-

When the Justice System Fails: No Presumption of Innocence (1974)

The Memory HoleThis film delves into the harrowing reality of the British prison system, shining a spotlight on the plight of individuals incarcerated without trial or convicted of minor offenses. It uncovers a disturbing truth: a staggering number of individuals, including first-time offenders, minors, and innocent people, find themselves trapped within a system that bears a resemblance to oppressive regimes devoid of fundamental human rights. The documentary paints a grim picture of the conditions within these prisons, where individuals endure deplorable treatment and confinement. Through firsthand accounts, viewers witness the stark and often inhumane conditions faced by inmates—overcrowded cells, unsanitary facilities, restricted movement, and limited access to essential medications. Stories of individuals forced to share cells with hardened criminals underscore the severe repercussions of the system's failings. This investigation reveals a startling statistic: a significant portion of those remanded in custody are eventually proven innocent or receive minimal penalties. This revelation prompts a critical examination of the judicial process, with insights from legal professionals highlighting the shortcomings of magistrates who may overlook crucial case details or adopt punitive attitudes without due consideration. Moreover, the documentary sheds light on the devastating mental toll exacted on prisoners, evident in the alarming rate of attempted suicides within these institutions. The despair and hopelessness experienced by those on remand serve as a poignant reminder of their dire circumstances and the absence of proper guidance and support within a justice system that feels distant and indifferent to their plight. The documentary is a powerful exposé that challenges the very essence of justice and raises poignant questions about the treatment of individuals ensnared in a system that often fails to uphold their rights and dignity. A presumption of guilt is any presumption within the criminal justice system that a person is guilty of a crime, for example a presumption that a suspect is guilty unless or until proven to be innocent.[1] Such a presumption may legitimately arise from a rule of law or a procedural rule of the court or other adjudicating body which determines how the facts in the case are to be proved, and may be either rebuttable or irrebuttable. An irrebuttable presumption of fact may not be challenged by the defense, and the presumed fact is taken as having been proved. A rebuttable presumption shifts the burden of proof onto the defense, who must collect and present evidence to prove the suspect's innocence, in order to obtain acquittal.[2] Rebuttable presumptions of fact, arising during the course of a trial as a result of specific factual situations (for example that the accused has taken flight),[3] are common; an opening presumption of guilt based on the mere fact that the suspect has been charged is considered illegitimate in many countries,[4] and contrary to international human rights standards. In the United States, an irrebuttable presumption of guilt is considered to be unconstitutional. Informal and legally illegitimate presumptions of guilt may also arise from the attitudes or prejudices of those such as judges, lawyers or police officers who administer the system. Such presumptions may result in suspects who are innocent being brought before a court to face criminal charges, with a risk of improperly being found guilty. Definition According to Herbert L. Packer, "It would be a mistake to think of the presumption of guilt as the opposite of the presumption of innocence that we are so used to thinking of as the polestar of the criminal process and which... occupies an important position in the Due Process Model."[5] The presumption of guilt prioritizes speed and efficiency over reliability, and prevails when due process is absent.[5] In State v. Brady (1902) 91 NW 801, Weaver J said "'Presumptions of guilt' and 'prima facie' cases of guilt in the trial of a party charged with crime mean no more than that from the proof of certain facts the jury will be warranted in convicting the accused of the offense with which he is charged".[6] Human rights In Director of Public Prosecutions v. Labavarde and Anor, Neerunjun C.J. said that article 11(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and article 6(2) of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms would be infringed if "the whole burden is ... cast on the defence by the creation of a presumption of guilt on the mere preferment of the criminal charge".[7][8] Inquisitorial systems It is sometimes said that in inquisitorial systems, a defendant is guilty until proven innocent.[9] It has also been said that this is a myth,[10] as well as a former "common conceit of English lawyers" who asserted this was the case in France.[11][12] A presumption of guilt is incompatible with the presumption of innocence and moves an accusational system of justice toward the inquisitional.[13] Common law presumptions There have existed at least two types of presumption of guilt under the law of England, which arose from a rule of law or a procedural rule of the court or other adjudicating body and determined how the facts in the case were to be proven, and could be either rebuttable or irrebuttable. Those were:[14] Presumption of guilt arising from the conduct of the party charged Presumption of guilt arising from the possession of provable stolen property Consequences Plea bargaining has been said to involve a presumption of guilt.[15] The American Bar Association states that people with limited resources accused of a crime "find themselves trapped by a system that presumes their guilt."[16] Presumption of guilt on the part of investigators may result in false confessions,[17] as was postulated in Making a Murderer, an American documentary television series.[18] Preventive detention, detaining an individual for a crime they may commit, has been said to involve a presumption of guilt, or something very close to one.[19][20] A fixed penalty notice or on-the-spot fine are penalties issued by police for minor offences which are difficult and expensive to appeal.[21] Unconstitutional, illegitimate and informal presumptions An irrebuttable presumption of guilt is unconstitutional in the United States.[22] An arrest, however, often becomes synonymous or "fused" with guilt, postulates Anna Roberts, a United States law professor.[23] In the minds of jurors, the person charged must have done something wrong.[18] In Japan the criminal justice system has been criticized for its wide use of detentions during which suspects are forced to make false confessions during interrogations.[24][25] In 2020, Japan's Justice Minister Masako Mori tweeted regarding the need for someone to prove their innocence in a court of law. She later deleted the tweet and called it "verbal gaffe".[26] High Court judge Sir Richard Henriques has criticized UK police training and methods which allegedly assert that "only 0.1% of rape allegations are false", and in which all complainants are treated as "victims" from the start.[27][28] It is difficult to assess the true prevalence of false rape allegations, but it is generally agreed that rape accusations are false at least 2% to 10% of the time, with a greater proportion of cases not being proven to be true or false.