband and his administration to King Arthur and the mythical Camelot. At the time, a play of that name was being performed on Broadway and Jackie focused on the ending lyrics of an Alan Jay Lerner song, "Don't let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment that was known as Camelot." White, who had known the Kennedy family from his time as a classmate of the late President's brother, Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., was happy to oblige. He heeded some of Jackie's suggestions while writing a 1,000-word essay that he dictated later that evening to his editors at Life. When they complained that the Camelot theme was overdone, Jackie objected to changes. By this telling, Kennedy's time in office was transformed into a modern-day Camelot that represented, "a magic moment in American history, when gallant men danced with beautiful women, when great deeds were done, when artists, writers, and poets met at the White House, and the barbarians beyond the walls held back." White later described his comparison of JFK to Camelot as the result of kindness to a distraught widow of a just-assassinated leader, and wrote that his essay was a "misreading of history. The magic Camelot of John F. Kennedy never existed."[7]

White also interviewed Kennedy's rival Richard Nixon, analyzing his victories in the 1968 and 1972 presidential elections. White interpreted Nixon's victories as a popular rejection of the U.S. welfare state created by the New Deal and the Great Society. He predicted that Nixon would emerge alongside Franklin D. Roosevelt as one of the greatest U.S. Presidents of the 20th century.[8] After Watergate and the fall of Nixon, White broke his quadrennial pattern with Breach of Faith: The Fall of Richard Nixon (1975), a dispassionate account of the scandal and its players. There was no 1976 volume from White; the closest analogue was Marathon by Jules Witcover. After a volume of memoirs, published in 1978, he returned to presidential coverage with the 1980 campaign, and America in Search of Itself: The Making of the President 1956–80 (1982), draws together original reporting and new social analysis of the previous quarter-century, focusing primarily but not exclusively on the Reagan-Carter contest.

TIME partnered with White to publish the 400 page The Making of the President 1984, which was to be a collaborative effort amongst multiple writers. White was expected to write the opening and closing chapters, and the chapter covering the 1984 Democratic National Convention. The remaining chapters were to be written by other Time magazine writers, principally Hays Gorey, Time's Washington correspondent. However, prior to the election, the partnership dissolved, as White was unhappy with the quality of work he was seeing from the Time reporters.[9] This final entry in the series was shortened and titled "The Shaping of the Presidency, 1984," a lengthy post-election analysis piece in Time, in its special Ronald Reagan issue of November 19, 1984.

Personal life and death

White's marriage to Nancy Bean ended in divorce.[1] They had a son and a daughter, Heyden White Rostow and David Fairbank White. His second marriage was to Beatrice Kevitt Hofstadter, the widow of historian Richard Hofstadter.

On May 15, 1986, nine days after his 71st birthday, White suffered a sudden stroke and died in New York City. He was survived by his children and his wife.[10]

Assessments

Both W. A. Swanberg in Luce and His Empire and David Halberstam in The Powers That Be discuss how White's China reporting for Time was extensively rewritten, frequently by Whittaker Chambers, to conform to publisher Henry Luce's admiration for Chiang Kai-shek. Chambers himself explained:

The fight in Foreign News was not a fight for control of a seven-page section of a newsmagazine. It was a struggle to decide whether a million Americans more or less were going to be given the facts about Soviet aggression, or whether those facts were going to be suppressed, distorted, sugared or perverted into the exact opposite of their true meaning. In retrospect, it can be seen that this critical struggle was, on a small scale, an opening round of the Hiss Case.[11]

Conservative author William F. Buckley, Jr. wrote an obituary of White in the National Review, saying that "conjoined with his fine mind, his artist's talent, his prodigious curiosity, there was a transcendent wholesomeness, a genuine affection for the best in humankind." He praised White, saying he "revolutionized the art of political reporting." Buckley added that White made one grave strategic mistake during his journalistic lifetime: "Like so many disgusted with Chiang Kai-shek, he imputed to the opposition to Chiang thaumaturgical social and political powers. He overrated the revolutionists' ideals, and underrated their capacity for totalitarian sadism."[12][13]

In her book, Theodore H. White and Journalism As Illusion, Joyce Hoffman contends that White's "personal ideology undermined professional objectivity" (according to the review of her work in Library Journal). She states "conscious mythmaking" on behalf of his subjects, including Chiang Kai-shek, John F. Kennedy, and David Bruce. Hoffman concludes that White self-censored information embarrassing to his subjects to portray them as heroes.

