Premium Only Content

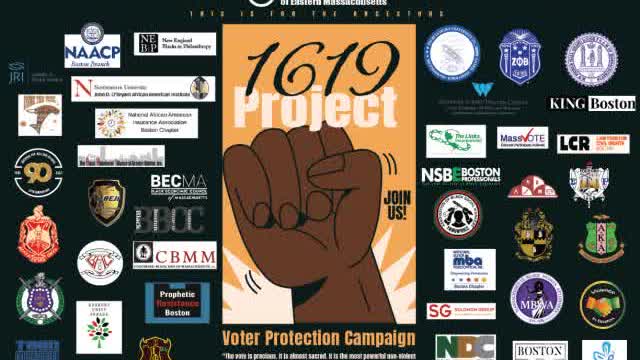

The 1619 Project, A Dalek Precis

========================

This is a precis of the 1619 Project,

created by Nikole Hannah-Jones

This is not an endorsement,

merely an attempt at an abbreviation

=========================

My dad always flew an American flag in our front yard.

My dad was born into a family of sharecroppers on a white plantation in Greenwood, Mississippi, where Black people bent over cotton from can’t-see-in-the-morning to can’t-see-at-night, just as their enslaved ancestors had done not long before.

The Mississippi of my dad’s youth was an apartheid state that subjugated its Black residents—almost half of the population, through breathtaking acts of violence. White residents in Mississippi lynched more Black people than those in any other state in the country.

The army did not end up being his way out. He was passed over for opportunities, his ambition stunted.

Like all the Black men and women in my family, he believed in hard work, but like all the Black men and women in my family, no matter how hard he worked, he never got ahead.

He knew that our people’s contributions to building the richest and most powerful nation in the world were indelible, that the United States simply would not exist without us.

In August 1619, the Jamestown colonists bought twenty to thirty enslaved Africans from English pirates.

Those individuals and their descendants transformed the North American colonies into some of the most successful in the British Empire. Through backbreaking labor, they cleared territory across the Southeast. They taught the colonists to grow rice and to inoculate themselves against smallpox.

After the American Revolution, they grew and picked the cotton that, at the height of slavery, became the nation’s most valuable export, accounting for half of American goods sold abroad and more than two-thirds of the world’s supply.

More than any other group in this country’s history, we have served, generation after generation, in an overlooked but vital role: it is we who have been the perfecters of this democracy.

In June 1776, Thomas Jefferson sat at his portable writing desk in a rented room in Philadelphia and penned those famous words:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

As Jefferson composed his inspiring words, however, a teenage boy who would enjoy none of those rights and liberties waited nearby to serve at his master’s beck and call.

His name was Robert Hemings, and he was the half-Black brother of Jefferson’s wife, Martha, born to her father and a woman he enslaved.

It was common and profitable for white enslavers to keep their half-Black children in slavery. Jefferson, who would later hold in slavery his own children by Hemings’s sister Sally, had chosen Robert Hemings, from among about 130 enslaved people who worked on the forced-labor camp he called Monticello, to accompany him to Philadelphia and ensure his every comfort as he drafted the text making the case for a new republican union based on the individual rights of men.

Jefferson’s fellow white colonists knew that Black people were human beings, but over time the enslavers created a network of laws and customs, astounding in both their precision and their cruelty, designed to strip the enslaved of every aspect of their humanity.

No one voluntarily submits to slavery. Enslaved people had always resisted.

Over the course of the war, thousands of enslaved people would join the British—far outnumbering those who joined the Patriot cause.

One act in particular would alter the course of the Revolution.

The fighting had not yet reached the Southern colonies when, in April 1775, seeking to suppress the rebellion, Virginia’s royal governor, John Murray, the Earl of Dunmore, warned the colonists that if they took up arms there, he would “declare Freedom to the Slaves, and reduce the City of Williamsburg to Ashes.”

Dunmore’s proclamation infuriated white Virginians, making revolutionaries out of them. “All over Virginia, observers noted, the governor’s freedom offer turned neutrals and even loyalists into patriots,” writes the historian Woody Holton in Forced Founders.

In 1772, the court decided the case of James Somerset, an enslaved man from Virginia, who claimed freedom when his owner brought him to Britain.

The British judge decided in Somerset’s favor, proclaiming that British common law did not allow slavery on the soil of the mother country—even as Britain was investing in it and profiting from it in her Caribbean and North American colonies.