[29][30] The American actor and producer Jeremy Piven has spoken out against the Me Too movement, which he claims, "put lives in jeopardy without a hearing, due process or evidence". Writing about Piven's comment, journalist Brendan O'Neill, suggests that the presumption of innocence is being weakened.[31] An illegitimate presumption of guilt may be caused or motivated by factors such as racial prejudice,[32] "media frenzy",[18][33] cognitive bias,[18][32][34] and others. See also Blackstone's ratio False accusation Give me the man and I will give you the case against him Kangaroo court Prosecutor's fallacy Understanding References Raj Bhala. Modern GATT Law: A Treatise on the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. Sweet & Maxwell. 2005. Page 935. Roscoe, H.; Granger, T.C.; Sharswood, G. (1852). A Digest of the Law of Evidence in Criminal Cases. T. & J.W. Johnson. Retrieved 11 March 2020. This is how presumptions have traditionally been classified: Zuckerman, The Principles of Criminal Evidence, 1989, pp 112 to 115. An irrebuttable presumption of guilt is unconstitutional in the United States: Florida Businessmen for Free Enterprise v. State of Fla. See United States Code Annotated. An example of a rebuttable presumption of guilt is (1983) 301 SE 2d 984. "The presumption of guilt arising from the flight of the accused is a presumption of fact": Hickory v United States (1896) 160 United States Reports 408 (headnote published 1899). Ralph A Newman (ed). Equity in the World's Legal Systems. Établissements Émile Bruylant. 1973. p 559. Packer, Herbert L. (November 1964). "Two Models of the Criminal Process". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania. 113 (1): 1–68. doi:10.2307/3310562. JSTOR 3310562. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019. Wigmore, John Henry (1905). A Treatise on the System of Evidence in Trials at Common Law. Vol. 4. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 3562, Note 1 to section 2513 – via Internet Archive. Director of Public Prosecutions v. Labavarde and Anor. (1965) 44 International Law Reports 104 at 106; Mauritius Reports, 1965 72 at 74, Mauritius, High Court Lauterpacht, E. (1972). International Law Reports. International Law Reports 160 Volume Hardback Set. Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-521-46389-8. Retrieved 11 March 2020. For example, Scottish International, vols 6 to 7, p 146 Dammer and Albanese. Comparative Criminal Justice Systems. Wadsworth. 2014. p 128. Roberts and Redmayne. Innovations in Evidence and Proof: Integrating Theory, Research and Teaching. Hart Publishing. Oxford and Portland, Oregon. 2007. p 379. For the origins of this belief in South Africa, see (1970) 87 South African Law Journal 413 Ingraham, Barton L. (1996). "The Right of Silence, the Presumption of Innocence, the Burden of Proof, and a Modest Proposal". Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology. 86 (2): 559. doi:10.2307/1144036. JSTOR 1144036. Retrieved 31 August 2021. Roscoe, H.; Granger, T.C. (1840). A Digest of the Law of Evidence in Criminal Cases. p. 13. Retrieved 11 March 2020. "5. The Presumption of Guilt" (1973) 82 Yale Law Journal 312; "The Skeleton of Plea Bargaing" (1992) 142 New Law Journal 1373; (1995) 14 UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal 129 & 130; (1986) 77 Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 950; Stumpf, American Judicial Politics, Prentice Hall, 1998, pp 305 & 328; Rhodes, Plea Bargaining: Who Gains? Who Loses?, Institute for Law and Social Research, 1978, p 9. Lewis, John; Stevenson, Bryan (1 January 2014). "On the Presumption of Guilt". American Bar. Green and Heilbrun, Wrightsman's Psychology and the Legal System, 8th Ed, Wadsworth, 2014, p 169; Roesch and Zapf and Hart, Forensic Psychology and Law, Wiley, 2010, p 158, Kocsis (ed), Applied Criminal Psychology, Charles C Thomas, 2009, p 200; Michael Marshall, "Police Presumption of Guilt Key in False Confessions". 12 November 2002. University of Virginia School of Law. Findley, Keith (19 January 2016). "Opinion | The presumption of innocence exists in theory, not reality". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2020. "Preventive Detention: Prevention of Human Rights" (1991) 2 Yale Journal of Law and Liberation 29 at 31; Selected Decisions of the Human Rights Committee under the Optional Protocol, United Nations, 2007, vol 8, p 347 New York Review, 'How internment became legal' Archived 8 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine, John Townsend Rich, 22/6/2017 Goodman, Emily Jane (7 October 2010). "With Parking Tickets, New Yorkers Are Guilty Until Proven Innocent". Gotham Gazette. Archived from the original on 21 November 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2020. Florida Businessmen for Free Enterprise v. State of Fla (1980) 499 F.Supp. 346. See United States Code Annotated. Roberts, Anna (23 April 2018). "Arrests As Guilt". SSRN 3167521. Hirano, Keiji (13 October 2005). "Justice system flawed by presumed guilt". Japan Times Online. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2020. Kingston, Jeff (8 January 2020). "The Carlos Ghosn case shines a light into the dark corners of Japanese justice". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020. Adelstein, Jake; Salmon, Andrew (13 January 2020). "'Guilty until proven guilty' in Japan and Korea". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020. ""If he's clean as he says he is, then he should fairly and squarely prove his innocence in the court of law."" Marco Giannangeli, "Police must stop training 'Presumption of Guilt', says High Court judge" Archived 7 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Daily Express, 24 December 2017. Accessed 6 February 2018. "Former High Court judge warns calling complainants 'victims' creates presumption of guilt", Scottish Legal News, 6 August 2019 DiCanio, M. The encyclopedia of violence: origins, attitudes, consequences. New York: Facts on File, 1993. ISBN 978-0-8160-2332-5. Lisak, David; Gardinier, Lori; Nicksa, Sarah C.; Cote, Ashley M. (2010). "False Allegations of Sexual Assault: An Analysis of Ten Years of Reported Cases". Violence Against Women. 16 (12): 1318–1334. doi:10.1177/1077801210387747. PMID 21164210. S2CID 15377916. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2018. Brendan O'Neill, "Whatever Happened to the Presumption of Innocence?" Archived 7 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Los Angeles Times, 16 November 2017. Accessed 6 February 2018. Stevenson, Bryan (24 June 2017). "A Presumption of Guilt". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2020. "SHEPPARD v. MAXWELL (1966), No. 490, Argued: February 28, 1966 Decided: June 6, 1966". FindLaw's United States Supreme Court. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019. "Cognitive Bias and Its Impact on Expert Witnesses and the Court". Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019. Further reading "Prima Facie Presumptions of Guilt" (1972) 121 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 531 Fellman. "Statutory Presumptions of Guilt". The Defendant's Rights Today. University of Wisconsin Press. 1977. p 106. Martin, "The Burden of Proof as Affected by Statutory Presumptions of Guilt" (1939) 17 Canadian Bar Review 37 Roscoe, H.; Granger, T.C. (1840). A Digest of the Law of Evidence in Criminal Cases. Wharton. A Treatise on the Criminal Law of the United States. 1857. Sections 714, 727, 728 Presumption of Guilt: The Global Overuse of Pretrial Detention published by Open Society Foundations377 views