Others note that White and Jacoby reported on but did not endorse Chinese Communist strength, [14] and cite such passages as:

Will the Communists, if they govern large and complex industrial cities, permit an opposition press and opposition party to challenge them by a combination of patronage and ideology? .... But if the Communists are wrong in their calculations and are outvoted, will they yield to a peaceful vote? Will they champion civil liberties as ardently as they do now? This is a question that cannot be answered until we have had the opportunity of seeing how a transitional coalition regime works in peace time practice. [15]

They also note that the book's influence was ephemeral.[16] Henry Luce, however, refused to even tip his hat to White when they passed on the street, and bitterly criticized "that book by that ugly little Jewish son of a bitch."[17]

Contemporary critics on the left have strongly criticized a 1967 made-for-TV documentary that White wrote called China: The Roots of Madness as a "callous and condescending" portrayal of Chinese. White's reporting was described as "self-important, sanctimonious and he gave voice to no more than an American viewpoint", wherein he portrayed the Chinese as merely pawns in the Cold War, blinkered by their Communist ideology. Film Threat remarked that White never attempted to take on board the Chinese viewpoint, and points out there were unconfirmed rumors that the Central Intelligence Agency was involved in the film's making.[18][19]

Portrayal

His reporting role in Henan is portrayed by actor Adrien Brody in the 2012 film Back to 1942. Billy Crudup portrayed "the Journalist", an unnamed representation of White, in Pablo Larraín's Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis biopic Jackie.

Selected publications

White, Theodore H.; Jacoby, Annalee (1946). Thunder Out of China. New York: Sloane. Reprinted: Da Capo, 1980, ISBN 0306801280.

The Stilwell Papers (1948) by Joseph W. Stilwell, Theodore H. White (ed.)

Fire in the Ashes: Europe in Mid Century (1953)

The Mountain Road (1958), novel, reprinted with an introduction by Parks Coble, Eastbridge, 2006, ISBN 978-1-59988-000-6, which was made into a movie starring James Stewart.

The View from the Fortieth Floor (1960). Novel, depicted his experience at Colliers.

The Making of the President 1960 (1961)

The Making of the President 1964 (1965)

The Making of the President 1968 (1969)

Caesar at the Rubicon: A Play About Politics (1968)

The Making of the President 1972 (1973)

Breach of Faith: The Fall of Richard Nixon. Atheneum Publishers, 1975; Dell, 1986, ISBN 978-0-440-30780-8. OCLC 1370091. A history of the Watergate Scandal, Richard Nixon, and key players of the events.

——— (1978). In Search of History: A Personal Adventure. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0060145994.. Memoir of White's early years, training at Harvard under John K. Fairbank, experiences in wartime China, relations with Time publisher Henry Luce, and later tribulations and success as originator of the Making of the President series.

America in Search of Itself: The Making of the President 1956–1980 (Harper & Row, 1982) ISBN 978-0-06-039007-5

Theodore H. White at Large: The Best of His Magazine Writing, 1939–1986, Theodore Harold White, ed. Edward T. Thompson, Pantheon Books, 1992, ISBN 978-0-679-41635-7

Notes

White (1978).

Bethell, John T.; Hunt, Richard M.; Shenton, Robert (2004). Harvard A to Z. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 183. ISBN 0-674-01288-7. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

Hayford (2009), pp. 304–306.

WhiteJacoby (1946), p. 20.

White, Theodore Harold.(1943). Until the Harvest Is Reaped,Time, March 22, 1943, pg. 19

"The Making of the President 1960, by Theodore H. White (Atheneum)". Pulitzer. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

White (1978), p. 524.

Dobbs, Michael (2021). King Richard: Nixon and Watergate: An American Tragedy (1 ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 121–124. ISBN 978-0-385-35009-9. OCLC 1176325912.

"Theodore White-Time Book Project Dissolves", The New York Times, October 4, 1984

Obituary of Beatrice Kevitt Hofstadter, New York Times, November 1, 2012.

Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. New York: Random House. p. 498. ISBN 978-0-89526-571-5.

Buckley, William F. Jr. (May 22, 1986), National Review {{citation}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

Buckley, William F. Jr.; Kimball, Roger & Bridges, Linda (2010), Athwart History: Half a Century of Polemics, Animadversions, and Illuminations: A William F. Buckley Jr. Omnibus, Encounter Books, p. 315, ISBN 978-1-59403-379-7

Hayford (2009), p. 306.

Theodore White, Annalee Jacoby,Thunder Out of China, pp 236-237

Hayford (2009), p. 307.

White, In Search of History, p. 254-57

"China: The Roots of Madness, 1967: Movies & TV", Amazon.com, Retrieved March 25, 2011

"The Bootleg Files: China: The Roots Of Madness", Film Threat, June 11, 2010. Retrieved March 25, 2011

References and further reading

Brands, Hal (2010), "(Review Article) Burying Theodore White: Recent Accounts of the 1960 Presidential Election", Presidential Studies Quarterly, 40 (2): 364–367, doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2010.03761.x, JSTOR 23044826

Ferling, John E. "History as Journalism: An Assessment of Theodore White." Journalism Quarterly 54.2 (1977): 320-326.

French, Paul. Through the Looking Glass: Foreign Journalists in China, from the Opium Wars to Mao. Hong Kong University Press, 2009.

Griffith, Thomas. Harry and Teddy: The Turbulent Friendship of Press Lord Henry R. Luce and His Favorite Reporter, Theodore H. White. New York: Random House, 1995.

Hayford, Charles W. (2009). "China by the Book: China Hands and China Stories, 1848-1948". Journal of American-East Asian Relations. 16 (4): 285–311. doi:10.1163/187656109792655508.

Hoffmann, Joyce. Theodore H. White and journalism as illusion (U of Missouri Press, 1995).

Rand, Peter. China Hands. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Sullivan, Walter. ". . . The Crucial 1940s Nieman Reports." The Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University (Spring 1983) [1]

External links

Papers of T. H. White: an inventory (Harvard University Archives). Includes a biographical notice.

Theodore H. White

Theodore White - JFK Presidential Library & Museum

Theodore H. White at IMDb

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_H._White

William T. "Bill" Cartwright Sr. (born August 25, 1920 St. Louis, Missouri; died June 1, 2013 North Hills, California)[1] was an American television and film director, producer and editor responsible for a number of documentaries. He was nominated for 5 Emmys Emmy Awards in 1978 and 1997 and won three. He edited "Maya Lin: A Strong Clear Vision" which won an Oscar. He also has many credits for direction and producing. His son William T. Cartwright Jr. is also an editor and is credited with some of the titles listed below.

Cartwright was also known for helping save the Watts Towers in association with Nicholas King.

Cartwright died in hospice care on June 1, 2013. He was 92.

Filmography

Man Ray: Prophet of the Avant Garde (1997) (TV)

Don't Pave Main Street: Carmel's Heritage (1994)

Maya Lin: A Strong Clear Vision (1994)

Oscar Presents: The War Movies and John Wayne (1977) (TV)

It Was a Very Good Year (1971) TV Series

The Bridge at Remagen (1969)

The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1968)

The Devil's Brigade (1968)

China: Roots of Madness (1966) (TV)

Time-Life Specials: The March of Time (1965) (TV)

Four Days in November (1964)

The Making of the President 1960 (1963) (TV)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Cartwright_(film_editor)

Ernest Batson Price (October 13, 1890 – October 20, 1973) was an American diplomat, university professor, military officer, and businessman. He spent over twenty years in China and witnessed first-hand warlord power struggles, the growth of Japanese militarism, America's post-war diplomacy, China's civil war, and the profound social change that followed. As a result of this first-hand experience, Price was one of America's foremost authorities on Chinese language, culture, and politics from the early nineteen twenties through the mid nineteen fifties.