Both further enflamed colonists already worried about the British encroaching on their “property” rights.

For men like Washington, Jefferson, and Madison, the Dunmore Proclamation ignited the turn to independence.”

Virginia’s slaveholding elite had grown paranoid.

The specter of their most valuable property absconding to take up arms against them “did more than any other British measure to spur uncommitted white Americans into the camp of rebellion,” wrote the historian Gerald Horne in The Counter-Revolution of 1776.

And yet none of this is part of our founding mythology, which conveniently omits the fact that one of the primary reasons some of the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.

They feared that liberation would enable an abused people to seek vengeance on their oppressors. In many parts of the South, Black people far outnumbered white people.

As Samuel Johnson, an English writer opposed to American independence, quipped, “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?”

The founders recognized this hypocrisy.

Or as the historian Michael Groth put it, “In one sense, slaveholding Patriots went to war in 1775 and declared independence in 1776 to defend their rights to own slaves.”

White sons of Virginia initiated the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

It was Virginia that first enshrined racialized chattel slavery into law, excluding Black people from all civic life and setting a precedent followed throughout the colonies.

Virginia and the rest of the American South constituted one of just five “great slave societies” in the history of the world, according to the historian David W. Blight. This meant that the colony did not simply engage in slavery as many nations had for centuries before; it created a culture where, as Blight puts it, “slavery affected everything about society,” its social relationships, laws, customs, and politics.

By the period of the Revolution, white Virginian elites had traded their reliance on white laborers for the more economically profitable and less politically troublesome enslaved African labor.

In 1776, Virginia held 40 percent of all enslaved people in the mainland colonies.

The slave codes helped to ensure that poorer white Virginians felt relatively empowered. “

Whiteness proved a powerful unifying elixir for the burgeoning nation.

Whether laborer or elite planter, “neither was a slave. And both were equal in not being slaves.

In fact, some might argue that this nation was founded not as a democracy but as a slavocracy.

During the Constitution’s ratification in the 1780s, a few bold Americans of both races sustained a new abolitionist movement. They considered the Constitution deceitful.

“The words [are] dark and ambiguous; such as no plain man of common sense would have used,” wrote the abolitionist Samuel Bryan.

They “are evidently chosen to conceal from Europe, that in this enlightened country, the practice of slavery has its advocates among men in the highest stations.”

As Frederick Douglass would explain in 1849, the Constitution bound the nation “to do the bidding of the slave holder, to bring out the whole naval and military power of the country, to crush the refractory slaves into obedience to their cruel masters.”

He characterized the Constitution as so “cunningly” framed that “no one would have imagined that it recognized or sanctioned slavery.

But having a terrestrial, and not a celestial origin, we find no difficulty in ascertaining its meaning in all the parts which we allege relate to slavery. Slavery existed before the Constitution…. Slaveholders took a large share in making it.”

Many white Virginians fretted that continuing to import Africans would produce a frighteningly dangerous ratio for a white population well aware of the possibility of deadly insurrections.

Further, years of tobacco growing had depleted the soil, and landowners like Jefferson were turning to crops that required less labor, such as wheat.

That meant they needed fewer enslaved people to turn a profit.

White Virginians, therefore, stood to make money by cutting off the supply of new people from Africa and instead filling the demand in the Deep South for enslaved labor by selling their surplus laborers to the cotton and sugar forced-labor camps in Georgia and South Carolina.

Jefferson himself considered the people he enslaved in the coldest economic terms, saying he calculated that a “woman who brings a child every two years as more profitable than the best man of the farm.

What she produces is an addition to capital, while his labors disappear in mere consumption.”

With independence, the founding fathers could no longer blame slavery on Britain.

The sin became this nation’s own, and so, too, the need to cleanse it.

By the early 1800s, according to the legal historians Robert J Cottrol, Raymond T Diamond, and Leland B Ware, white Americans, whether they engaged in slavery or not, “had a considerable psychological as well as economic investment in the doctrine of Black inferiority.”

Racist justifications for slavery gained ground during the mid-nineteenth century. The majority of the Supreme Court enshrined this thinking in the law in its 1857 Dred Scott decision, declaring that Black people, whether enslaved or free, came from a “slave” race.

