Premium Only Content

U.S. Government Run Human and Sex Trafficking & Enslavement of All Women & Races

Governments lie; this comes as a surprise to nobody. But governments can’t lie, nor can they tell the truth. Governments don’t speak at all. People speak. And depending on their role in government, and their purpose, and their audience, the terrain of the lies they tell is vast. It ranges from a manager in a state agency writing malicious lies about a former employee in a job reference, to a diplomat dissembling to another government, to the years of lies about “progress” in the Vietnam War coming from the upper reaches of the defense establishment and documented in the Pentagon Papers.

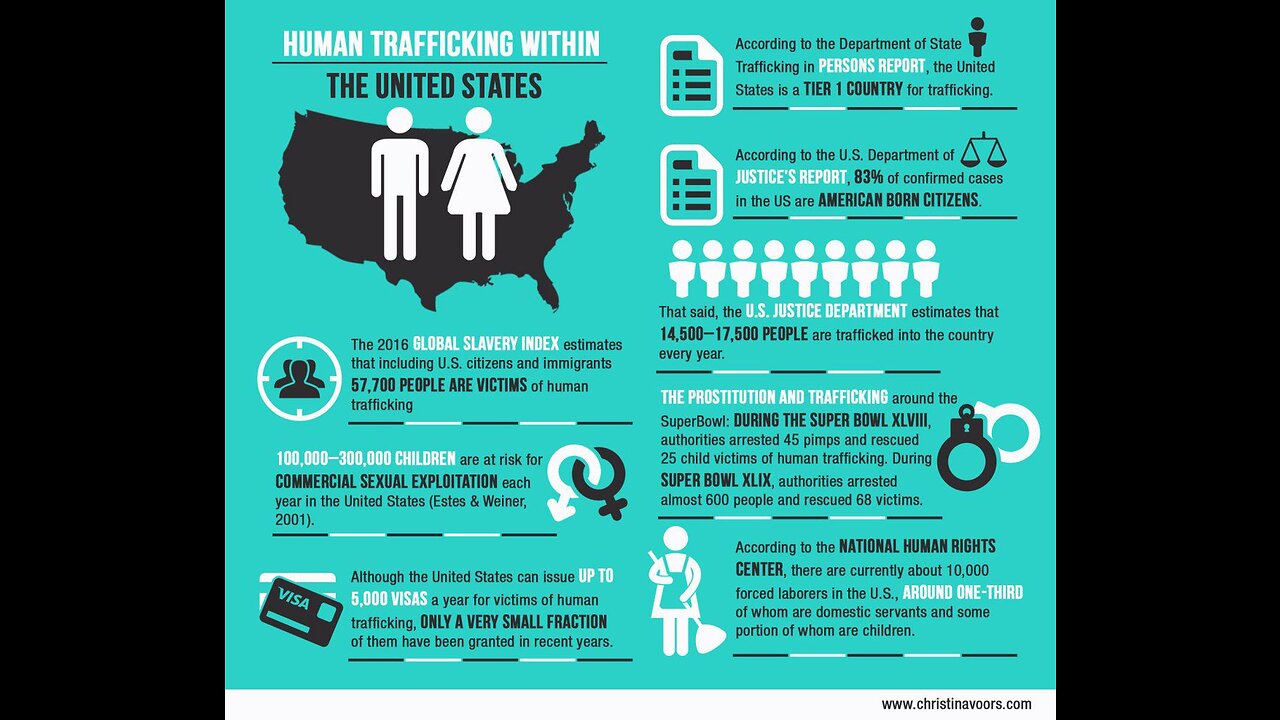

United States, the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000, as amended, provides the tools to combat trafficking in persons both worldwide and domestically. The Act authorized the establishment of the State Department’s TIP Office and the President’s Interagency Task Force to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons to assist in the coordination of U.S. government anti-trafficking efforts. Internationally, several conventions, in particular the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (Palermo Protocol), set out international standards for combating trafficking in persons. Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000, as amended, provides the tools to combat trafficking in persons both worldwide and domestically. The Act authorized the establishment of the State Department’s TIP Office and the President’s Interagency Task Force to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons to assist in the coordination of anti-trafficking efforts.

Human trafficking is a global crime that trades in people of all genders, ages and backgrounds and exploits them for profit. Human trafficking generally takes two forms: sex trafficking in which a commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not attained 18 years of age; or the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage or slavery.

Human traffickers prey on people who are hoping for a better life, lack employment opportunities, have an unstable home life or have a history of sexual or physical abuse. Traffickers promise a high-paying job, a loving relationship or new and exciting opportunities and then use physical and psychological violence to control them.

A wide range of criminals, including individuals, family operations, small businesses, loose-knit decentralized criminal networks and international organized criminal operations, can be human traffickers. Often the traffickers and their victims share the same national, ethnic or cultural background, allowing the trafficker to better understand and exploit the vulnerabilities of their victims. Traffickers can be foreign nationals and U.S. citizens, males and females, family members, intimate partners, acquaintances and strangers.

Due to the complex nature of the crime, traffickers often operate under the radar, and those trafficked are not likely to identify as victims, often blaming themselves for their situation. This makes it more difficult to identify the crime because victims rarely report their situation. Often victims are misidentified and treated as criminals or undocumented migrants. In some cases, they are hidden behind doors as domestic help in a home. In other cases, victims live in plain sight and interact with people daily, yet they experience commercial sexual exploitation or forced labor under extreme circumstances in public settings such as exotic dance clubs, factories or restaurants and are not identified due to a lack of identification training and awareness.