Early life

Price was the son of Baptist missionaries serving in Henzada, Burma. He was born on October 13, 1890, the youngest of four children. After his father died in 1899, he was sent to school at Wayland Academy in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin. After high school, he taught in a small, rural school in a German-speaking community in North Dakota. While there, he learned to speak, read and write German. His fluent German helped him get into college, and later qualified him to compete for an appointment in the United States Foreign Service. He attended college at University of Rochester in Rochester, New York, graduating in 1913.[1][2]

Foreign service

After graduation, Price was accepted into the special China branch of the Foreign Service, and posted to China. Upon arrival, he began intensive study of Mandarin, China's official language, with a traditional Chinese scholar. In less than two years he was fluent in Mandarin, and was posted to Tientsin as vice consul.[3]

He had met Florence Mary Bentley when he was studying at Rochester. Since state-side leave was not authorized for junior diplomats, he arranged an administrative trip to Yokohama, Japan in 1915. Florence joined him there, and they were married. The Prices spent the next 15 years in China where all five of their children were born.[4]

In China, personal friendships were critical, and Price had many influential friends throughout China. He eventually got to know numerous warlords, and dealt with them on a personal basis as he tried to expand American trade without taking sides in China's internal power struggles. The personal relationships that Price built with powerful Chinese leaders provided an important counterbalance to Imperial Japan's growing military presence in China and the influence of Comintern agents like Mikhail Borodin.[5]

In Canton, Price met Doctor Sun Yat-sen, who later became the first President of the Republic of China. They became good friends and often discussed politics over the bridge table. Their friendship continued even after Price was reassigned to Fuzhou where he served as United States consul.[3][4] Sun Yat-sen personally invited both Price and his wife to his inauguration ceremony staged by the Nationalist government. The United States did not recognize the Nationalist government, choosing instead to retain official ties with the rival government in Peking. Therefore, Price could not attend a Nationalist-sponsored ceremony. Mrs. Price, however, was not a Government official so she did attend, and her detailed report of the event was passed to the United States Department of State in a formal dispatch.[4]

In 1920, when he was Assistant Chinese Secretary in the American Legation in Peking, Price was assigned to escort an American trading company's caravan of Model-T Fords from the Chinese border, across the Gobi desert to Urga, Mongolia (now Ulan Bator). While he was responsible for negotiating passage for the American businessmen though the territory of various Chinese warlords, Price was also charged with a secret mission of contacting the United States consul in Irkutsk, Russia. Due to the chaos in Siberia caused by the Bolshevik revolution and the subsequent civil war in Russia, the American consul had not been heard from in many months.[3][4] Price was successful in both tasks, and returned to China in the company of Roy Chapman Andrews, the well known archeologist and adventurer who is often cited as the inspiration for Indiana Jones. Andrews recounted the journey in this book Across Mongolian Plain.[6] Here is how Andrews recalled one of their travel adventures:

Price and I drove back to Panj-kiang to obtain extra food and water ... We had gone only five miles when we discovered that there was no more oil for our motor ... Just then the car swung over the summit of a raise, and we saw the white tents and grazing camels of an enormous caravan. Of course, Mongols would have mutton fat and why not use that for oil! The caravan leader assured us that he had fat in plenty and in ten minutes a great pot of it was warming over the fire. We poured it into the motor and proceeded merrily on our way.[6]

Andrews also incorporated the true story of Price's hunt for a man-eating tiger in the mountains of southern China into his adventure novel Quest of the Snow Leopard.[7]

In 1928, Price was sent to re-open the United States consulate in Nanjing.[4] On 1 June 1929, Price and his wife attended the state burial ceremony for Sun Yat-sen at the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum near Nanjing. They were special guests of the Chinese government along with John Van Antwerp MacMurray, the United States Minister to China.[8][9][10]

Price continued to serve in diplomatic posts throughout China until late 1929 when he left the Foreign Service to become President of China Airways (now China National Aviation Corporation, parent company of Air China), a post he held for two years before returning to the United States to pursue a doctoral degree.[2]

Academic career

Before beginning his doctoral studies at Johns Hopkins University, Price worked as a Special Assistant to the President of the University of Oregon. While there, he began a lifelong friendship with a young law professor named Wayne Morse whom Oregonians later elected to four terms in the United States Senate.

