Premium Only Content

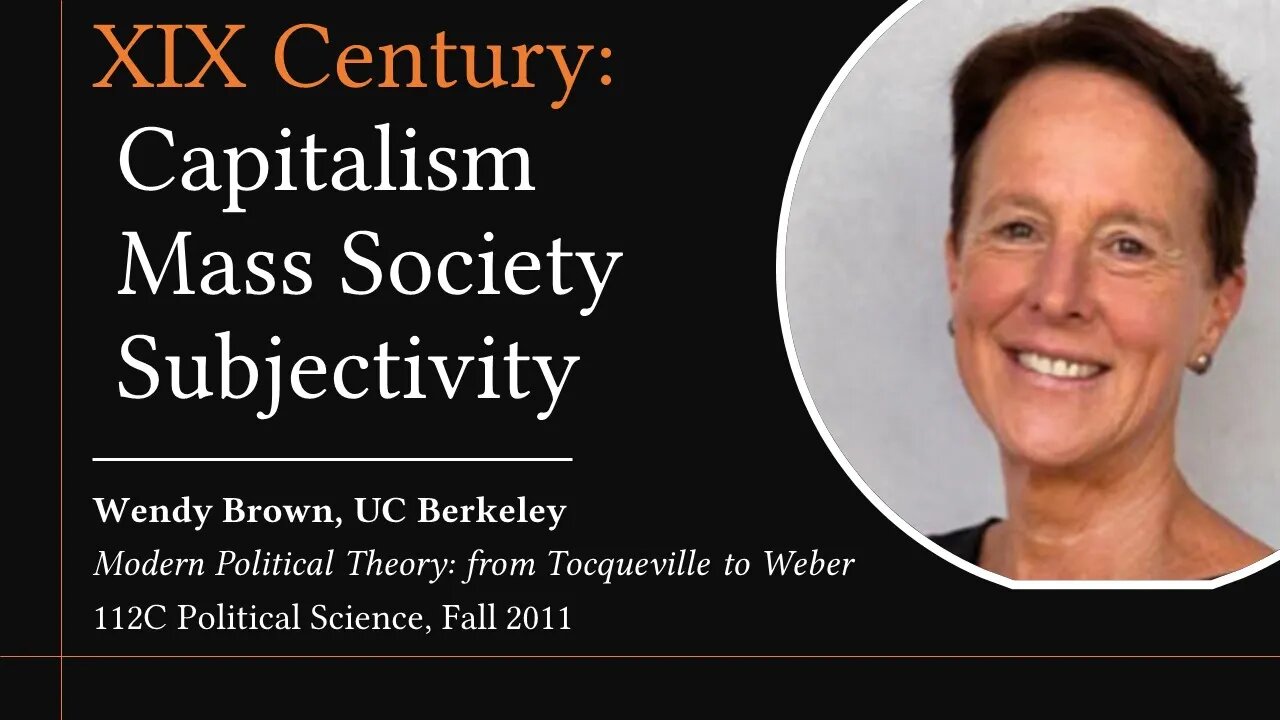

XIX Century: Capitalism, Mass Society, Subjectivity (Wendy Brown, UC Berkeley)

Wendy Brown, UC Berkeley

Modern Political Theory: from Tocqueville to Weber

112C Political Science, Fall 2011

#revolution #capitalism #politicalphilosophy

=== Age of emerging capitalism, mass society and the individual

The 19th century saw a crucially important historical transformation. The West (broadly defined as the Euroatlantic world, namely Europe and the US) has emerged as a dominant civilizational power in the world at the same time beginning to understands itself as the birthplace of democracy.

In this period a particular set of overarching questions has come to the fore, question concerning power, justice, relationship between economics and politics and the nature of democracy. In the words of Alexis de Tocqueville “A new political science is needed for a world itself quite new”, and to answer these questions there appeared a number of theorists of whom two will be covered below: John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx. Before we deal closely with them let us first look at a general sketch of the most important changes that took place in the 19th century Europe. To speak in the broadest possible terms these include the democratic revolutions, the industrial revolution, explosion of capital as a political social and economic force, and finally the rise of mass society, and its counterpart the alienated individual.