What makes it a policy lie is that torture was his government’s policy, and nearly every high official had signed off on it: the vice president, the secretaries of defense and state, the national security advisor, the CIA director, the attorney general, and all their lawyers. The fictitious Tonkin Gulf Incident, used to get Congress to approve the Vietnam War without declaring war, was a policy lie. So were the massive falsehoods detailed in the Pentagon Papers, to perpetuate a war that had lost all purpose except to maintain the mirage of “credibility” that fooled no one. And so were the “fixed” intelligence findings used to justify the Iraq War. It may be that some U.S. officials, like Colin Powell and perhaps Bush himself, actually believed that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction.

This tendency to lie pervades all police work, not just high-profile violence, and it has the power to ruin lives. Law enforcement officers lie so frequently—in affidavits, on post-incident paperwork, on the witness stand—that officers have coined a word for it: testilying. Judges and juries generally trust police officers, especially in the absence of footage disproving their testimony. As courts reopen and convene juries, many of the same officers now confronting protesters in the street will get back on the stand.

Defense attorneys around the country believe the practice is ubiquitous; while that belief might seem self-serving, it is borne out by footage captured on smartphones and surveillance cameras. Yet those best positioned to crack down on testilying, police chiefs and prosecutors, have done little or nothing to stop it in most of the country. Prosecutors rely on officer testimony, true or not, to secure convictions, and merely acknowledging the problem would require the government to admit that there is almost never real punishment for police perjury.

Officers have a litany of incentives to lie, but there are two especially powerful motivators. First, most evidence obtained from an illegal search may not be used against the defendant at trial under the Fourth Amendment’s exclusionary rule; thus, officers routinely provide false justifications for searching or arresting a civilian. Second, when police break the law, they can (in theory) suffer real consequences, including suspension, dismissal, and civil lawsuits. In many notorious testilying cases, including Parham’s, officers blame the victim for their own violent behavior in a bid to justify disproportionate use of force. And departments will reward officers whose arrests lead to convictions with promotions.

To end testilying, Levine said, “I would entirely change incentive structures.” Officers would be rewarded for reporting on their colleagues’ lies and scrutinized when their stories do not line up. They would no longer be able to coordinate their stories before testifying, a common procedure that lets them iron out potential inconsistencies. Nor could they watch bodycam footage before providing their version of events, another perk that’s not provided to civilians. Prosecutors would be rewarded for rooting out unconstitutional behavior. Officers who lie, and prosecutors who tolerate them, would be terminated immediately. In short, the system would encourage police officers and prosecutors to focus less on winning cases and more on following the rules, even when a constitutional violation stands in the way of a conviction.

What would happen if a city really tried to eliminate testilying? I posed this question to Bennett Capers, a former federal prosecutor and Fordham Law professor who studies police lies. “In all honesty, I think my initial reaction would be that the system cannot exist without it,” he told me. “It would grind to a halt.” Capers said that “run of the mill policing would have to change. We are doing about 13 million misdemeanor arrests a year. With a lot of those small crimes, there’s fudging. Nobody’s paying attention.”

Police, in other words, would have to stop arresting so many people for minor crimes. Once cities stopped deploying officers to harass misdemeanants, they could shrink their police force, reducing the number of encounters between cops and civilians. Agencies might then dedicate those resources to investigative and detective work in order to build solid cases against suspects, thereby creating a higher bar for which cases to pursue. Prosecutors would be forced to make a more careful calculation about the risk of bringing a case to trial and drop cases that rested on a search of dubious legality. In the short term, the legitimacy of the entire system might take a hit—though only because its participants confronted the illegitimate basis of so many convictions. Over time, however, the system might regain the legitimacy it lost with a preference for punishment over justice.

“We all wanted to see justice happen,” Capers recalled from his time as a prosecutor. “And law enforcement often thinks that, in the interest of justice, the rules get in the way. I’m not aware of ever saying, ‘Does this story sound quite right?’ We benefited from small lies.”

-

4:48

4:48

What If Everything You Were Taught Was A Lie?

24 days agoOpen Your Mind Wow... So Old Sayings Do Truly Have Meaning And An True Origin Story

4.17K4 -

1:11:10

1:11:10

Steve-O's Wild Ride! Podcast

5 days ago $8.70 earnedDusty Slay Went From Selling Pesticides To Having A Netflix Special - Wild Ride #244

27K3 -

1:16:02

1:16:02

CocktailsConsoles

5 hours agoBE PART OF THE GAME!!| Death Road to Canada | Cocktails & Consoles Livestream

19K1 -

LIVE

LIVE

Phyxicx

7 hours agoWe're streaming again! - 11/26/2024

205 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

GamingWithHemp

6 hours agoHanging with Hemp #103

1,364 watching -

21:24

21:24

DeVory Darkins

1 day ago $10.23 earnedElon Musk and Tucker Carlson SHATTER Left Wing Media

36.5K36 -

15:13

15:13

Stephen Gardner

4 hours ago🔥Breaking: Trump JUST DID the UNEXPECTED | Tucker Carlson WARNS America!

31.6K71 -

1:18:01

1:18:01

Glenn Greenwald

9 hours agoWill Trump's Second Term Promote Economic Populism? Matt Stoller On Cabinet Picks To Fight Corporate Power; Should Liberals Cut Off Pro-Trump Friends & Family? | SYSTEM UPDATE #372

172K187 -

2:26:30

2:26:30

WeAreChange

9 hours agoTrump To Subdue Deranged Opposition! ARRESTS Planned

134K52 -

1:19:04

1:19:04

JustPearlyThings

10 hours agoWhy MODERN WOMEN Keep REJECTING The Redpill! | Pearl Daily

103K55