This made them permanently inferior to white people and, therefore, incompatible with American democracy.

Democracy existed for citizens, and the “Negro race,” the court ruled, was “a separate class of persons,” one the founders had “not regarded as a portion of the people or citizens of the Government” and who had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

Prior to becoming president, as a lawyer and politician in Illinois, Lincoln himself had believed that free Black people amounted to a “troublesome presence” incompatible with a democracy intended only for white people. “Free them, and make them politically and socially our equals?” he had asked just a few years before the Civil War. “My own feelings will not admit of this; and if mine would, we well know that those of the great mass of white people will not.”

And so, Lincoln decided that the same document that would emancipate millions of enslaved people in rebel territory would also call for them, once free, to voluntarily leave their country and resettle elsewhere.

Many white Americans across the political spectrum believed Black people held no place in American society as free citizens, and some abolitionists—Black and white—did not think free Black people would ever know real freedom here.

“Why should they leave this country? This is, perhaps, the first question for proper consideration,” Lincoln told his visitors. “You and we are different races…. Your race suffers very greatly, many of them, by living among us, while ours suffer from your presence. In a word, we suffer on each side.”

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the final version of the Emancipation Proclamation.

It no longer included the mention of colonization, and it also provided for something Black leaders had long advocated for: the ability for Black men to enlist in the Union and fight for their freedom.

Eventually, some two hundred thousand Black Americans would serve in the Union, accounting for one in ten Union soldiers.

In our national story, we crown Lincoln the Great Emancipator, the president who ended slavery, demolished the racist South, and ushered in the free nation our founders set forth.

But this narrative, like so many others, requires more nuance.

Douglass would never forget that the president initially suggested that the only solution, after abolishing an enslavement that had lasted for centuries, was for Black Americans to leave the country they helped to build.

More than a decade later, organizers asked Douglass to eulogize the assassinated president at the unveiling of a new memorial for Lincoln and the freedmen in Washington, D.C. The abolitionist, whose mother had been sold away from him when he was a young child, had met with Lincoln a few times during his presidency and had repeatedly prodded Lincoln in his writings and speeches to emancipate the enslaved.

That the formerly enslaved did not take up Lincoln’s offer to abandon these lands is an astounding testament to their belief in this nation’s founding ideals.

During this nation’s brief period of Reconstruction, from 1865 to 1877, formerly enslaved people zealously engaged with the democratic process.

A year after Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment, outlawing slavery, Black Americans, exerting their new political power, lobbied white legislators to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the nation’s first such law and one of the greatest pieces of civil rights legislation in American history.

In 1868, Congress ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, ensuring citizenship to Black Americans and all people born in the United States.

Today, thanks to this amendment, every child born here, and all their progeny thereafter, gains automatic citizenship.

The Fourteenth Amendment also, for the first time, constitutionally guaranteed equal protection and codified equality in the law.

Finally, in 1870, Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment, establishing the most critical aspect of democracy and citizenship—the right to vote—to all men regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Demonstrating just how brief this period would be, Revels and Blanche Bruce, who was elected four years later, would go from being the first Black men elected to the last for nearly a hundred years, until Edward Brooke of Massachusetts took office in 1967.

Remarkably, in 1873 the University of South Carolina became the only state-sponsored college in the South to fully integrate, becoming majority Black—just like the state itself—by 1876.

When white former Confederates regained power a year later, they closed the university. After three years, they reopened it as an all-white institution; it would remain that way for nearly a century, until a court-ordered desegregation in 1963.

But it would not last.

In 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes, in order to secure a compromise with Southern Democrats that would grant him the presidency in a contested election, agreed to pull the remaining federal troops from the South.

Democracy would not return to the South for nearly a century.

As the racially egalitarian spirit of post–Civil War America evaporated under the desire for national reunification, Black Americans, simply by existing, served as a problematic reminder of this nation’s failings.

White America dealt with this inconvenience by constructing a savagely enforced system of racial apartheid that excluded Black people almost entirely from mainstream American life—a system so grotesque that Nazi Germany would later take inspiration from it for its own racist policies.

Despite the guarantees of equality in the Fourteenth Amendment, the Supreme Court’s landmark Plessy versus Ferguson decision in 1896 declared the racial segregation of Black Americans constitutional.

States like California joined Southern states in barring Black people from marrying white people, while local school boards in Illinois and New Jersey mandated segregated schools for Black and white children.