Johns Hopkins awarded Price a PhD in political science in 1933,[2] and published his book, The Russo-Japanese Treaties of 1907-1916 Concerning Manchuria and Mongolia that same year. The book chronicled the remorseless efforts of Japan and Russia to carve up northeast Asia.[11] In 1935, Price visited Manchukuo, Japan's puppet state in Northeast China, and met with the last Manchu emperor, Pu Yi. His book along with a number of academic articles published in the mid-nineteen thirties when he was a fellow at the Brookings Institution highlighted the threat of Japanese imperialism in Manchuria and China. Price warned that Japan's aggressive policies could lead to a serious international conflict.[12][13][14][15] His writing helped initiate the public debate over the "China question" in the years leading up to World War II. His warnings proved to be both prophetic and timely.

In 1936, Doctor Price became director of International House at the University of Chicago. Price spoke three European languages and at least three varieties of Chinese, so he was well suited to host the many distinguished foreign visitors who passed through International House. He also taught Chinese studies in the university's political science department.[16]

World War II

During the early days of World War II, Price was associated with the Office of Strategic Services (forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency).[3][17] Price's analysis of the war in China and related United States policy options were passed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt either through Major General William Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services, or in some cases, directly to the President.[18] In 1944, he was released for duty with the United States Marine Corps,[2] and commissioned as a Captain to begin planning for an allied invasion of Japanese occupied China. However, he also maintained ties with the Office of Strategic Services until it was disbanded in 1945.[19]

Price announcing Japanese surrender in China

After the atomic bomb was dropped on Japan in August 1945, Price was immediately dispatched to China, and landed with the first wave of American occupation troops. He was assigned as the civil affairs liaison officer on the personal staff of Major General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., commander of the 6th Marine Division. Price was present for the formal surrender of Japanese forces in China on October 25, 1945, and made the first Chinese-language radio announcement of the surrender. In February 1946, he received a Bronze Star medal for his "sound advice based on a thorough understanding of the Chinese people and of the civil affairs associated with the occupation of an area in which political and civil government problems were most complex."[20]

Following the war, Price remained in China to support the United States ambassador, General Patrick Hurley, and later General George C. Marshall as they tried to negotiate a coalition government that would prevent a bloody civil war between Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist forces and Mao Zedong's communists. Both negotiation efforts ultimately failed; however, General Marshall awarded Price a second Bronze Star for his support. The award cited his "keen sense of judgment particularly with regard to the diplomatic behavior demanded while acting in the capacity of liaison officer between high ranking Chinese officials and United States forces."[21]

Post-war career

Price returned to the United States and was released from active duty in April 1946. However, he remained an officer in the Marine Corps reserve until 1954, ending his military career as a reserve Major.

Shortly after leaving active duty, Doctor Price accepted a position with Standard Vacuum Oil Company (now part of ExxonMobil). It was the company's intent to expand their oil exploration work into China when the political situation there stabilized. Price became the company's agent in Hong Kong and then Shanghai. He continued working there until the communist revolution forced the company to withdraw from mainland China. Price stayed with the company until he finally retired in 1960. He died on October 20, 1973 in Los Gatos, California.[1][2]

Achievements

Doctor Price's diplomatic dispatches, journals, correspondence, speeches, lecture material, and other papers are now in the Hoover Institute archives at Stanford University. A detailed catalog of the archived materials has been compiled by the Institute staff and is available on-line through the California Digital Library. His book, The Russo-Japanese Treaties of 1907-1916 Concerning Manchuria and Mongolia is still available in the reference section of many public policy libraries including the National Defense University library at Fort McNair in Washington, D.C.[2]

References

"Dr. Ernest B. Price" San Francisco Chronicle, 22 October 1973

"Register of the Ernest Batson Price Papers, 1914-1960", Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University, Stanford, California, 11 November 2010.

Illingworth, Hal, "Former U. S. Consul in China", Leisure World News, Laguna Hills, California, 27 January 1966, p. 20.

Price, Ernest B., Your Obedient Servant, unpublished manuscript: 1942

White, Theodor H., China the Roots of Madness, Norton & Company, New York: 1968

Andrews, Roy Chapman, Across Mongolian Plains, Appleton & Company, New York: 1921

Andrews, Roy Chapman, Quest of the Snow Leopard, Viking Press, New York: 1957

Official Publication commemorating the State Burial of the late Dr. Sun Yat-sen, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, National Government of the Republic of China, Nanjing, China, 1 June 1929.

