Premium Only Content

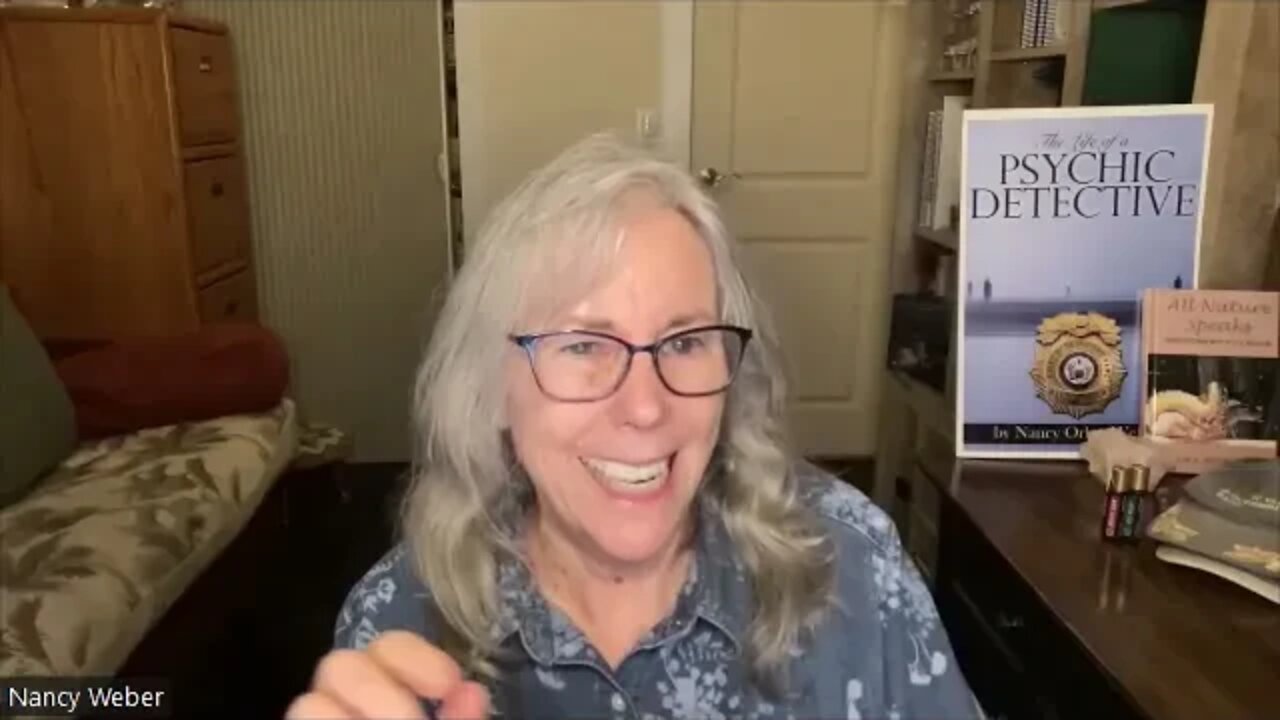

The Life of A Psychic Detective Nancy Orlen Weber

Nancy Orlen Weber is the author of two books, The Life Of A Psychic Detective and All Nature Speaks, Conversations with Pets & Wildlife. She helps people discover their own innate connection with all of life through her writings, workshops, and private sessions.

Nancy resides with her husband in New Jersey and has five children and twelve grandchildren. She enjoys creating pen and ink drawings plus crocheting and donating winter scarves and hats, believing that the fabric of life is woven with love for all.

I've been asked often, "how did you get to do your work?" This is my answer.

The year was 1954, and I was ten years old, living in Brooklyn. On a beautiful spring day in May, my sixth-grade teacher asked me to stay after class and help him with a project. He lied. His hand went up my skirt as he grabbed me, and the other felt like a vise on my chest. The janitor thought it was odd that the door to the classroom was locked. As soon as he unlocked the door, the teacher dropped his hands, and I fled, running the half mile to my home, becoming temporarily mute. Weeks later, I told my best friend, who told her older sister, who told my parents. They did nothing, never talking about it. That experience planted a seed of the need to understand other people's behavior.