The Memory HoleThis film delves into the harrowing reality of the British prison system, shining a spotlight on the plight of individuals incarcerated without trial or convicted of minor offenses. It uncovers a disturbing truth: a staggering number of individuals, including first-time offenders, minors, and innocent people, find themselves trapped within a system that bears a resemblance to oppressive regimes devoid of fundamental human rights. The documentary paints a grim picture of the conditions within these prisons, where individuals endure deplorable treatment and confinement. Through firsthand accounts, viewers witness the stark and often inhumane conditions faced by inmates—overcrowded cells, unsanitary facilities, restricted movement, and limited access to essential medications. Stories of individuals forced to share cells with hardened criminals underscore the severe repercussions of the system's failings. This investigation reveals a startling statistic: a significant portion of those remanded in custody are eventually proven innocent or receive minimal penalties. This revelation prompts a critical examination of the judicial process, with insights from legal professionals highlighting the shortcomings of magistrates who may overlook crucial case details or adopt punitive attitudes without due consideration. Moreover, the documentary sheds light on the devastating mental toll exacted on prisoners, evident in the alarming rate of attempted suicides within these institutions. The despair and hopelessness experienced by those on remand serve as a poignant reminder of their dire circumstances and the absence of proper guidance and support within a justice system that feels distant and indifferent to their plight. The documentary is a powerful exposé that challenges the very essence of justice and raises poignant questions about the treatment of individuals ensnared in a system that often fails to uphold their rights and dignity. A presumption of guilt is any presumption within the criminal justice system that a person is guilty of a crime, for example a presumption that a suspect is guilty unless or until proven to be innocent.[1] Such a presumption may legitimately arise from a rule of law or a procedural rule of the court or other adjudicating body which determines how the facts in the case are to be proved, and may be either rebuttable or irrebuttable. An irrebuttable presumption of fact may not be challenged by the defense, and the presumed fact is taken as having been proved. A rebuttable presumption shifts the burden of proof onto the defense, who must collect and present evidence to prove the suspect's innocence, in order to obtain acquittal.[2] Rebuttable presumptions of fact, arising during the course of a trial as a result of specific factual situations (for example that the accused has taken flight),[3] are common; an opening presumption of guilt based on the mere fact that the suspect has been charged is considered illegitimate in many countries,[4] and contrary to international human rights standards. In the United States, an irrebuttable presumption of guilt is considered to be unconstitutional. Informal and legally illegitimate presumptions of guilt may also arise from the attitudes or prejudices of those such as judges, lawyers or police officers who administer the system. Such presumptions may result in suspects who are innocent being brought before a court to face criminal charges, with a risk of improperly being found guilty. Definition According to Herbert L. Packer, "It would be a mistake to think of the presumption of guilt as the opposite of the presumption of innocence that we are so used to thinking of as the polestar of the criminal process and which... occupies an important position in the Due Process Model."[5] The presumption of guilt prioritizes speed and efficiency over reliability, and prevails when due process is absent.[5] In State v. Brady (1902) 91 NW 801, Weaver J said "'Presumptions of guilt' and 'prima facie' cases of guilt in the trial of a party charged with crime mean no more than that from the proof of certain facts the jury will be warranted in convicting the accused of the offense with which he is charged".[6] Human rights In Director of Public Prosecutions v. Labavarde and Anor, Neerunjun C.J. said that article 11(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and article 6(2) of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms would be infringed if "the whole burden is ... cast on the defence by the creation of a presumption of guilt on the mere preferment of the criminal charge".[7][8] Inquisitorial systems It is sometimes said that in inquisitorial systems, a defendant is guilty until proven innocent.[9] It has also been said that this is a myth,[10] as well as a former "common conceit of English lawyers" who asserted this was the case in France.[11][12] A presumption of guilt is incompatible with the presumption of innocence and moves an accusational system of justice toward the inquisitional.[13] Common law presumptions There have existed at least two types of presumption of guilt under the law of England, which arose from a rule of law or a procedural rule of the court or other adjudicating body and determined how the facts in the case were to be proven, and could be either rebuttable or irrebuttable. Those were:[14] Presumption of guilt arising from the conduct of the party charged Presumption of guilt arising from the possession of provable stolen property Consequences Plea bargaining has been said to involve a presumption of guilt.[15] The American Bar Association states that people with limited resources accused of a crime "find themselves trapped by a system that presumes their guilt."[16] Presumption of guilt on the part of investigators may result in false confessions,[17] as was postulated in Making a Murderer, an American documentary television series.[18] Preventive detention, detaining an individual for a crime they may commit, has been said to involve a presumption of guilt, or something very close to one.[19][20] A fixed penalty notice or on-the-spot fine are penalties issued by police for minor offences which are difficult and expensive to appeal.[21] Unconstitutional, illegitimate and informal presumptions An irrebuttable presumption of guilt is unconstitutional in the United States.[22] An arrest, however, often becomes synonymous or "fused" with guilt, postulates Anna Roberts, a United States law professor.[23] In the minds of jurors, the person charged must have done something wrong.[18] In Japan the criminal justice system has been criticized for its wide use of detentions during which suspects are forced to make false confessions during interrogations.[24][25] In 2020, Japan's Justice Minister Masako Mori tweeted regarding the need for someone to prove their innocence in a court of law. She later deleted the tweet and called it "verbal gaffe".[26] High Court judge Sir Richard Henriques has criticized UK police training and methods which allegedly assert that "only 0.1% of rape allegations are false", and in which all complainants are treated as "victims" from the start.[27][28] It is difficult to assess the true prevalence of false rape allegations, but it is generally agreed that rape accusations are false at least 2% to 10% of the time, with a greater proportion of cases not being proven to be true or false.[29][30] The American actor and producer Jeremy Piven has spoken out against the Me Too movement, which he claims, "put lives in jeopardy without a hearing, due process or evidence". Writing about Piven's comment, journalist Brendan O'Neill, suggests that the presumption of innocence is being weakened.