Bergere, Marie-Claire (translated from French to English by Janet Llyod), Sun Yat-sen, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, 1998, pp. 411-412.

"Trip to attend the reinterment of Sun Yat-sen, 1929", Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, posted 3 August 2010, accessed 289 December 2015.

Price, Ernest B., The Russo-Japanese Treaties of 1907-1916 Concerning Manchuria and Mongolia, Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore: 1933

Peffer, Nathaniel, "A Biography of the Manchurian Crisis," New York Herald-Tribune, 27 August 1933

"The Asiatic Problem," Boston Evening Transcript, 19 July 1933

Story, Russell, book review, The Annals, American Academy of Political and Social Science, Philadelphia: September 1934, p. 250

Price, Ernest B., "The Manchurians and Their New Deal," Pacific Affairs, June 1935

Foss, Theodore N., “Chinese Studies at Chicago—A Brief History of the Origin of Chinese Studies at the University of Chicago” Archived 2008-09-05 at the Wayback Machine, Tableau, University of Chicago: Spring/Summer 2007, p.5.

Yu, Maochun, OSS in China Prelude to the Cold War, Yale Press, New Haven: 1996

President Franklin Roosevelt's Office Files, 1933–1945, Part 1: "Safe" and Confidential Files, (General Editor: William E. Leuchtenburg); file number 0397, Office of Strategic Services, activities in China (Feb 1942-Apr 1944)

Office of Strategic Services honorable service certificate signed by Major General William Donovan, U.S. Army, 1 October 1945

Bronze Star Medal citation, signed by Major General A. F. Howard, U.S. Marine Corps, 19 January 1946

Bronze Star Medal citation, awarded by the Commanding General, U.S. Army Forces, China, forwarded through General A. A. Vandegrift, Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps, 14 October 1946

External links

California Digital Library

Hoover Institute

Online Archives of California - Ernest B. Price

Authority control Edit this at Wikidata

International

ISNI VIAF WorldCat

National

France BnF data Germany Israel United States

Other

SNAC IdRef

Categories:

1890 births1973 deaths20th-century American businesspeopleAmerican diplomatsUniversity of Chicago facultyUnited States Marine Corps personnel of World War IIPeople from Ayeyarwady RegionUnited States Marine Corps officersPeople of the Office of Strategic ServicesWayland Academy, Wisconsin alumni

-

45:29

45:29

The Memory Hole

1 month agoHow a Washington Assassination Brought Pinochet's Terror State to Justice (2019)

7382 -

20:53

20:53

SLS - Street League Skateboarding

2 days agoGold Medals, World Class Food, Night life & more - Get Lost: Tokyo

12.5K4 -

47:13

47:13

PMG

18 hours ago"Hannah Faulkner and Doug Billings | WHY LIBERALS LOST THE ELECTION"

1.21K -

59:01

59:01

The Liberty Lobbyist

4 hours ago"We Only Have NOW To Make a Difference"

9.97K2 -

4:16:41

4:16:41

CatboyKami

5 hours agoStalker 2 Blind playthrough pt1

6.7K2 -

1:06:27

1:06:27

Russell Brand

5 hours agoNeil Oliver on the Rise of Independent Media, Cultural Awakening & Fighting Centralized Power –SF498

171K259 -

1:39:14

1:39:14

vivafrei

5 hours agoSoros Karma in New York! Tammy Duckwarth Spreads LIES About Tulsi Gabbard! Pennsylvania FLIPS & MORE

80.1K64 -

1:57:36

1:57:36

The Charlie Kirk Show

5 hours agoInside the Transition + The Bathroom Battle + Ban Pharma Ads? | Rep. Mace, Tucker, Carr | 11.21.24

129K53 -

59:20

59:20

The Dan Bongino Show

8 hours agoBitter CNN Goes After Me (Ep. 2375) - 11/21/2024

850K3.58K -

57:28

57:28

TheMonicaCrowleyPodcast

3 hours agoThe Monica Crowley Podcast: Mandate into Action

16K2