This is also the time of the birth of classical Liberalism. This broad political outlook is characterised by a number of features, including the following: the individual is taken as a primary political unit, individual’s liberty is taken as fundamental, and the variously defined equality among individuals comes to be broadly assumed. The political theorists of the 19th century, and to some extent the general culture of the time, come to take these things as given – and liberalism itself increasingly becomes common sense. The questions that preoccupied the 18th century – the attacks on feudal arrangements of power and legitimacy (especially monarchical power), privileges of aristocracy, exclusions based on rank, separation of church from state – all these questions appear to be more or less settled, and legitimacy of government established through representation as well as certain rights of man are also coming to be more and more widely accepted.

That is not to say that all of these changes have come to completion – it is a debated question whether even today we enjoy their fruits – but a clear trend is established. The scope and the definitions of the new democratic vocabulary is also in flux. Who do the rights of man belong to? Are women included? It should not be forgotten that in the United Kingdom women have acquired officially acquired the right to vote only in 1928. Are African-Americans included in the US? Jews in Europe? Colonised peoples within the European Empires? To some extent in one form or another all of these remain open issues to this day.

Nevertheless, crucially the matters that so intensely occupied the 17-18th centuries in political philosophy are no longer at the forefront of the political theory in the 19th century. Instead we see something really new, political theory concerned for the first time with in a big way with society and economy, with questions of how populations are to be managed, governed and ordered. Political and social theory begin to merge: social contours of social life become as important as political institutions. Nature of society and economy become political issues. This is especially true for Marx who will argue that political life is pretty much a derivative of much more fundamental orders of power found at the level of the economic and the social.

The big questions of political theory start to shift away from whether those assumptions are legitimate or not and instead turn to questions and issues that operate inside democratic assumptions. Questions like: is democracy more fundamentally about equality or a about liberty? Thinkers like Tocqueville will say that democracy is crucially defined by egalitarianism, absence of rank and orders established by birth. Others like Mill and Bentham will stress liberty. Marx will argue that you can only get real freedom through true equality, and that existing bourgeois/constitutional democracies haven’t yet achieved either true equality or true freedom.

The value of democracy comes to be more and more of a given, even though there will be argument about what this value consists in. Thus the question becomes: what institutions and what social arrangement best realise the principles and the promises of democracy? Not just whether democracy is right or wrong, but what makes it come true, what realises it? Centralised government or local participation and decentralisation; capitalism or socialism, mass education or the cultivation of an intellectual and cultural elite who will keep democracy to its promise, superior leadership or popular sovereignty and popular power?

TRANSCRIPT IN THE COMMENTS

-

13:10

13:10

Philosophy with Alexander Koryagin

1 year agoAgainst Naïve Universalism: Towards a New Morality

75 -

30:53

30:53

Uncommon Sense In Current Times

1 day ago $2.93 earned"Pardon or Peril? How Biden’s Clemency Actions Could Backfire"

26.9K2 -

40:01

40:01

CarlCrusher

18 hours agoSkinwalker Encounters in the Haunted Canyons of Magic Mesa - ep 4

31.1K2 -

59:44

59:44

PMG

1 day ago $3.32 earned"BETRAYAL - Johnson's New Spending Bill EXPANDS COVID Plandemic Powers"

43.9K14 -

6:48:50

6:48:50

Akademiks

16 hours agoKendrick Lamar and SZA disses Drake and BIG AK? HOLD UP! Diddy, Durk, JayZ update. Travis Hunter RUN

166K28 -

11:45:14

11:45:14

Right Side Broadcasting Network

9 days agoLIVE REPLAY: TPUSA's America Fest Conference: Day Three - 12/21/24

350K28 -

12:19

12:19

Tundra Tactical

16 hours ago $12.92 earnedDaniel Penny Beats Charges in NYC Subway Killing

69K13 -

29:53

29:53

MYLUNCHBREAK CHANNEL PAGE

1 day agoUnder The Necropolis - Pt 1

158K52 -

2:00:10

2:00:10

Bare Knuckle Fighting Championship

3 days agoCountdown to BKFC on DAZN HOLLYWOOD & FREE LIVE FIGHTS!

59.7K3 -

2:53:01

2:53:01

Jewels Jones Live ®

1 day agoA MAGA-NIFICENT YEAR | A Political Rendezvous - Ep. 103

153K39