[31] An illegitimate presumption of guilt may be caused or motivated by factors such as racial prejudice,[32] "media frenzy",[18][33] cognitive bias,[18][32][34] and others. See also Blackstone's ratio False accusation Give me the man and I will give you the case against him Kangaroo court Prosecutor's fallacy Understanding References Raj Bhala. Modern GATT Law: A Treatise on the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. Sweet & Maxwell. 2005. Page 935. Roscoe, H.; Granger, T.C.; Sharswood, G. (1852). A Digest of the Law of Evidence in Criminal Cases. T. & J.W. Johnson. Retrieved 11 March 2020. This is how presumptions have traditionally been classified: Zuckerman, The Principles of Criminal Evidence, 1989, pp 112 to 115. An irrebuttable presumption of guilt is unconstitutional in the United States: Florida Businessmen for Free Enterprise v. State of Fla. See United States Code Annotated. An example of a rebuttable presumption of guilt is (1983) 301 SE 2d 984. "The presumption of guilt arising from the flight of the accused is a presumption of fact": Hickory v United States (1896) 160 United States Reports 408 (headnote published 1899). Ralph A Newman (ed). Equity in the World's Legal Systems. Établissements Émile Bruylant. 1973. p 559. Packer, Herbert L. (November 1964). "Two Models of the Criminal Process". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania. 113 (1): 1–68. doi:10.2307/3310562. JSTOR 3310562. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019. Wigmore, John Henry (1905). A Treatise on the System of Evidence in Trials at Common Law. Vol. 4. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 3562, Note 1 to section 2513 – via Internet Archive. Director of Public Prosecutions v. Labavarde and Anor. (1965) 44 International Law Reports 104 at 106; Mauritius Reports, 1965 72 at 74, Mauritius, High Court Lauterpacht, E. (1972). International Law Reports. International Law Reports 160 Volume Hardback Set. Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-521-46389-8. Retrieved 11 March 2020. For example, Scottish International, vols 6 to 7, p 146 Dammer and Albanese. Comparative Criminal Justice Systems. Wadsworth. 2014. p 128. Roberts and Redmayne. Innovations in Evidence and Proof: Integrating Theory, Research and Teaching. Hart Publishing. Oxford and Portland, Oregon. 2007. p 379. For the origins of this belief in South Africa, see (1970) 87 South African Law Journal 413 Ingraham, Barton L. (1996). "The Right of Silence, the Presumption of Innocence, the Burden of Proof, and a Modest Proposal". Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology. 86 (2): 559. doi:10.2307/1144036. JSTOR 1144036. Retrieved 31 August 2021. Roscoe, H.; Granger, T.C. (1840). A Digest of the Law of Evidence in Criminal Cases. p. 13. Retrieved 11 March 2020. "5. The Presumption of Guilt" (1973) 82 Yale Law Journal 312; "The Skeleton of Plea Bargaing" (1992) 142 New Law Journal 1373; (1995) 14 UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal 129 & 130; (1986) 77 Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 950; Stumpf, American Judicial Politics, Prentice Hall, 1998, pp 305 & 328; Rhodes, Plea Bargaining: Who Gains? Who Loses?, Institute for Law and Social Research, 1978, p 9. Lewis, John; Stevenson, Bryan (1 January 2014). "On the Presumption of Guilt". American Bar. Green and Heilbrun, Wrightsman's Psychology and the Legal System, 8th Ed, Wadsworth, 2014, p 169; Roesch and Zapf and Hart, Forensic Psychology and Law, Wiley, 2010, p 158, Kocsis (ed), Applied Criminal Psychology, Charles C Thomas, 2009, p 200; Michael Marshall, "Police Presumption of Guilt Key in False Confessions". 12 November 2002. University of Virginia School of Law. Findley, Keith (19 January 2016). "Opinion | The presumption of innocence exists in theory, not reality". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2020. "Preventive Detention: Prevention of Human Rights" (1991) 2 Yale Journal of Law and Liberation 29 at 31; Selected Decisions of the Human Rights Committee under the Optional Protocol, United Nations, 2007, vol 8, p 347 New York Review, 'How internment became legal' Archived 8 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine, John Townsend Rich, 22/6/2017 Goodman, Emily Jane (7 October 2010). "With Parking Tickets, New Yorkers Are Guilty Until Proven Innocent". Gotham Gazette. Archived from the original on 21 November 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2020. Florida Businessmen for Free Enterprise v. State of Fla (1980) 499 F.Supp. 346. See United States Code Annotated. Roberts, Anna (23 April 2018). "Arrests As Guilt". SSRN 3167521. Hirano, Keiji (13 October 2005). "Justice system flawed by presumed guilt". Japan Times Online. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2020. Kingston, Jeff (8 January 2020). "The Carlos Ghosn case shines a light into the dark corners of Japanese justice". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020. Adelstein, Jake; Salmon, Andrew (13 January 2020). "'Guilty until proven guilty' in Japan and Korea". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020. ""If he's clean as he says he is, then he should fairly and squarely prove his innocence in the court of law."" Marco Giannangeli, "Police must stop training 'Presumption of Guilt', says High Court judge" Archived 7 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Daily Express, 24 December 2017. Accessed 6 February 2018. "Former High Court judge warns calling complainants 'victims' creates presumption of guilt", Scottish Legal News, 6 August 2019 DiCanio, M. The encyclopedia of violence: origins, attitudes, consequences. New York: Facts on File, 1993. ISBN 978-0-8160-2332-5. Lisak, David; Gardinier, Lori; Nicksa, Sarah C.; Cote, Ashley M. (2010). "False Allegations of Sexual Assault: An Analysis of Ten Years of Reported Cases". Violence Against Women. 16 (12): 1318–1334. doi:10.1177/1077801210387747. PMID 21164210. S2CID 15377916. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2018. Brendan O'Neill, "Whatever Happened to the Presumption of Innocence?" Archived 7 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Los Angeles Times, 16 November 2017. Accessed 6 February 2018. Stevenson, Bryan (24 June 2017). "A Presumption of Guilt". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2020. "SHEPPARD v. MAXWELL (1966), No. 490, Argued: February 28, 1966 Decided: June 6, 1966". FindLaw's United States Supreme Court. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019. "Cognitive Bias and Its Impact on Expert Witnesses and the Court". Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019. Further reading "Prima Facie Presumptions of Guilt" (1972) 121 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 531 Fellman. "Statutory Presumptions of Guilt". The Defendant's Rights Today. University of Wisconsin Press. 1977. p 106. Martin, "The Burden of Proof as Affected by Statutory Presumptions of Guilt" (1939) 17 Canadian Bar Review 37 Roscoe, H.; Granger, T.C. (1840). A Digest of the Law of Evidence in Criminal Cases. Wharton. A Treatise on the Criminal Law of the United States. 1857. Sections 714, 727, 728 Presumption of Guilt: The Global Overuse of Pretrial Detention published by Open Society Foundations377 views -

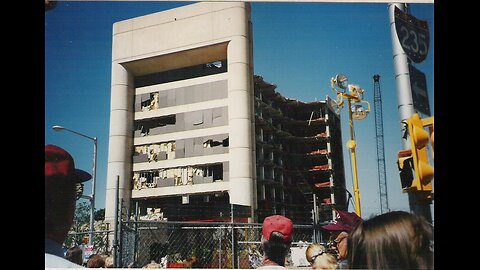

The Oklahoma City Bombing Case and Conspiracy (1999)

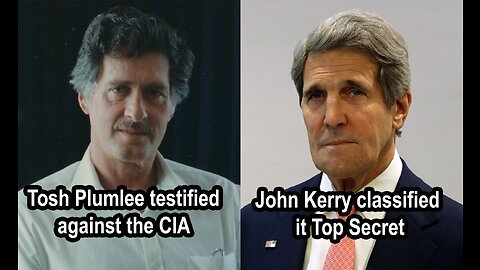