White Americans maintained this caste system through wanton racial terrorism.

Many white Americans saw Black men in the uniforms of America’s armed services not as patriotic but as exhibiting a dangerous pride.

Hundreds of Black veterans were beaten, maimed, shot, and lynched. The extremity of the violence was a symptom of the psychological mechanism necessary to absolve white Americans of their country’s original sin.

To answer the question of how they could prize liberty abroad while simultaneously denying liberty to an entire race back home, white Americans resorted to the same racist ideology that Jefferson and the framers had used at the nation’s founding: that Black people were an inferior race whose degraded status justified their treatment.

This ideology did not simply disappear once slavery ended.

In response to Black demands for these rights, white Americans strung them from trees, beat them and dumped their bodies in muddy rivers, assassinated them in their front yards, firebombed them on buses, mauled them with dogs, peeled back their skin with fire hoses, and murdered their children with explosives set off inside a church.

Because of Black Americans, Black and brown immigrants from across the globe are able to come to the United States and live in a country in which legal discrimination is no longer allowed. It is truly an American irony that some Asian Americans, among the groups able to immigrate to the United States in large numbers because of the Black civil rights struggle, have sued universities to end programs designed to help the descendants of the enslaved.

The truth is that as much democracy as this nation has today, it has been borne on the backs of Black resistance and visions for equality.

They say our people were born on the water.

But as the sociologist Glenn Bracey writes, “Out of the ashes of white denigration, we gave birth to ourselves.”

When the world listens to quintessentially American music, it is our voice they hear. The sorrow songs we sang in the fields to soothe our physical pain and find hope in a freedom we did not expect to know until we died became American gospel.

Our speech and fashion and the drum of our music echo Africa but are more than African.

For centuries, white Americans have been trying to solve the “Negro problem.”

Black people suffered under slavery for 250 years; we have been legally “free” for just fifty. Yet in that briefest of spans, despite continuing to face rampant discrimination, and despite there never having been a genuine effort to redress the wrongs of slavery and the century of racial apartheid that followed, Black Americans have made astounding progress, not only for ourselves but also for all Americans.

We were told once, by virtue of our bondage, that we could never be American. But it was by virtue of our bondage that we became the most American of all.

-

14:44

14:44

PukeOnABook

30 days agoRahan. Episode 131. By Roger Lecureux. The Barrage of Demons. A Puke (TM) Comic.

891 -

LIVE

LIVE

Flyover Conservatives

20 hours agoGarrett Ziegler Breaks Down Special Councilor’s Report on Hunter Biden. Insights for Trump’s Top Picks. | FOC Show

351 watching -

44:54

44:54

Steve-O's Wild Ride! Podcast

9 hours ago $6.20 earnedMark Wahlberg Threatened To Beat Up Jackass Cast Member - Wild Ride #251

71.1K9 -

DVR

DVR

Josh Pate's College Football Show

3 hours ago $0.36 earnedCFB Dynasties & Villains | Marcus Freeman OR Ryan Day | 2025 Sleeper Teams | Cole Cubelic Joins

2.44K -

1:00:26

1:00:26

The StoneZONE with Roger Stone

2 hours agoSHOCKING NEW TAPE PROVES LBJ KILLED JFK! | The StoneZONE w/ Roger Stone

27.6K9 -

1:44:33

1:44:33

ObaTheGreat

4 hours agoCrypto vs The World w/ Oba The Great And YaBoySkey

24.6K -

LIVE

LIVE

VOPUSARADIO

2 days agoPOLITI-SHOCK! "COUNTDOWN TO TRUMP" & THE GLOBALISTS BURNING IT ALL DOWN..LITERALLY!

103 watching -

44:34

44:34

Kimberly Guilfoyle

7 hours agoCountdown to Inauguration Day, Plus California in Crisis, Live with Joel Pollack & Roger Stone | Ep. 189

105K55 -

1:32:41

1:32:41

Redacted News

6 hours agoBiden's 'SNEAKY' plot to slow down Trump REVEALED | Redacted w Clayton Morris

114K171 -

56:32

56:32

Candace Show Podcast

6 hours agoOH SNAP! Justin Baldoni Is Now Suing Blake Lively and Ryan Reynolds PERSONALLY | Candace Ep 134

107K171