It was 1968 when my first husband, Gil, and I moved to Old San Juan, Puerto Rico. We would be there for two years while he did research at a nearby laboratory. While living at 410 Calle Nazagarray, which looked out at the bay and Fortaleza, the number one tourist picture of Puerto Rico, inside our home was a lot darker. Gil was angry at the change in the studies on the brain he thought he would be doing. Eight months into his frustration at work, his rage surfaced all at once. He stormed into the bedroom where I was folding laundry and threw his hands around my neck. I was five months pregnant. Without a word, he attempted to strangle me. I could feel myself passing out. I let myself go limp. He let go assuming he had killed me. Minutes later, I walked into the kitchen, where he was calmly drinking water, and turned the tables. No longer a shy yes to everything, woman. His shock that I was still alive was apparent.

I told him, “I suggest you don’t go to sleep. There may be a knife in your heart.” He stood, mouth open, eyes frozen on me.

With no one to help me, no family, no car, and no phone, I closed myself off to the outside world, attempting to keep my unborn child feeling safe. I gave birth months later, vowing to leave him as soon as possible.

In 1970, we moved back to the Bronx, New York, and I readied myself by looking for both work and someone I could trust to care for my daughter. One day I gave him the same notice he gave me in his attempt to destroy my life. “Leave. I do not love you nor forgive you.” He had just punched a hole in a wall. The force of my conviction was evident as he packed and left. We divorced, and I had sole custody of my daughter. Now disabled due to the violence, I knew I needed to look for nursing work that would fulfill my need to create a greater understanding of the effects of trauma.

That is also when I threw myself into Primal Therapy, Gestalt Therapy, Rolfing, and more. At each session, I felt more of myself and less of the frightened, shy little girl who was afraid of everyone.

A new experimental unit, the Acute Psychiatric Unit of Lincoln hospital in the south Bronx, was opening. At the time, that area had the highest crime rate in the country. The unit had blue walls and a large living room with many tables and chairs. To the left of the living room were twelve single-bed units, and to the right were two offices and a room for resident physicians in training in psychiatry. The teacher for the physicians in training offered me the top research post in psychiatry in New York State when he and the corporation, Health and Hospitals, knew I could get break through the patient's psychosis, sometimes in a few minutes or hours. One new client was admitted with the diagnosis of Catatonic. This had been ongoing for over 20 years. He had remained nonverbal all this time. Sitting opposite him in the central room, open to all who worked there with our chairs six feet apart, I saw his hands constantly moving. I felt it was his way of communicating. I responded as if my hands knew what to say, suspending all thought and imagining my hands would know how to build a friendship.

-

5:31

5:31

Adam Does Movies

22 hours ago $0.12 earnedThe Monkey Movie Review - This Is From The Longlegs Director?

11.3K1 -

14:47

14:47

Tactical Considerations

14 hours ago $0.23 earnedClassic Precision Woox Furiosa Bergara Premier 6.5 CREED

9.88K1 -

40:44

40:44

Rethinking the Dollar

22 hours agoDonald & Elon Head to Fort Knox—What Are They Planning?

7.67K16 -

1:10:15

1:10:15

MTNTOUGH Fitness Lab

1 day ago"My Baseball Career Wasn't Enough": Adam LaRoche's Life-Changing Anti-Trafficking M

6.48K2 -

1:00:12

1:00:12

The Tom Renz Show

18 hours agoComing to America & Coming to Christ

27.4K7 -

1:12:21

1:12:21

TheRyanMcMillanShow

1 day ago $0.04 earnedDebbie Lee: Mother of First Navy Seal Killed In Iraq, Marc Lee - RMS 019

10K1 -

38:05

38:05

Uncommon Sense In Current Times

16 hours ago $0.05 earnedIs Israel Being Forced Into a Bad Deal? David Rubin Exposes the Truth | Uncommon Sense

9.49K9 -

FreshandFit

11 hours agoAfter Hours w/ Girls

118K93 -

2:33:58

2:33:58

TimcastIRL

13 hours agoDan Bongino ACCEPTS Deputy FBI Director, SECRET NSA CHATS EXPOSED w/Joey Mannarino | Timcast IRL

185K102 -

1:09:33

1:09:33

Glenn Greenwald

17 hours agoMichael Tracey Reports from CPAC: Exclusive Interviews with Liz Truss, Steve Bannon & More | SYSTEM UPDATE #412

135K95