The Memory HoleAlternative theories have been proposed regarding the Oklahoma City bombing. These theories reject all, or part of, the official government report. Some of these theories focus on the possibility of additional co-conspirators that were never indicted or additional explosives planted inside the Murrah Federal building. Other theories allege that government employees and officials, including US President Bill Clinton, knew of the impending bombing and intentionally failed to act on that knowledge. Further theories allege that the bombing was perpetrated by government forces to frame and stigmatize the militia movement, which had grown following the controversial federal handlings of the Ruby Ridge and Waco incidents, and regain public support. Government investigations have been opened at various times to look into the theories. Overview Main article: Oklahoma City bombing The bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City was one of the deadliest acts of terrorism in American history. At 9:02 a.m. CST April 19, 1995, a Ryder rental truck containing more than 6,200 pounds (2,800 kg)[1] of ammonium nitrate fertilizer, nitromethane, and diesel fuel mixture was detonated in front of the north side of the nine-story Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building.[2] The attack claimed 168 lives and left over 600 people injured.[3] Shortly after the explosion, Oklahoma State Trooper Charlie Hanger stopped 26-year-old Timothy McVeigh for driving a 1977 Mercury sedan without a license plate and arrested him for that offense and for unlawfully carrying a weapon.[4] Within days, McVeigh's old army friend Terry Nichols was arrested and both men were charged with committing the bombing. Investigators determined that they were sympathizers of a militia movement and that their motive was to retaliate against the government's handling of the Waco and Ruby Ridge incidents (the bombing occurred on the second anniversary of the Waco incident). McVeigh was executed by lethal injection on June 11, 2001 while Nichols was sentenced to life in prison. Although the indictment against McVeigh and Nichols alleged that they conspired with "others unknown to the grand jury", prosecutors, and later McVeigh himself, said the bombing was solely the work of McVeigh and Nichols. In this scenario, the two obtained fertilizer and other explosive materials over a period of months and then assembled the bomb in Kansas the day prior to its detonation. After assembly, McVeigh allegedly drove the truck alone to Oklahoma City, lit the fuse, and fled in a getaway car he had parked in the area days prior. Additional conspirators Several witnesses reported seeing a second person with McVeigh around the time of the bombing, whom investigators later called "John Doe 2".[5] In 1997, the FBI arrested Michael Brescia, a member of Aryan Republican Army, who resembled an artist's rendering of John Doe 2 based on the eyewitness accounts. However, they later released him, reporting that their investigation had indicated he was not involved with the bombing.[6] One reporter for The Washington Post reflected on the fact that a John Doe 2 has never been found: "Maybe he'll (John Doe 2) be captured and convicted someday. If not, he'll remain eternally at large, the one who got away, the mystery man at the center of countless conspiracy theories. It's possible that he never lived. It's likely that he'll never die."[6] Carol Howe, an informant for the Department of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms who had infiltrated the white supremacist enclave Elohim City, Oklahoma, filed a report in January 1995 stating that Andreas Strassmeir, Elohim City's security chief, had spoken about destroying a Federal building and had visited the Murrah building with another man.[7] Two days after the bombing, Howe reminded the ATF of the earlier report and urged investigation into a possible connection to Elohim City. McVeigh is known to have telephoned Elohim City two weeks before the bombing.[8] Jane Graham, a Housing and Urban Development employee at the Murrah building who survived the bombing, later stated that in the days before the bombing she had observed multiple suspicious persons who she suspected may have been involved (such as unfamiliar persons in maintenance or military uniforms), but that her observations were ignored by authorities.[9] Graham later identified one of these men as Andreas Strassmeir of Elohim City.[10] There are several theories that McVeigh and Nichols had a possible foreign connection or co-conspirators.[11][12] This was because Terry Nichols traveled through the Philippines while Ramzi Yousef, who committed the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, was planning his Bojinka plot in Manila.[11][13] Ramzi Yousef placed the bomb used in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing inside a rented Ryder van, the same rental company used by McVeigh, indicating a possible foreign link to Al-Qaeda.[14] Other theories link McVeigh with Islamic terrorists, the Japanese government, and German neo-Nazis.[15][16] Nichols specifically alluded to other conspirators in 2006 declaration: "There are others who assisted McVeigh whose identifies are unknown to me," but Nichols also identified two "co-conspirators".[17] In addition to unknown persons, Nichols believed Andreas Strassmeir was an agent provocateur, and FBI agent Larry A. Potts was involved in the bombing plot. Nichols went on to deny any connection to terrorist groups in the Philippines. The FBI did not reply to media requests for comment on Nichols' allegation.[18] There has also been speculation that an unmatched leg found at the bombing site may have belonged to an unidentified, additional bomber.[19] It was claimed that this bomber was either in the building when the bombing occurred, or had previously been murdered, and McVeigh had left his body in the back of the Ryder truck to hide it in the explosion.[20][21] Additional explosives One theory contends there was a cover-up of the existence of additional explosives planted within the Murrah building.[22] The theory focuses on the local news channels reporting the existence of a second and third bomb within the first few hours of the explosion.[22][23][24] Theorists point to nearby seismographs that recorded two tremors from the bombing, believing it to indicate two bombs had been used.[25] Experts dispute this, stating that the first tremor was a result of the bomb, while the second tremor was due to the collapse of the building.[15][25][26][27] Conspiracy theorists say that there are several discrepancies, such as a proposed inconsistency between the observed destruction and the bomb used by McVeigh. Physicist Samuel T. Cohen, known as the primary inventor of the neutron bomb, stated in a letter to an Oklahoma politician that he did not believe a fertilizer bomb was capable of causing the destruction at the Murrah building.[28] Similarly, Air Force Brigadier General Benton K. Partin expressed an opinion that there must have been additional explosive charges inside the Murrah building.[29] US federal government involvement Murrah Building during the recovery effort Another theory alleged that President Bill Clinton had either known about the bombing in advance or had approved the bombing.[30][31] It is also believed that the bombing was done by the government to frame the militia movement or enact antiterrorism legislation while using McVeigh as a scapegoat.[15][30][31][32] Still other theories claim that McVeigh conspired with the CIA in plotting the bombing.[15][16] In a 1993 letter to his sister, published by The New York Times in 1998, McVeigh claimed that during his time at Fort Bragg he and nine others were recruited into a secret black ops team that smuggled drugs into the United States to fund covert activities and "were to work hand-in-hand with civilian police agencies to quiet anyone whom was deemed a security risk. (We would be gov't-paid assassins!)"[33] In a 2001 declaration[34] Terry Nichols, McVeigh's convicted co-conspirator, also alleged that McVeigh reported in December 1992 how he "had been recruited to carry out undercover missions"Paragraph 10 which initially involved visiting gun shows and making contact with a loose network of anti-government and far-right sympathizers. This undercover activity allegedly escalated to armed robberies and a planned bombing under the direction of FBI agent Larry A. Potts.Paragraph 33 David Paul Hammer, a convicted murderer in the same facility as McVeigh for about two years, reported that McVeigh stated similar allegations to him: that McVeigh was an "undercover operative" for the Department of Defense, and that Andreas Strassmeir was a similar operative but with "a different handler" and they had worked together in planning the bombing.[35][non-primary source needed] Middle Eastern involvement The Third Terrorist: The Middle East Connection to the Oklahoma City Bombing by journalist Jayna Davis about evidence of Oklahoma City bombing was published in April 2004 by Nelson Current Publishers, and became a New York Times best-seller. The Justice Department initially sought, but then abandoned its search for, a Middle East suspect. In contrast to conspiracy theories that the bombing was a false flag attack perpetrated by elements of the US government or white supremacists in Elohim City, the book presents a theory that links the Oklahoma City bombers to agents of Iraq and Al-Qaeda, operating under Iranian state sponsorship.[36][37] Investigations In 2006, US Congressman Dana Rohrabacher said that the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the U.S. House Committee on International Relations, which he chaired, would investigate whether the Oklahoma City bombers had assistance from foreign sources.[14] On December 28, 2006, when asked about fueling conspiracy theories with his questions and criticism, Rohrabacher told CNN: "There's nothing wrong with adding to a conspiracy theory when there might be a conspiracy, in fact."[38] Among other unresolved questions, Rohrabacher also criticized the FBI for not explaining how Nichols, who did not work steadily, paid for his several trips to the Philippines and had $20,000 cash; for not finding explosives concealed in Nichols's house until a decade after the bombing; for not explaining the "rush to rule out the existence of John Doe Number 2"; and for not thoroughly investigating possible connections between McVeigh and the Aryan Republican Army and Andreas Strassmeir.[39] In March 2007, Danny Coulson, who served as deputy assistant director of FBI at the time of attacks, voiced his concerns and called for reopening of investigation.[40] On September 28, 2009, Jesse Trentadue, a Salt Lake City attorney, released security tapes that he obtained from the FBI through the Freedom of Information Act that show the Murrah building before and after the blast from four security cameras. The tapes are blank at points before 9:02 am, the time of detonation. Trentadue said that the government's explanation for the missing footage is that the tape was being replaced at the time. Said Trentadue, "Four cameras in four different locations going blank at the same time on the morning of April 19, 1995. There ain't no such thing as a coincidence."[41][42] Trentadue became interested in the case when his brother, Kenneth Michael Trentadue, died in federal custody, during what Trentadue believes was an interrogation because Kenneth was mistaken for a possible conspirator in the Oklahoma City bombing.[43] In a civil suit, the court determined Trentadue's injuries could have been self-inflicted and rejected the Trentadue family claim that he was murdered. However, the family was awarded $1.1 million for emotional distress on the findings the Bureau of Prisons mismanaged the investigation and aftermath of Trentadue's death.[44] In November 2014, John R. Schindler, a former professor at the Naval War College and National Security Agency intelligence officer, wrote "It would be good if a serious re-look at OKBOMB’s many unanswered questions were established for the event", because of "the existence of important evidence indicating there’s something we should be talking about". He stated that when he participated in a reexamination by the United States Intelligence Community after the September 11 attacks of possible foreign involvement with recent terrorist attacks, he found "as Rohrabacher’s investigators did a few years later, that the FBI and DoJ had no interest in anyone peeking into the case, which they considered closed, indeed tightly shut. Even in Top Secret channels, avenues were blocked". While cautioning that the bombing "has attracted more than its share of charlatans and self-styled experts, some of whom are eager to pin the bombing on Arabs, Masons, Jews, and perhaps space aliens", Schindler urged a resumption of Rohrabacher's investigation and cited two issues as notable: McVeigh's and Nichols's visits to the Philippines, and the activities of a German national and friend of McVeigh.[45] See also Arlington Road List of terrorist incidents Lone wolf (terrorism) 1941 Pearl Harbor advance-knowledge conspiracy theory 1962 Operation Northwoods; 1956-1990 Operation Gladio; Operation Gladio B; etc. 1963 John F. Kennedy assassination conspiracy theories 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident 1994 AMIA bombing 1995 Oklahoma City bombing 1995 Oklahoma City bombing conspiracy theories The Third Terrorist: The Middle East Connection to the Oklahoma City Bombing, a non-fiction book Richard Snell, CSA member executed on April 19, 1995. 1999 Columbine High School Massacre 1999+ Able Danger 2001 Shijiazhuang bombings 2001/9/11 September 11 attacks 9/11 Truth movement 9/11 conspiracy theories Opinion polls about 9/11 conspiracy theories Osama bin Laden death conspiracy theories Operation Terror, a 2012 thriller film fictionalizing 9/11 2004 Madrid train bombings controversies 2005 London July bombings conspiracy theories 2011 Norway attacks 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting conspiracy theories, people who thought the school shooting was a false flag government attack False flag References Rogers, J. David; Keith D. Koper. "Some Practical Applications of Forensic Seismology" (PDF). Missouri University of Science and Technology. pp. 25–35. Retrieved March 24, 2009. Thomas, Jo (April 30, 1996). "For First Time, Woman Says McVeigh Told of Bomb Plan". The New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2009. Shariat, Sheryll; Sue Mallonee; Shelli Stephens-Stidham (December 1998). "Oklahoma City Bombing Injuries" (PDF). Injury Prevention Service, Oklahoma State Department of Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-18. Retrieved 2014-08-09. Ottley, Ted (April 14, 2005). "License Tag Snag". truTV. Archived from the original on August 29, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2009. Posner, Gerald (2013-03-09). The Third Man: Was there another bomber in Oklahoma City?. Satya ePublishing Inc. ASIN B00BRV9ORG. is the draft of a 1997 article submitted to The New Yorker about John Doe 2, and it weighs the evidence for and against another conspirator. Carlson, Peter (March 23, 1997). "In all the speculation and spin surrounding the Oklahoma City bombing, John Doe 2 has become a legend — the central figure in countless conspiracy theories that attempt to explain an incomprehensible horror. Did he ever really exist?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2009. Mark S. Hamm Crimes Committed by Terrorist Groups: Theory, Research, and Prevention. DIANE Publishing, p. 207. Hastings, Deborah (23 February 1997). "Elohim City on Extremists' Underground Railroad". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-05-13. Donald Jeffries (2016). Hidden History: An Exposé of Modern Crimes, Conspiracies, and Cover-Ups in American Politics. Skyhorse Publishing; Chapter 6: "The Clinton Years" David Hoffman (1998). The Oklahoma City Bombing and the Politics of Terror. Feral House. Krall, Jay (June 18, 2002). "Conspiracy buffs see Padilla, Oklahoma City link". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved March 24, 2009. Cosby, Rita; Clay Rawson; Peter Russo (April 17, 2005). "Did Oklahoma City Bombers Have Help?". Fox News. Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved March 25, 2009. Berger, J.M. "Did Nichols and Yousef meet?". Intelwire.com. Archived from the original on September 25, 2006. Retrieved March 25, 2009. Rohrabacher, Dana; Phaedra Dugan. "The Oklahoma City Bombing: Was There A Foreign Connection?" (PDF). Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee of the House International Relations Committee. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2009. Retrieved March 25, 2009. Knight, Peter. Conspiracy Theories in American Hisw/tory. pp. 554–555. Hamm, Mark S. Apocalypse in Oklahoma. p. 205. "Declaration of Terry Lynn Nichols" (PDF). dissentradio.com. Retrieved 2024-06-01. "Nichols says bombing was FBI op". 22 February 2007. Thomas, Jo (May 23, 1997). "McVeigh Defense Team Suggests Real Bomber Was Killed in Blast". The New York Times. Retrieved June 5, 2009. Hamm, Mark S. In Bad Company. p. 228. Hamm, Mark S. Apocalypse in Oklahoma. p. 240. Taibbi, Matt (October 24, 2006). "The Low Post: Murrah Redux". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 9, 2006. Retrieved April 5, 2009. "From KWTV: Breaking News: Oklahoma City Explosion". CNN Live. April 19, 1995. "Local Coverage: Oklahoma City Explosion". KYVTV Channel 9. April 19, 1995. Stickney, Brandon M. All-American Monster. p. 265. "Nichols' Lawyers Say Government Leaked Information to the Media". Rocky Mountain News. September 20, 1997. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2009. "Blast "Theories" Irritate Bomb Expert". The Oklahoman. September 24, 1995. Retrieved August 20, 2024. "It would have been absolutely impossible and against the laws of nature for a truck full of fertilizer and fuel oil ... no how much was used ... to bring the building down." As quoted by Gore Vidal (2002) Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace: How We Got to Be So Hated, PublicAffairs, p. 120; ellipses as in original text. "When I first saw the pictures of the truck-bomb's asymmetrical damage to the Federal building, my immediate reaction was the pattern of damage would have been technically impossible without supplementing demolition charges at some of the reinforcing concrete column bases....For a simplistic blast truck-bomb, of the size and composition reported, to be able to reach out in the order of 60 feet and collapse a reinforced column base the size of column A-7 is beyond credulity." Vidal (2002), pp. 119-120; ellipses as in original text Crothers, Lane. Rage on the Right. pp. 135–136. Hamm, Mark S. Apocalypse in Oklahoma. p. 219. Sturken, Marita. Tourists of History. p. 159. Jo Thomas (July 1, 1998) McVeigh Letters Before Blast Show the Depth of His Anger, The New York Times, accessed 21 April 2018 Declaration of Terry Lynn Nichols Archived 2018-04-21 at the Wayback Machine, Filed Feb 21, 2001 with the US District Court "Declaration of David Paul Hammer" (PDF). dissentradio.com. Staff. "Author links man arrested in Quincy to the subject of her book on Oklahoma City bombing". The Patriot Ledger, Quincy, MA. Retrieved 2021-07-27. Crogan, Jim (7 July 2005). "The Rohrabacher Test, Congressman questions Terry Nichols about Oklahoma City bombing". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on 2012-09-24. Retrieved 2012-07-04. Edwards, David; Ron Brynaert (December 28, 2006). "CNN: Is GOP Rep. 'fueling' Oklahoma City bombing conspiracy theories?". TheRawStory.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2009. "In retrospect, it is not clear if federal law enforcement expended an adequate amount of time or effort exploring the links between the Aryan bank robbers, Andreas Strassmeir and Timothy McVeigh. For nearly a year after the bombing, the FBI did not interview Strassmeir. Only when he had fled the country was he queried briefly on the phone by the FBI. The agents apparently accepted his denial of any relationship with McVeigh, and there is no evidence of any further investigation into this possible link." "Call to reopen Oklahoma bomb case". BBC News. March 2, 2007. Retrieved March 25, 2009. Nolan, Clay (September 28, 2009). "Secret footage specifies chaos minutes after the Oklahoma City Bombings". The Oklahoman. Archived from the original on September 30, 2009. Retrieved September 28, 2009. "Material missing from Okla. bombing tapes, lawyer says". USA Today. Associated Press. September 27, 2009. Retrieved September 28, 2009. Witt, Howard (2006-12-10). "To him, Murrah blast isn't solved: Lawyer investigating 1995 Oklahoma City attack says loose ends indicate likelihood of neo-Nazi connections". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2008-12-14.[dead link] Dannenberg, John E. "$1.1 Million FTCA Emotional Distress Award in BOP Suicide Death Upheld, Even Though Murder by Guards Suspected". Prison Legal News. Retrieved 3 March 2022. Schindler, John R. (2014-11-17). "Lingering OKBOMB Questions". The XX Committee. Retrieved 17 November 2014. Further reading flagOklahoma portaliconLaw portalflagUnited States portaliconPolitics portalicon1990s portal Hammer, David Paul, 2010. Deadly Secrets: Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma City Bombing. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4520-0363-4. Crothers, Lane. Rage on the Right: The American Militia Movement from Ruby Ridge to Homeland Security. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003. ISBN 0-7425-2546-5. Hamm, Mark S. Apocalypse in Oklahoma: Waco and Ruby Ridge Revenged. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1997. ISBN 1-55553-300-0. Hamm, Mark S. In Bad Company: America's Terrorist Underground. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2002. ISBN 1-55553-492-9. Israel, Peter, Jones, Stephen. Others Unknown: Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma City Bombing Conspiracy. New York: PublicAffairs, 2001. ISBN 978-1-58648-098-1. Knight, Peter. Conspiracy Theories in American History: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2003. ISBN 1-57607-812-4. Stickney, Brandon M. All-American Monster: The Unauthorized Biography of Timothy McVeigh. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1996. ISBN 1-57392-088-6. Sturken, Marita. Tourists of History: Memory, Kitsch, and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-8223-4103-4. External links Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oklahoma City bombing. Voices of Oklahoma interview with Stephen Jones. Interview with Stephen Jones, public defender for Timothy McVeigh and author of Others Unknown: The Oklahoma City Bombing Case and Conspiracy. Conducted January 27, 2010. Original audio and transcript archived with Voices of Oklahoma oral history project. vte Conspiracy theories List of conspiracy theories Overview Core topics Antiscience Cabals deep state éminence grise power behind the throne Civil / Criminal / Political conspiracies Conspiracy Crisis actors Deception Dystopia Espionage Global catastrophe scenarios Hidden message Pseudohistory Pseudoscience Secrecy Secret societies Urban legends and myths Psychology Attitude polarization Cognitive dissonance Communal reinforcement Confirmation bias Denialism Locus of control Manipulation Mass psychogenic illness moral panics Paranoia Psychological projection Astronomy and outer space 2012 phenomenon Nibiru cataclysm Ancient astronauts Apollo Moon landings Flat Earth Hollow Moon Reptilians UFOs Alien abduction Area 51 Black Knight satellite Cryptoterrestrial / Extraterrestrial / Interdimensional hypothesis Dulce Base Estimate of the Situation (1948) Lake Michigan Triangle MJ-12 Men in black Nazi UFOs Die Glocke Project Serpo Hoaxes Dundy County (1884) Maury Island (1947) Roswell (1947) Twin Falls (1947) Aztec, New Mexico (1949) Southern England (1967) Ilkley Moor (1987) Gulf Breeze (1987–88) Alien autopsy (1995) Morristown (2009) Deaths and disappearances Assassination / suicide theories Zachary Taylor (1850) Louis Le Prince (1890) Lord Kitchener (1916) Tom Thomson (1917) Władysław Sikorski (1943) Benito Mussolini (1945) Adolf Hitler (1945) Subhas Chandra Bose (1945) Johnny Stompanato (1958) Marilyn Monroe (1962) John F. Kennedy (1963) Lee Harvey Oswald (1963) Lal Bahadur Shastri (1966) Harold Holt (1967) Martin Luther King Jr. (1968) Robert F. Kennedy (1968) Salvador Allende (1973) Aldo Moro (1978) Renny Ottolina (1978) Pope John Paul I (1978) Airey Neave (1979) Olof Palme (1986) Zia-ul-Haq (1988) GEC-Marconi scientists (1980s–90s) Turgut Özal (1993) Vince Foster (1993) Kurt Cobain (1994) Yitzhak Rabin (1995) Diana, Princess of Wales (1997) Alois Estermann (1998) Nepalese royal family (2001) Yasser Arafat (2004) Benazir Bhutto (2007) Osama bin Laden (2011) Hugo Chávez (2013) Seth Rich (2016) Alejandro Castro (2018) Jeffrey Epstein (2019) Sushant Singh Rajput (2020) John McAfee (2021) Accidents / disasters Mary Celeste (1872) RMS Titanic (1912) Great Kantō earthquake (1923) Lynmouth Flood (1952) Dyatlov Pass (1959) Lost Cosmonauts (1950s–60s) JAT Flight 367 (1972) United Air Lines Flight 553 (1972) South African Airways Flight 295 (1987) Khamar-Daban (1993) MS Estonia (1994) TWA Flight 800 (1996) EgyptAir Flight 990 (1999) Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 (2014) Other cases Joan of Arc (1431) Yemenite children (1948–54) Elvis Presley (1977) Jonestown (1978) Body double hoax Paul McCartney Avril Lavigne Vladimir Putin Melania Trump Energy, environment Agenda 21 California drought manipulation Climate change denial false theories Free energy suppression HAARP Red mercury False flag allegations USS Maine (1898) RMS Lusitania (1915) Reichstag fire (1933) Pearl Harbor (1941) USS Liberty (1967) Lufthansa Flight 615 (1972) Widerøe Flight 933 (1982) KAL Flight 007 (1983) Mozambican presidential jet (1986) Pan Am Flight 103 (1988) Oklahoma City bombing (1995) 9/11 attacks (2001) advance knowledge WTC collapse Madrid train bombing (2004) London bombings (2005) Smolensk air disaster (2010) Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 (2014) Denial of the 7 October attacks (2023) Gender and sexuality Alpha / beta males Anti-LGBT anti-gender movement Chemicals drag panic gay agenda gay Nazis myth HIV/AIDS stigma United States Homintern Lavender scare Recruitment Grooming litter box hoax Transvestigation GamerGate Ideology in incel communities Larries / Gaylors Satanic panic Soy and masculinity Health 5G misinformation Anti-vaccination autism MMR Thiomersal in chiropractic misinformation Aspartame Big Pharma Chemtrails COVID-19 Ivermectin lab leak vaccines turbo cancer in Canada / Philippines / United States Ebola Electronic harassment Germ theory denialism GMOs HIV/AIDS denialism origins theories oral polio AIDS hypothesis Lepers' plot Medbeds SARS (2003) Water fluoridation Pont-Saint-Esprit mass poisoning Race, religion and/or ethnicity Bhagwa Love Trap CERN ritual hoax COVID-19 and xenophobia Freemasons French Revolution [fr] Gas chambers for Poles in Warsaw (1940s) German POWs post-WWII Priory of Sion Product labeling Halal Kosher Tartarian Empire War against Islam White genocide Antisemitic Andinia Plan Blood libel Cohen Plan Doctors' plot during the Black Death Epsilon Team George Soros Holocaust denial Trivialization International Jewish conspiracy Committee of 300 Cultural Bolshevism / Jewish Bolshevism Żydokomuna Judeo-Masonic plot The Protocols of the Elders of Zion World War II Z.O.G. Judeopolonia Killing of Jesus Kalergi Plan New World Order Rothschilds Stab-in-the-back myth Christian / Anti-Christian Anti-Catholic Jesuits Popish Plot Vatican Bible Giuseppe Siri Islamophobic Counter-jihad Bihar human sacrifice Eurabia Great Replacement Love jihad Proposed "Islamo-leftism" inquiry Trojan Horse scandal Genocide denial / Denial of mass killings Armenian Bangladesh Bosnian Cambodian The Holocaust Holodomor Nanjing Rwandan Sayfo Serbs during WWII Regional Asia India Cow vigilante violence Greater Bangladesh Pakistan Jinnahpur Philippines Tallano gold South Korea Finger-pinching conspiracy theory Thailand Finland Plot Americas (outside the United States) Argentina Andinia Plan Canada Avro Arrow cancellation Leuchter report Peru Casa Matusita Venezuela Daktari Ranch affair Golpe Azul Middle East / North Africa In the Arab world 10 agorot Cairo fire Israel-related animal theories Iran Western-backed Iranian Revolution Israel Pallywood Russia Alaska payment Dulles' Plan Golden billion Petrograd Military Organization Rasputin Ukraine bioweapons Turkey 2016 coup attempt Ergenekon Operation Sledgehammer Gezi Park protests Sèvres syndrome Üst akıl Other European Euromyth Ireland German Plot Italy Itavia Flight 870 Lithuania Statesmen Roman Republic First Catilinarian conspiracy Spain Mano Negra affair Sweden Lilla Saltsjöbadsavtalet UK Clockwork Orange plot Elm Guest House Harold Wilson Voting pencil United States Barack Obama citizenship religion parentage "Obamagate" / Spygate Biden–Ukraine Black helicopters CIA and JFK CIA assistance to bin Laden Clinton body count Cultural Marxism Election denial movement FBI secret society FEMA camps Georgia Guidestones Jade Helm 15 Montauk Project Philadelphia Experiment Pizzagate The Plan Project Azorian QAnon Pastel incidents Saddam–al-Qaeda Sandy Hook (2012) Trump–Ukraine "Vast right-wing conspiracy" Vietnam War POW/MIA issue / Stab-in-the-back myth 2020 election Italygate "Pence Card" Maricopa County ballot audit Stop the Steal Other Dead Internet theory NESARA/GESARA New Coke Phantom time / New chronology Shadow government claims Bilderberg Illuminati synarchism Shakespearean authorship Pseudolaw Admiralty law Freeman on the land movement Redemption movement Sovereign citizens Strawman theory Tax protesters Satirical Acre Bielefeld Birds Aren't Real Li's field Ted Cruz–Zodiac Killer meme See also Argument from ignorance Conspiracy Encyclopedia Conspiracy fiction Conspirituality Dogma pseudoskepticism Falsifiability Fringe science Historical negationism Online youth radicalization Paranormal Prejudice hate speech Radicalization Science by press conference Superstition Categories: Oklahoma City bombingConspiracy theories in the United StatesPseudohistoryDeath conspiracy theories536 views